Alphabet, the parent company of Google Fiber, has lost interest in expanding its fiber to the home service and is showing signs of pulling the plug on its cable television alternative while it drags its feet on keeping promised rollout commitments.

Alphabet, the parent company of Google Fiber, has lost interest in expanding its fiber to the home service and is showing signs of pulling the plug on its cable television alternative while it drags its feet on keeping promised rollout commitments.

The first sign of trouble for the upstart fiber network came as early as 2015, when without warning Google co-founder Larry Page suddenly unveiled Alphabet, a new holding company that would be at the heart of Google and its many ventures, including Google Fiber. The concept was tailor-made to please Wall Street and investors, because it would better expose which Google projects were earning money and which were hemorrhaging cash with no sign of profitability. But an equally important event occurred in May with the hiring of Ruth Porat, who would become Alphabet’s chief financial officer.

Known inside by some at Google as “Ruthless Ruth,” Porat is Wall Street’s definition of a proper executive that keeps shareholder interests first in mind. Porat lead Morgan Stanley’s technology banking division at the heart of the first dot.com boom in the late 1990s, served as an adviser to the Treasury Department on the taxpayer bailouts of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, and was chief financial officer at Morgan Stanley by 2010. Her mission at Google: put an end to expensive innovation for innovation’s sake. If a project did not show signs of making money for shareholders, it would face intense scrutiny under her watch.

“She’s a hatchet man,” a former senior Alphabet executive frankly told Bloomberg News.

Porat

Her key priorities are “discipline” and “focus,” something Google never had to be concerned with while earning truckloads of ad-click cash. Google’s reputation for cool innovation and free services earned the company a lot of goodwill with the public, but that left money on the table for investors who want the company to step up shareholder value. Google’s founders Sergey Brin and Larry Page had enjoyed a long run innovating and announcing new projects, including scanning every printed book on the planet, giving away e-mail and office apps, and laying fiber optic cables to deliver the kind of internet service big phone and cable companies were not delivering. The company also acquired other innovators, including Nest Labs — which made connected thermostats and Webpass, which provides wireless high-speed internet access.

But for all of its success, Google also had several high-profile failures that cost billions, setting the stage for future project accountability.

One of the biggest failures was its Google Glass wearable tech project. The first edition, dubbed Explorer, was a flop and received terrible reviews. But the device also clashed with a country increasingly preoccupied with personal privacy. Not everyone appreciated Google Glass’ always-watching camera pointing in their direction, and some wearing the device were derided as “glassholes.”

“I was a Google Glass Explorer, and the experience was horrible from the start. Google Glass now sits in my office museum of failed products,” said Tim Bajarin, President of Creative Strategies Inc. in this post at re/code. “The UI was terrible, the connection unreliable and the info it delivered had little use to me. It was the worst $1,500 I have ever spent in my life. On the other hand, as a researcher, it was a great tool to help me understand what not to do when creating a product for the consumer.”

Google Glass: a major misstep

Google’s other experiments weren’t exactly pulling in a lot of money either. The company’s vision of driver-less cars met the reality of real world driving conditions (some accidents were the result) and traffic planning and safety regulators were cautious about giving a green light to the concept on American streets and highways. A long-time favorite project of Brin and Page, Project Loon — sending 100,000 balloons, blimps, and/or drones into the sky to deliver internet access is still seen by conventional wisdom as weird. These and other experimental projects lost $3.6 billion of Google’s revenue in 2016, almost twice as much as they lost the company in 2014.

After “Ruthless Ruth” entered the picture, as Bloomberg News documented, it appeared the open door to the experiment lab was closed and an exodus of project leaders and engineers began:

Six months after Teller’s rousing speech, Loon’s Mike Cassidy stepped down as project leader. Around the same time, Urmson, the self-driving car engineer, left Alphabet, as did David Vos, the head of X’s drone effort, Project Wing. Vos’s top deputy, Sean Mullaney, left the company as well. Other recent departures: Craig Barratt, chief executive officer of Access, its telecom division; Bill Maris, the CEO of its venture capital arm, GV; and Tony Fadell, the CEO of smart-thermostat company Nest, who was also working on a reboot of Google Glass. That project, now called Aura, also lost its leads of user design and engineering.

Barratt: The former head of Google Access.

