CenturyLink is seeking “greater flexibility” to set its own prices, terms and conditions of service without a review by Washington State regulators, even as its broadband customers complain about bait and switch Internet speeds and poor service.

CenturyLink is seeking “greater flexibility” to set its own prices, terms and conditions of service without a review by Washington State regulators, even as its broadband customers complain about bait and switch Internet speeds and poor service.

Three years after the Monroe, La., based independent phone company purchased Qwest — a former Baby Bell serving the Pacific Northwest — CenturyLink continues to lose customers to cell phone providers and cable phone and broadband service. Since 2001, CenturyLink and its predecessor have said goodbye to 60 percent of their customers, reducing the number of lines in service from around 2.7 million to just over 1 million.

CenturyLink is apparently ready to lose still more after upsetting customers with a notice it intended to seek deregulation that could lead to rising phone bills.

Docket UT-130477, filed with the Washington Utilities and Transportation Commission (WUTC) proposes to replace currently regulated service with what CenturyLink calls “an Alternate Form Of Regulation.” (AFOR)

If approved, CenturyLink will “normalize” telephone rates in Washington State, language some suspect is “code” for a rate increase. For CenturyLink customers in cities like Seattle, Spokane, and Tacoma, the maximum rate permitted for basic phone service for the next three years will be $15.50 (unless a customer already pays more), before calling features, taxes, and surcharges are applied. Most observers, including the state regulator, suspect CenturyLink will limit rate hikes to $1-2 if approved. A higher increase might provoke more customers to leave.

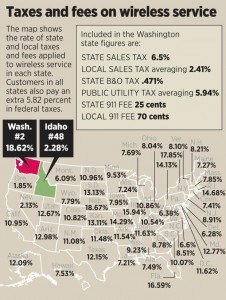

Washington residents already pay the nation’s second highest taxes on wireless service. Now landline customers also pay more. (Graphic: The Spokesman)

“We don’t think they can do much because, in our view, all (a big rate increase) is going to do is accelerate people dropping the landline into their homes,” Brian Thomas, a spokesman for the Washington Utilities and Transportation Commission told The Spokesman-Review. “A lot of people are cutting the cord.”

Frontier Communications, which previously won its own case for deregulation within its service areas including Everett, Wenatchee, and Tri-Cities, raised rates about $1 beginning this month.

A spokesman for the company confessed Frontier’s phone service is becoming obsolete.

“It’s safe to say plain old telephone service is in the process of becoming archaic for some people,” Frontier’s Carl Gipson said. “Five years from now, it will be almost – but not quite – extinct.”

Every rate change seems to provoke a review of whether landline service is still necessary.

Earlier this year, CenturyLink jumped on board legislation that purposely increased phone rates by several dollars a month by removing the sales tax exemption on residential telephone service. Wireless companies did not enjoy the same exemption and sued for parity.

A confidential settlement with state regulators made Washington phone customers, instead of telecom companies, liable for the sales tax starting in August. As a result, some residential phone bills went up at much as $5 based on retroactively charged sales tax.

Customers sticking with CenturyLink often say it is the only broadband provider in rural towns across the state. Although better than satellite broadband, the lack of regulatory oversight and technology investments have allowed CenturyLink to sell Internet speeds it cannot provide to customers.

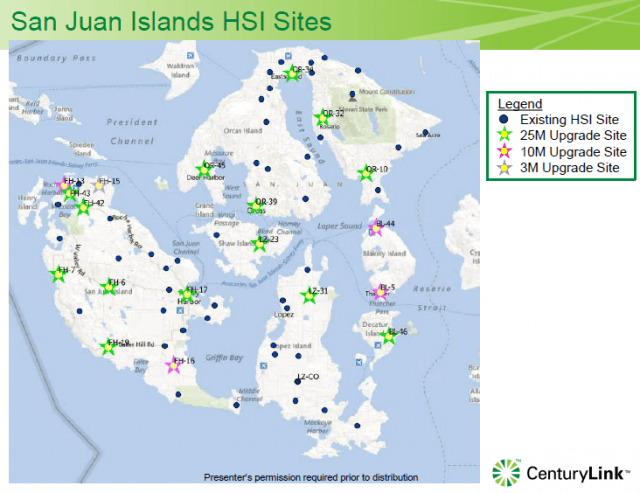

At a hearing held this week by the San Juan County Council, members criticized CenturyLink officials on hand for selling fast service but delivering slow speeds to the group of islands between the mainland of Washington State and Vancouver Island, B.C.

