Netflix has agreed to compensate Comcast in return for assurances that the cable company’s subscribers would no longer be caught in the middle of a dispute between Comcast and one of Netflix’s content distributors.

Netflix has agreed to compensate Comcast in return for assurances that the cable company’s subscribers would no longer be caught in the middle of a dispute between Comcast and one of Netflix’s content distributors.

The multi-year agreement between the two companies will bring Netflix direct access to Comcast’s broadband network with a Service Level Agreement that will guarantee streaming stability for customers who have loudly complained about Netflix’s deteriorating performance.

The controversial arrangement has probably established a precedent for other large Internet Service Providers likely to seek compensation to handle Netflix traffic. As of this evening, both AT&T and Verizon have already acknowledged they are negotiating with Netflix for similar arrangements.

Caught in the middle of the dispute are Comcast customers paying for a reliable Internet connection and getting slowing connections and re-buffering problems while attempting to watch Netflix content during peak usage times.

One side accuses Comcast of violating Net Neutrality while the other blames Netflix for dumping enormous Internet traffic on Internet Service Providers without compensation for network upgrades. Also in the crossfire is Cogent, a third-party company delivering Netflix content to Comcast’s front door.

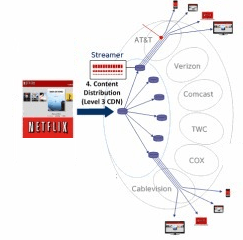

How Netflix Distributes Its Streaming Movies and TV Shows

Netflix has traditionally avoided owning the “pipes” that distribute movies and TV shows to paying customers. Instead, it usually contracts with “transit providers” to send content from Netflix headquarters on to “content distribution networks (CDN)” that manage video streaming. A Netflix video may pass through a number of connections on a variety of independently owned networks before it arrives at the front door of your Internet Service Provider. Companies like Comcast handle “the last mile” of the journey that began at Netflix and ends at your computer or television set.

Netflix has traditionally avoided owning the “pipes” that distribute movies and TV shows to paying customers. Instead, it usually contracts with “transit providers” to send content from Netflix headquarters on to “content distribution networks (CDN)” that manage video streaming. A Netflix video may pass through a number of connections on a variety of independently owned networks before it arrives at the front door of your Internet Service Provider. Companies like Comcast handle “the last mile” of the journey that began at Netflix and ends at your computer or television set.

Netflix does not rely on just one transit provider to handle its traffic. Level 3, Cogent, and XO Communications all reportedly serve in that capacity, depending on where traffic is headed. The same is true for the CDN’s Netflix contracts with to regionally stream content to each subscriber.

Netflix determines how to handle your streaming movie request behind the scenes, selecting a CDN that is close to you and capable of delivering the most stable streaming experience at that moment. If you are a Comcast or Verizon customer, Netflix often selects Cogent to handle its content. Cogent is also well known for its relatively low cost.

