Wheeler

The chairman of the Federal Communications Commission has foreshadowed his revised plan for Net Neutrality will include reclassification of broadband as a utility, allowing the agency to better withstand future legal challenges as it increases its oversight of the Internet.

Tom Wheeler’s latest comments came during this week’s consumer electronics show in Las Vegas. Wheeler stressed he supports reclassification of broadband, away from its current definition as an “information service” subject to Section 706 of the Telecom Act of 1996 (all two broadly written paragraphs of it) towards a traditional “telecommunications service.” Under the Communications Act of 1934, that would place broadband under Title II of the FCC’s mandate. Although at least 100 pages long, Title II has stood the test of time and has withstood corporate lawsuits and challenges for decades.

Section 706 relies almost entirely on competition to resolve disputes by allowing the marketplace to solve problems. The 1996 Telecom Act, signed into law by President Bill Clinton, sought to promote competition and end “barriers to infrastructure investment.” Broadly written with few specifics, large telecom companies have successfully argued in court that nothing in Section 706 gives the FCC the right to interfere with the marketing and development of their Internet services, including the hotly disputed issues of usage caps, speed throttling, and the fight against paid fast lanes and Internet traffic toll booths. In fact, the industry has argued increased involvement by the FCC runs contrary to the goals of Section 706 by deterring private investment.

An executive summary of a report published on the industry-funded Internet Innovation Alliance website wastes no time making that connection, stating it in the first paragraph:

Net neutrality has the potential to distort the parameters built into operator business cases in such a way as to increase the expected risk. And because it distorts the operator investment business decision, net neutrality has the potential to significantly discourage infrastructure investment. This is due to the fact that investments in infrastructure are highly sensitive to expected subscriber revenue. Anything that reduces the expectation of such revenue streams can either delay or curtail such investments.