Hughes

“Last night I did a speed test at my house and I am paying for 10Mbps but only getting 4.74Mbps,” complained Councilman Rick Hughes (District 4 – Orcas West). “I am paying for 10 and I am only getting 5Mbps, so how is that fair? There has been a ton of frustration over the last two years we have worked on this broadband issue. Everywhere I go and every meeting I talk to all I hear is complaints about CenturyLink. No matter what they are paying for, it’s a poor broadband connection to the end customer.”

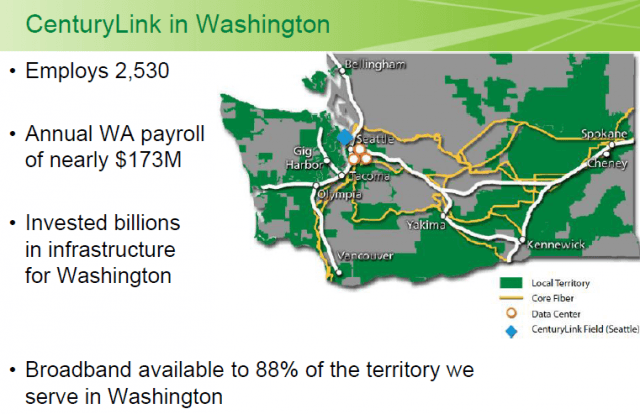

CenturyLink provides broadband to 88% of the territory the company serves in Washington. Like most telephone companies, CenturyLink relies on DSL in much of its footprint and has upgraded central offices, remote equipment, and the telephone lines that connect them. On the San Juan Islands, most customers used to receive 1-3Mbps, but CenturyLink claimed at this week’s hearing it spent billion on infrastructure improvements that can now deliver faster Internet service across the state. In San Juan County, CenturyLink claims:

- 58% of all qualified addresses were upgraded to 10-25Mbps;

- 66% now qualify for more than 10Mbps (but less than 25Mbps) versus 46% prior to upgrades;

- 29% of customers now qualify to sign up for 25Mbps service.

CenturyLink warned the council its speed claims were not to be taken literally, noting DSL “speed is dependent on distance from equipment; speeds drop quickly as distance increases.”

Hughes told CenturyLink officials residents appreciated the investment, but customers were still disappointed after being promised higher speeds than actually received.

“When people call customer service, there is always an excuse about why there is a problem,” said Hughes. “If people are paying for something, they want to receive it.”

“For our long-term financial interests in this county, we need to have reliable 10-25Mbps service to customers on any part of the islands,” Hughes added. “My goal has always been 90+ percent should be able to get 25Mbps or better connectivity in the county.”

“For our long-term financial interests in this county, we need to have reliable 10-25Mbps service to customers on any part of the islands,” Hughes added. “My goal has always been 90+ percent should be able to get 25Mbps or better connectivity in the county.”

The problem for CenturyLink is the amount of upgrade investment versus the amount of return that investment will generate. San Juan County is disconnected from the mainland and collectively house only 15,769 residents. But it is also the smallest of Washington’s 39 counties in land area, which can make infrastructure projects less costly.

CenturyLink committed to continue investment in its network “where economically feasible.”

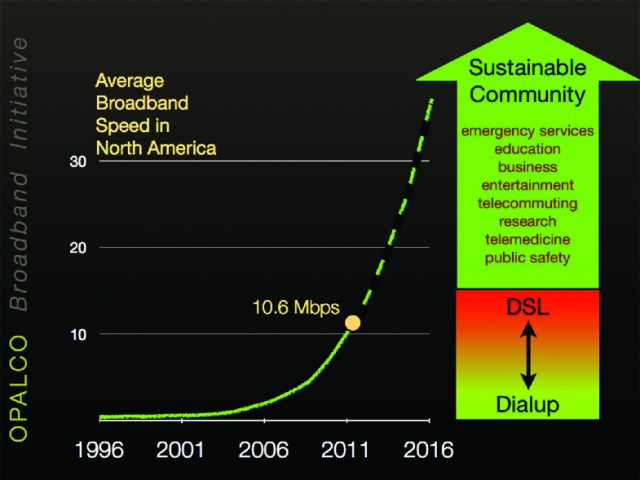

San Juan County’s Orcas Power & Light Cooperative (OPALCO), a member-owned, non-profit cooperative electric utility may have a partial solution to the problem of meeting Return on Investment requirements.

OPALCO originally proposed a hybrid fiber-wireless system designed to reach 90% of the county with a $34 million investment, to be built over two years. When completed, all county residents would pay a $15 monthly co-op infrastructure fee and a $75 monthly fee for broadband and telephone service. To gauge interest, OPALCO asked residents for a $90 pre-commitment deposit. By the annual meeting in May, the co-op admitted only 900 residents signed up and it needed 5,800 customers to make the project a success.