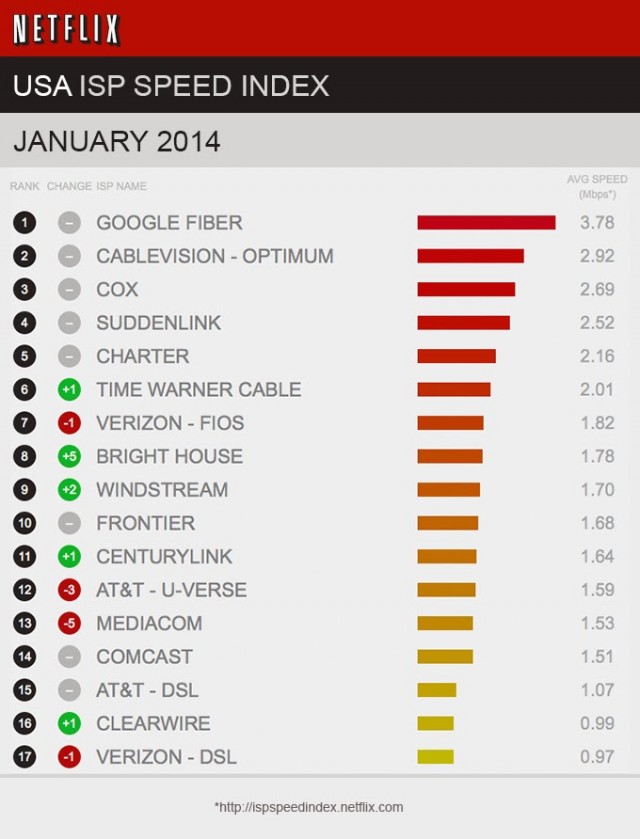

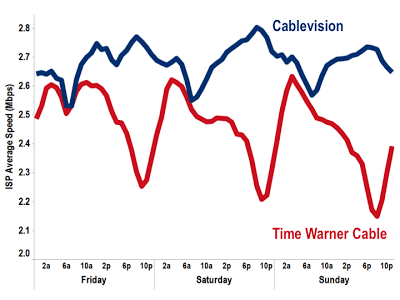

If you are served by Cablevision, Frontier, or certain other providers like Google Fiber, Netflix will instead direct your streaming request to a CDN located within your provider’s own network. These “Open Connect” boxes store Netflix content in a type of cache and can stream it to customers directly without sending video packets across multiple third-party networks. Theoretically, Open Connect offers an efficient and stable way of distributing Netflix content to customers. It also saves Netflix money and in return, it costs the ISP nothing — Netflix pays for the equipment and service.

Cogent vs. Big Telecom

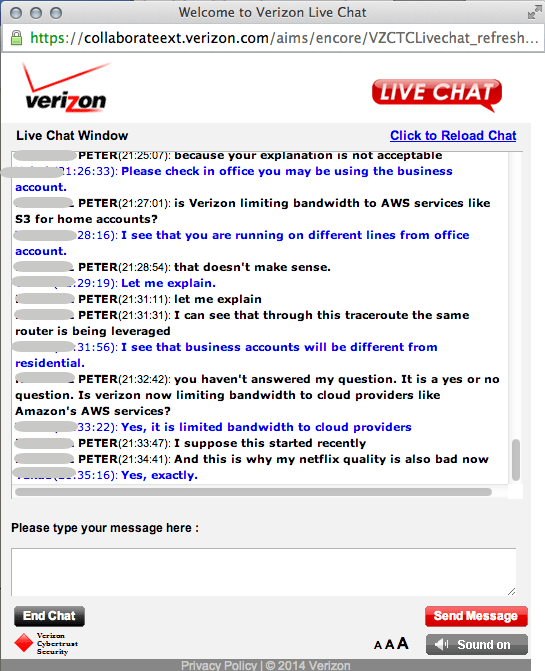

Netflix and YouTube together are now estimated to cover 50 percent of all video traffic on the Internet, and that traffic is growing. Cogent dutifully passes that video content along to Internet Service Providers like Verizon and Comcast that have customers waiting to watch. But it is a two-way street. Any outbound traffic from customers could also be forwarded to Cogent to send on. Traditionally, both sides have managed the traffic by gradually increasing the bandwidth and speed of their connections to one-another. But as Netflix traffic grows and grows, companies like Comcast and Verizon believe they are being saddled with the costs to upgrade their networks in ways that are out of proportion to the traffic they send in the other direction. ISPs often grumble about the cost but keep on upgrading to keep paying customers happy. Verizon and Comcast are suspected of dragging their feet on those upgrades in an effort to win compensation.

Netflix and YouTube together are now estimated to cover 50 percent of all video traffic on the Internet, and that traffic is growing. Cogent dutifully passes that video content along to Internet Service Providers like Verizon and Comcast that have customers waiting to watch. But it is a two-way street. Any outbound traffic from customers could also be forwarded to Cogent to send on. Traditionally, both sides have managed the traffic by gradually increasing the bandwidth and speed of their connections to one-another. But as Netflix traffic grows and grows, companies like Comcast and Verizon believe they are being saddled with the costs to upgrade their networks in ways that are out of proportion to the traffic they send in the other direction. ISPs often grumble about the cost but keep on upgrading to keep paying customers happy. Verizon and Comcast are suspected of dragging their feet on those upgrades in an effort to win compensation.

Verizon and Comcast argue they should be paid by content producers responsible for generating tons of Internet traffic to help cover the cost of upgrades. Instead, Netflix offered its Open Connect boxes, which keep Netflix traffic within an ISPs own network, reducing the necessity of constantly upgrading connections with other transit providers. Verizon and Comcast don’t want Netflix’s solution — they want cold hard cash.

Conflict of Interest

Some network engineers cannot understand all the controversy about Comcast’s arrangement with Netflix. Some believe Netflix is simply shifting traffic away from third-party Cogent to Comcast directly, presumably at a cost savings. They suggest customers will be happy that streaming quality is restored and Netflix also wins a guaranteed level of performance they never had with Cogent.