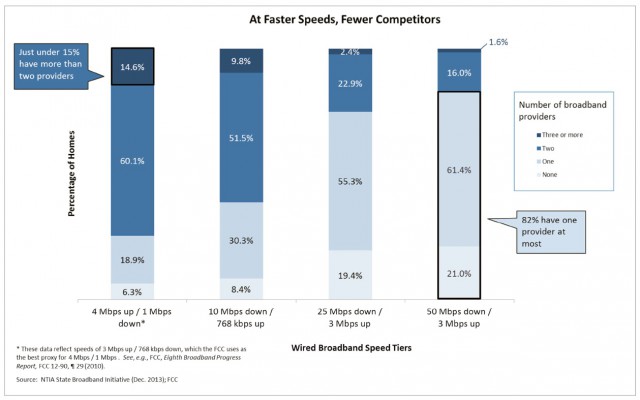

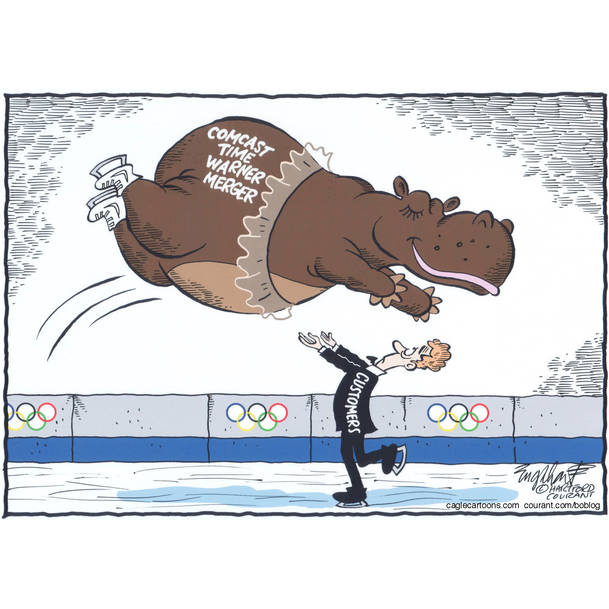

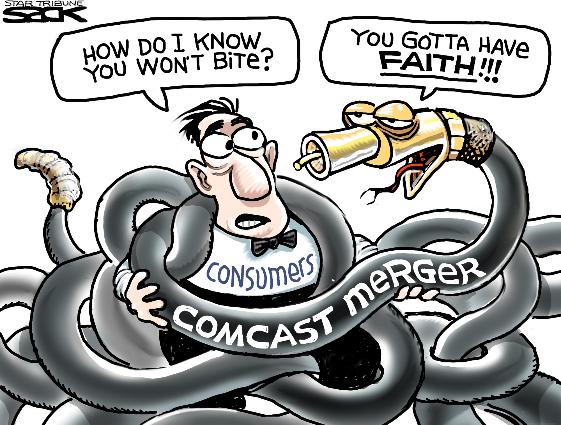

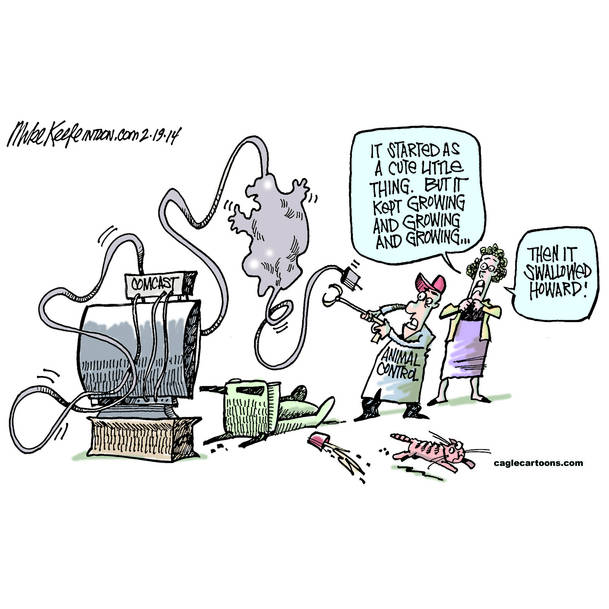

Unfortunately for consumers, even the chairman of the FCC concedes the broadband marketplace isn’t exactly teeming with the kind of competition Section 706 envisioned to keep the marketplace in check. In fact, Wheeler suggested most Americans live with a broadband duopoly, and often a monopoly when buying Internet access at speeds of 25Mbps or greater. Further industry consolidation is already underway, which further deters new competitors from entering the market.

Unfortunately for consumers, even the chairman of the FCC concedes the broadband marketplace isn’t exactly teeming with the kind of competition Section 706 envisioned to keep the marketplace in check. In fact, Wheeler suggested most Americans live with a broadband duopoly, and often a monopoly when buying Internet access at speeds of 25Mbps or greater. Further industry consolidation is already underway, which further deters new competitors from entering the market.

Net Neutrality critics, the broadband industry, and their allies on Capitol Hill have argued that adopting Title II rules for broadband will saddle ISPs with at least one hundred pages of rules originally written to manage the landline telephone monopoly of the 1930s. Title II allows the FCC to force providers to charge “just and reasonable rates” which they believe opens the door to rate regulation. It also broadly requires providers to act “in the public interest” and unambiguously prohibits companies from making “any unjust or unreasonable discrimination in charges, practices, classifications, regulations, facilities, or services.”

Both Comcast and Verizon have challenged the FCC’s authority to regulate Internet services using Section 706, and twice the courts have ruled largely in favor of the cable and phone company. Judges have no problem permitting the FCC to enforce policies that encourage competition, which has allowed the FCC some room to insist that whatever providers choose to charge customers or what they do to manage Internet traffic must be fully disclosed. The court in the Verizon case also suggested the FCC has the authority to oversee the relationship between ISPs and content providers also within a framework of promoting competition.

DC Circuit Court

But when the FCC sought to enforce specific policies governing Internet traffic using Section 706, they lost their case in court.