OPALCO originally proposed a hybrid fiber-wireless system designed to reach 90% of the county with a $34 million investment, to be built over two years. When completed, all county residents would pay a $15 monthly co-op infrastructure fee and a $75 monthly fee for broadband and telephone service. To gauge interest, OPALCO asked residents for a $90 pre-commitment deposit. By the annual meeting in May, the co-op admitted only 900 residents signed up and it needed 5,800 customers to make the project a success.

Some residents balked at the high cost, others did not want wireless broadband technology, and some local environmental activists wanted OPALCO to focus on clean, affordable energy and avoid the competitive broadband business.

The lack of commitment forced the co-op to modify its broadband plans, offering a “New Direction” to residents in June 2013.

OPALCO elected to stay out of the ISP business and instead announced a public-private initiative, providing fiber infrastructure to existing service providers. In effect, the co-op will cover the cost of building fiber extensions where CenturyLink is not willing to invest. For a $3-5 million investment from the co-op, ISPs like CenturyLink will be able to commission OPALCO to build fiber in the right places to make DSL service better. CenturyLink would have non-exclusive rights to the fiber network and would have to pay the co-op a service lease fee.

Unlike ISPs in other communities that have shunned publicly funded fiber infrastructure, CenturyLink says it will contemplate a trial — buying bandwidth from OPALCO instead of enhancing its own fiber middle mile network — to test what level of improved service CenturyLink can offer customers.

Regardless of CenturyLink’s plans, OPALCO is moving forward installing limited fiber connections as part of an effort to develop a more modern electric grid.

“Our data communications network brings exponential benefit to our membership,” OPALCO notes. “It includes tools that allow the co-op to: control peak usage and keep power costs down, remotely manage and control the electrical distribution system, manage and resolve power outages more efficiently, integrate and manage community solar projects and improve public safety throughout the county.”

“Our data communications network brings exponential benefit to our membership,” OPALCO notes. “It includes tools that allow the co-op to: control peak usage and keep power costs down, remotely manage and control the electrical distribution system, manage and resolve power outages more efficiently, integrate and manage community solar projects and improve public safety throughout the county.”

There are some drawbacks, reports Wally Gudgell from The Gudgell Group.

“It will take longer to implement, and will impact fewer businesses and households,” Gudgell writes. “While about two-thirds of the islands will eventually be covered, more remote areas will have to work with a local ISP and potentially pay more for service. DSL coverage for homes that are further than 15,000 feet from CenturyLink fiber-served distribution hubs will be challenging. Some homeowners may need to pay for fiber to be run to their homes by Islands Network (fiber direct is costly, estimated at $20/foot).”

Subscribe

Subscribe EPB this morning celebrated its fourth anniversary by thanking Chattanooga residents for supporting the utility’s fiber network with a series of price cuts and speed increases.

EPB this morning celebrated its fourth anniversary by thanking Chattanooga residents for supporting the utility’s fiber network with a series of price cuts and speed increases. Customers will see the new speeds provisioned within the next two weeks. At least 3,000 residential customers will be upgraded to gigabit service.

Customers will see the new speeds provisioned within the next two weeks. At least 3,000 residential customers will be upgraded to gigabit service.

Waiting for Comcast and Verizon to offer cutting edge broadband to 620,000 Baltimore city residents and businesses appears to be going nowhere, so the city is hiring an Internet consultant to consider whether to sell access to its existing fiber network.

Waiting for Comcast and Verizon to offer cutting edge broadband to 620,000 Baltimore city residents and businesses appears to be going nowhere, so the city is hiring an Internet consultant to consider whether to sell access to its existing fiber network. Like many cities, Baltimore already owns and operates its own fiber ring, built with public funds to support the city’s public safety radio system. Like many municipal institutional fiber networks, Baltimore’s fiber ring is underutilized. Public safety and other institutional users often use just a fraction of available capacity. Despite the fact such networks are often oversized, they are rarely controversial because they do not typically compete with commercial providers and are usually off-limits to the public.

Like many cities, Baltimore already owns and operates its own fiber ring, built with public funds to support the city’s public safety radio system. Like many municipal institutional fiber networks, Baltimore’s fiber ring is underutilized. Public safety and other institutional users often use just a fraction of available capacity. Despite the fact such networks are often oversized, they are rarely controversial because they do not typically compete with commercial providers and are usually off-limits to the public.

In brief, the judge found cable franchises are granted or denied at the municipal level by local government, not through referendums. The City of Boulder was effectively abdicating its responsibility under federal law to manage the franchising process itself. There is no provision in federal law that allows citizens to directly vote a cable franchise agreement up or down, although voters can use the ballot box to remove local officials who do not represent the will of the majority.