But that argument does not explain why Netflix was compelled to make a financial arrangement with Comcast. The two companies have been in negotiations on the subject of traffic compensation for months. Many industry observers believe those talks went nowhere until Netflix customers began complaining about the increasing network slowdowns. Some even dropped their Netflix subscriptions over the issue.

But that argument does not explain why Netflix was compelled to make a financial arrangement with Comcast. The two companies have been in negotiations on the subject of traffic compensation for months. Many industry observers believe those talks went nowhere until Netflix customers began complaining about the increasing network slowdowns. Some even dropped their Netflix subscriptions over the issue.

Netflix CEO Reed Hastings admitted he made a deal with Comcast to restore customer confidence in Netflix and end subscriber frustration. It was also increasingly clear Comcast was in no hurry to improve things on its own, despite the fact its own customers were the ones most directly affected.

So why wouldn’t Comcast (or Verizon or Time Warner Cable) take Netflix up on its offer of free Open Connect boxes that would reasonably solve streaming problems without forcing anyone to spend a fortune on upgrades? Simply put, all three companies are direct competitors of Netflix. Helping Netflix offer a top quality streaming experience is not in the best interests of Comcast (or others) that are facing potential cord-cutting customer losses in their subscription video businesses. Verizon has partnered with Redbox to deliver streamed video, Comcast operates Streampix, its own online streaming service, and Time Warner Cable offers a variety of on-demand and streamed video content for its cable TV subscribers. None of these services have suffered from traffic congestion issues.

ISP Payday

What About Net Neutrality? What About Paying Customers?

With Net Neutrality tossed out by the courts, there is little any regulator can do to resolve disputes until Net Neutrality can be properly enforced under a stronger regulatory framework. Some argue the congestion issues creating the problems with Netflix are not a true violation of Net Neutrality in any event because providers are not artificially prioritizing traffic.

They are simply not keeping up with upgrades that just so happen to directly impact a competitor while leaving their own services unscathed.

Providers also seem characteristically unconcerned about complaining customers, passing blame for the problem on to Netflix. Besides, they remind you, paying for an Internet connection alone does not entitle you to any guarantee of performance.

The Dam Breaks

With this week’s agreement between Comcast and Netflix, both AT&T and Verizon wasted no time admitting they are both seeking compensation from Netflix as well. Other providers are likely to follow.

Netflix warned investors that paid agreements with ISPs could adversely affect its earnings due to increased costs. Although stopping short of suggesting price increases for Netflix customers could come as a result, Wall Street wasted no time worrying about the financial impact of deals like the one between Netflix and Comcast.

The Wall Street Journal reported the momentum appears to be shifting in favor of large Internet providers like Comcast and AT&T and away from content producers.

Janney Capital analyst Tony Wible suggested Comcast’s toll booth could create a barrier for other content producers if the cable company asks for significant compensation.

“Although there is no prioritization benefit [from the deal], we suspect that the exchange of money for resolution/performance could (if large) effectively limit competition,” said Wible. “In essence, Netflix could be trading [profit] margins for subscribers. Few others can match Netflix’s [spending budget to acquire content] without incurring massive losses. The competition may now have to cope with additional fees that sway their willingness to compete if they do not already have a large subscriber base.”

In other words, a new Internet startup could face hard questions from investors about how it intends to cover ISP demands for compensation in return for a suitable connection to reach customers. A large venture like Netflix has enough resources to handle those costs and negotiate for a better deal while a smaller startup may not.

[flv]http://www.phillipdampier.com/video/WSJ Netflix Comcast Agreement 2-24-14.flv[/flv]

Netflix has signed a deal with Comcast to ensure smooth streaming, in what is being called a landmark agreement. Wall Street Journal reporter Shalini Ramachandran explains the agreement. (3:39)

Subscribe

Subscribe

Few were surprised more by the sudden announcement that Comcast was seeking to acquire Time Warner Cable all by itself than the negotiating team from Charter Communications.

Few were surprised more by the sudden announcement that Comcast was seeking to acquire Time Warner Cable all by itself than the negotiating team from Charter Communications. According to Bloomberg News, the

According to Bloomberg News, the

Malone called today’s divided industry “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs” and insisted on a new major consolidation wave to enhance “value creation” and deliver some major blows to satellite and telephone company competitors.

Malone called today’s divided industry “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs” and insisted on a new major consolidation wave to enhance “value creation” and deliver some major blows to satellite and telephone company competitors.

Media ownership laws were relaxed,

Media ownership laws were relaxed,