The bean counters also arrived at Google Access — the division responsible for Google Fiber — and by October 2016, Google simultaneously announced it was putting a hold on further expansion of Google Fiber and its CEO, Craig Barratt, was leaving the company. About 10% of employees in the division involuntarily left with him. Insufficiently satisfied with those cutbacks, additional measures were announced in April 2017 including the departure of Milo Medin, a vice president at Google Access and Dennis Kish, a wireless infrastructure veteran who was president of Google Fiber. Nearly 600 Google Access employees were also reassigned to other divisions. Medin was a Google Fiber evangelist in Washington, and often spoke about the impact Google’s fiber project would have on broadband competition and the digital economy.

Porat’s philosophy had a sweeping impact on Alphabet and its various divisions. The most visionary/experimental projects that were originally green-lit with no expectation of making money for a decade or more now required a plan to prove profitability in five years or less. Wall Street was delighted and Alphabet’s stock was up 35% since “Ruthless Ruth” arrived, winning praise for remaking Alphabet/Google into a conventional American corporation using familiar corporate principles.

But Alphabet’s transition seems to break a promise Google co-founders Brin and Page made when Google became a public company in 2004.

“We do not intend to become one.”

Both men promised Google would never focus on short-term profitability and would encourage employees to devote 20% of their working hours on exactly the kinds of innovative projects and product developments Porat was intent on cutting or killing. Porat even has a willing army of helpers — executives were paid bonuses to kill their projects before expenses got out of hand. This helped halt development of Tableau, a project to create enormous size TV screens originally championed by Brin.

Porat also had a major hand in slashing the budget at Google’s Nest Labs division. Google spent $3.2 billion acquiring the home thermostat and smoke alarm company in 2014. Nest CEO Tony Fadell came along as part of the deal and was initially considered a major asset, having been the former Apple engineer who built the original iPod prototype. But Fadell clashed with Google’s culture and reports surfaced he was a tyrannical boss comparable to Steve Jobs at his nastiest. Google executives expected more products out of the Nest division, and didn’t get them. Fadell blamed employees and ruthless budget cuts that broke Google’s commitment to allow Nest to lose up to $500 million annually for the first five years under Google’s ownership. Even when Nest managed to generated $340 million in revenue in 2015, Porat wasn’t pleased. The higher-ups expected more considering the amount of money Google spent buying Nest Labs.

Porat also had a major hand in slashing the budget at Google’s Nest Labs division. Google spent $3.2 billion acquiring the home thermostat and smoke alarm company in 2014. Nest CEO Tony Fadell came along as part of the deal and was initially considered a major asset, having been the former Apple engineer who built the original iPod prototype. But Fadell clashed with Google’s culture and reports surfaced he was a tyrannical boss comparable to Steve Jobs at his nastiest. Google executives expected more products out of the Nest division, and didn’t get them. Fadell blamed employees and ruthless budget cuts that broke Google’s commitment to allow Nest to lose up to $500 million annually for the first five years under Google’s ownership. Even when Nest managed to generated $340 million in revenue in 2015, Porat wasn’t pleased. The higher-ups expected more considering the amount of money Google spent buying Nest Labs.

Google Fiber was launched knowing it would take billions of dollars and years to pay off for Google. Laying fiber optic cable is expensive, time-consuming, and frequently bureaucratic. Google projects that still have support from Brin and Page are usually protected from Porat’s red pencil, but if either’s optimism waivers, Porat is likely to start cutting.

By the time Barratt tried to jump-start excitement for the slowly progressing fiber service by announcing a series of new launch cities, Page appeared to have lost interest. Former employees say Page became frustrated with Google Fiber’s lack of progress.

“Larry just thought it wasn’t game-changing enough,” says a former Page adviser. “There’s no flying-saucer shit in laying fiber.”