In brief, the judge found cable franchises are granted or denied at the municipal level by local government, not through referendums. The City of Boulder was effectively abdicating its responsibility under federal law to manage the franchising process itself. There is no provision in federal law that allows citizens to directly vote a cable franchise agreement up or down, although voters can use the ballot box to remove local officials who do not represent the will of the majority. Comcast has been a part of life in Muskegon, Mich. for decades, thanks in part to an unusually long 25-year franchise agreement signed when President Reagan was serving his last year in office. In 1988, the Berlin Wall was still in place, Mikhail Gorbachev formally implemented glasnost and perestroika, Snapple appeared on store shelves nationwide, and compact discs finally outsold vinyl records for the first time.

Comcast has been a part of life in Muskegon, Mich. for decades, thanks in part to an unusually long 25-year franchise agreement signed when President Reagan was serving his last year in office. In 1988, the Berlin Wall was still in place, Mikhail Gorbachev formally implemented glasnost and perestroika, Snapple appeared on store shelves nationwide, and compact discs finally outsold vinyl records for the first time. In December 2006, primarily at the behest of AT&T, the Michigan legislature passed a new statute that would create a uniform, statewide video franchise agreement template that providers could use to apply for or renew their franchises to operate.

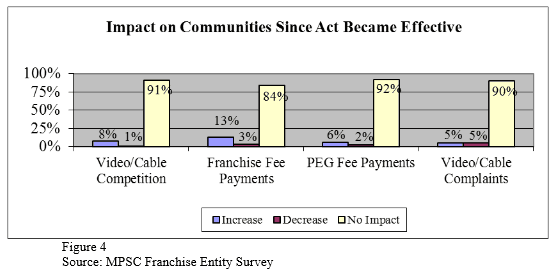

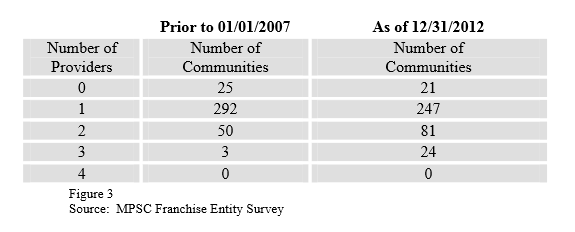

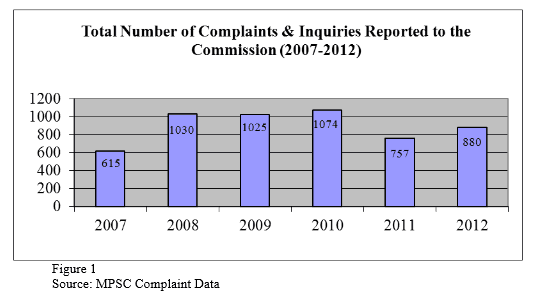

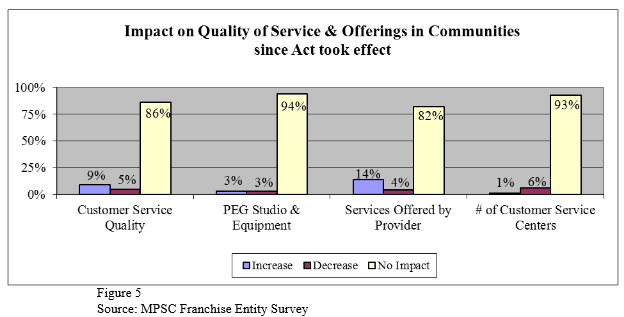

In December 2006, primarily at the behest of AT&T, the Michigan legislature passed a new statute that would create a uniform, statewide video franchise agreement template that providers could use to apply for or renew their franchises to operate.

Soon after the statewide franchise law was passed, Comcast notified the city of Detroit it could take the proposed renewal of its existing 1985 franchise agreement and go pound salt. The franchise agreement with the city expired in February 2007, just a month after the new law took effect. It was a new day, Comcast told city officials, and the company offered its own proposal for renewal — a 5% take-it-or-leave-it franchise fee and nothing else. Comcast even rejected the city’s counteroffer to include a 2% PEG fee, permitted under the new law.

Soon after the statewide franchise law was passed, Comcast notified the city of Detroit it could take the proposed renewal of its existing 1985 franchise agreement and go pound salt. The franchise agreement with the city expired in February 2007, just a month after the new law took effect. It was a new day, Comcast told city officials, and the company offered its own proposal for renewal — a 5% take-it-or-leave-it franchise fee and nothing else. Comcast even rejected the city’s counteroffer to include a 2% PEG fee, permitted under the new law.