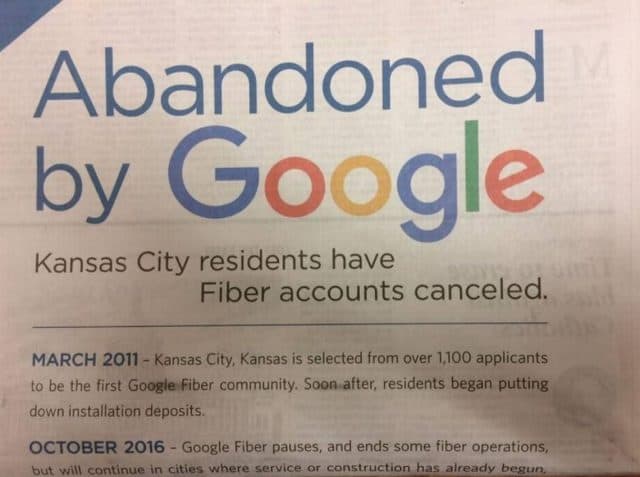

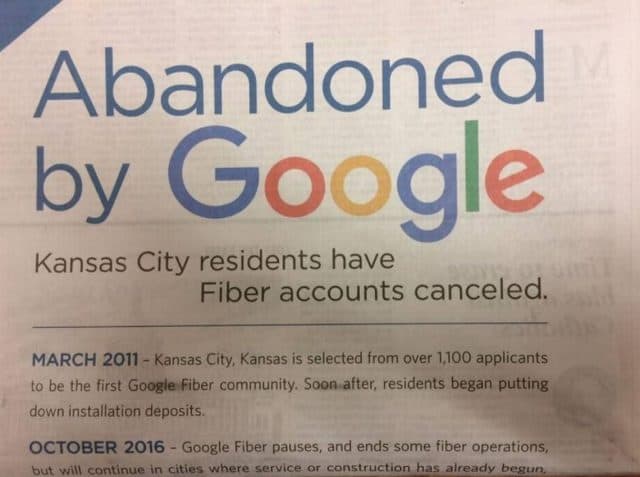

Charter Communications took out newspaper ads trumpeting Google’s abandonment of some of its potential fiber customers in Kansas City.

Left unprotected, Porat’s budget cutters invaded and further fiber expansion has been suspended, except in areas where Google was already committed to provide the service. But the cutbacks have been so significant, cities are now complaining Google is dragging its feet on its commitments.

In Kansas City — the first to get Google Fiber, the network remains incomplete. In March 2017, Google signaled it was likely to remain incomplete indefinitely after returning hundreds of $10 deposits — many paid years earlier — to residents who were informed Google Fiber would no longer expand into their neighborhoods. In the last two years, Google has become very conservative about the neighborhoods where it will expand service. In most cases, the company now targets multi-dwelling units like condos and apartments, which are cheaper to serve than single family homes.

In late September, Atlanta noticed Google Fiber was stalled in the city and nearby Sandy Springs and Brookhaven. A clear sign Google had effectively suspended construction was a sudden end to construction permit applications around six months ago. Google Fiber denies it is pulling out, but city officials notice work progress has slowed to a crawl.

“Google Fiber is currently available in over 100 residential buildings in the metro Atlanta area and in several neighborhoods in the center of the city. We’re working hard to connect as many people as possible, and encourage people to sign up for updates on our website,” a Google Fiber spokesperson said.

There have been similar problems with Google Fiber expansion in several Texas cities. Some neighborhood residents complained about shoddy installation work because of poor quality third-party contractors, and expansion has slowed down markedly in many areas.

Ironically, AT&T may have been responsible for helping kill Page’s enthusiasm for Google Fiber, serving as a regular obstacle to Google Fiber’s expansion in states like Tennessee where it has been delayed by bureaucratic pole attachment disputes, some resulting in legal action. For Ma Bell and its progeny, a five-year delay is nothing for a company that has been around since the early 1900s and took decades to build out its original telephone network.

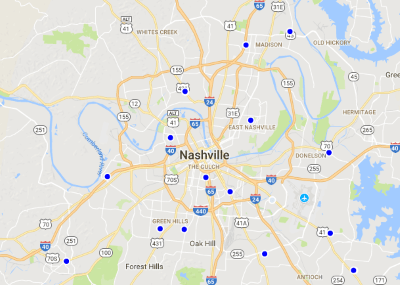

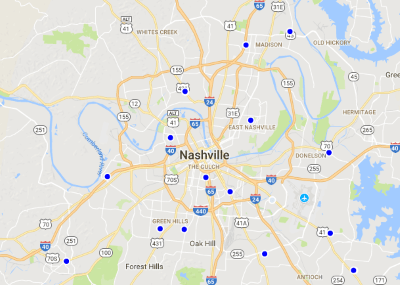

Google Fiber Huts – Nashville, Tenn.

Utilities employ a small army of workers that do nothing but deal in a world of tariffs, permit applications, and various filings to regulatory bodies that still govern parts of their operations. For a dot.com company in a hurry, filing permit applications, negotiating pole attachment agreements, hiring subcontractors that can meet regulated specifications, and dealing with incomplete or inaccurate infrastructure maps could be hell on earth. But for phone and cable companies, it is just another day on the job, and their “concern trolling” over the danger of allowing a neophyte like Google to mess with existing electric, phone, and cable wiring to make room for fiber did give some local officials pause.

Page’s hurry to accomplish his fiber dreams were effectively dashed by AT&T’s very close relationship with local officials and its ability to generate a mountain of regulatory and legal paperwork. As a result, Google admitted with great frustration that in Nashville, after months of work, it had only upgraded 33 telephone poles out of 88,000 in the city. The delay also took its toll on a Nashville-based subcontractor helping to build out Google Fiber in the city. Phoenix of Tennessee declared Chapter 11 bankruptcy in September with liabilities between $1-10 million. It also laid off 70 employees. The reason? Google Fiber is stalled in the city.

One Alphabet employee mischaracterized the end effect of the dispute in comments to the Wall Street Journal last year, “Everyone who has done fiber to the home has given up because it costs way too much money and takes way too much time.”

Christopher Mitchell, director of the Community Broadband Project summarized the situation more succinctly for Gizmodo: “the new guy gets screwed.”

Yet it would be more accurate to say companies with short attention spans and an evolving commitment away from innovation and towards Wall Street and its fixation on short-term results will have more difficulty than other companies and communities that have successfully built fiber networks with a patient focus on the future.

Porat has been defending Alphabet’s increasingly conservative spending plans and pull-backs.

Porat has been defending Alphabet’s increasingly conservative spending plans and pull-backs.

“As we reach for moonshots,” she told investors on a financial results conference call, “it’s inevitable that there will be course corrections along the way.” She called some of the shifting priorities and cutbacks “taking a pause” in some areas of business to “lay the foundation for a stronger future.”

For Google Fiber, that is coming in a number of different directions.

The company this week announced it is pulling back on offering cable television service in its new markets, including Louisville, Ky., and San Antonio, Tex., and is raising rates $20-30 a month for bundled customers in areas where television service is still being sold.

“The cost of providing TV programming continues to rise,” the company said in an email notifying customers of the rate increase. The price change will hit existing customers paying $130 a month for Fiber 1000Mbps service + TV. Current customers will pay $150 a month going forward. New customers will pay $10 more for the bundle – $160 a month.

“We’re not afraid to try new things as part of our normal way of doing business, focused on the end goal of getting superfast internet into people’s homes,” wrote head of sales and marketing for Google Access Cathy Fogler in a blog post.

Google Fiber has been a minor player in the cable television business, according to analysts, attracting around 54,000 customers nationwide as of December — only 24,000 more than it had in 2014.

As for the future, with Porat in charge of finances, it is likely Google will downscale expectations and rely on its acquisition of Webpass for future expansion, providing high-speed wireless internet to multi-dwelling apartments, condos, and businesses in dense urban areas. That eliminates costly fiber expansion to individual homes or businesses and is much less expensive to install and maintain.

Any plans for a major Google Fiber push in the future seems unlikely, considering Wall Street’s demands for Return On Investment are not easily tempered. That leaves independent local overbuilders with established ties to their communities the most likely to pick up where Google Fiber has left off. But even those are in short supply. Like any major project of this scope, the best option for getting fiber optics in your community, assuming the local cable or phone company isn’t doing it already, is to treat it as a public infrastructure project like water, sewer, roads or sidewalks.

Most cities were all too happy to compete for Google’s attention (and infrastructure investment). But now that is no longer likely, and many communities will have to decide for themselves which side of the digital divide they want to live in — the side without 21st century broadband or the side that has elected to control their own broadband future and not wait for someone else to get the job done.

Subscribe

Subscribe

Alphabet, the parent company of Google Fiber, has lost interest in expanding its fiber to the home service and is showing signs of pulling the plug on its cable television alternative while it drags its feet on keeping promised rollout commitments.

Alphabet, the parent company of Google Fiber, has lost interest in expanding its fiber to the home service and is showing signs of pulling the plug on its cable television alternative while it drags its feet on keeping promised rollout commitments.

Porat also had a major hand in slashing the budget at Google’s Nest Labs division. Google spent $3.2 billion acquiring the home thermostat and smoke alarm company in 2014. Nest CEO Tony Fadell came along as part of the deal and was initially considered a major asset, having been the former Apple engineer who built the original iPod prototype. But Fadell clashed with Google’s culture and

Porat also had a major hand in slashing the budget at Google’s Nest Labs division. Google spent $3.2 billion acquiring the home thermostat and smoke alarm company in 2014. Nest CEO Tony Fadell came along as part of the deal and was initially considered a major asset, having been the former Apple engineer who built the original iPod prototype. But Fadell clashed with Google’s culture and

Porat has been defending Alphabet’s increasingly conservative spending plans and pull-backs.

Porat has been defending Alphabet’s increasingly conservative spending plans and pull-backs.