Although Net Neutrality critics contend the FCC has plenty of authority to enforce Net Neutrality under Section 706, in reality the FCC’s hands are tied as soon as they attempt to implement anti-blocking and anti-traffic discrimination rules.

The court found that the FCC cannot impose new rules under Section 706 that are covered by other provisions of the Communications Act.

So what does that mean, exactly?

Michael Powell, former FCC chairman, is now the chief lobbyist for the National Cable & Telecommunications Association. (Photo courtesy: NCTA)

In 2002, former FCC chairman Michael Powell (who serves today as the cable industry’s chief lobbyist) presided over the agency’s decision to classify broadband not as a telecommunications service but an “information service provider” subject to Title I oversight. Whether he realized it or not, that decision meant broadband providers would be exempt from common carrier obligations as long as they remained subject to Title I rules.

When the FCC sought to write rules requiring ISPs not block, slow or discriminate against certain Internet traffic, the court ruled they overstepped into “common carrier”-style regulations like those that originally prohibited phone companies from blocking phone calls or preventing another phone company from connecting calls to and from AT&T’s network.

If the FCC wanted to enforce rules that mimic “common carrier” regulations, the court ruled the FCC needed to demonstrate it had the regulatory authority or risk further embarrassing defeats in the courtroom. The FCC’s transparency rules requiring ISPs to disclose their rates and network management policies survived Verizon’s court challenge because the court found that policy promoted competition and did not trespass on regulations written under Title II.

The writing on the wall could not be clearer: If you want Net Neutrality to survive inevitable court challenges, you need to reclassify broadband as a telecommunications service under Title II of the Communications Act.

Major ISPs won’t hear of it however and have launched an expensive media blitz claiming that reclassification would subject them to 100 pages of regulations written for the rotary dial era. Broadband, they say, would be regulated like a 1934 landline. Some have suggested the costs of complying with the new regulations would lead to significant rate increases as well. Many Republicans in Congress want the FCC to wait until they can introduce and pass a Net Neutrality policy of their own, one that will likely heavily tilt in favor of providers. Such a bill would likely face a presidential veto.

Suggestions the FCC would voluntarily not impose outdated or irrelevant sections of Title II on the broadband industry didn’t soothe providers or their supporters. Republican FCC commissioners are also cold to the concept of reclassification.

O’Rielly

“Title II includes a host of arcane provisions,” said FCC commissioner Michael O’Rielly in a meeting in May 2014. “The idea that the commission can magically impose or sprinkle just the right amount of Title II on broadband providers is giving the commission more credit than it ever deserves.”

Providers were cautiously optimistic in 2014 they could navigate around strong Net Neutrality enforcement with the help of their lobbyists and suggestions that an industry-regulator compromise was possible. Early indications that a watered-down version of Net Neutrality was on the way came after a trial balloon was floated by Wheeler last year. Under his original concept, paid fast lanes and other network management and traffic manipulation would be allowed if it did not create undue burdens on other Internet traffic.

Net activists loudly protested Wheeler’s vision of Net Neutrality was a sellout. Wheeler’s vision was permanently laid to rest after last November when President Barack Obama suddenly announced his support for strong and unambiguous Net Neutrality protections (and reclassifying broadband as a Title II telecommunications service), No FCC chairman would likely challenge policies directly advocated by the president that nominated him.

Obama spoke, Thomas Wheeler listened. Wheeler’s revised Net Neutrality plan is likely to arrive on the desks of his fellow commissioners no later than Feb. 5, scheduled for a vote on Feb. 26. It’s a safe bet the two Republicans will oppose the proposal and the three Democrats will support it. But chairman Wheeler also listens to Congress and made it clear he doesn’t have a problem deferring to them if they feel it necessary.

“Clearly, we’re going to come out with what I hope will be the gold standard,” Wheeler told the audience in Las Vegas. “If Congress wants to come in and then say, we want to make sure that this approach doesn’t get screwed up by some crazy chairman that comes in, [those are] legitimate issues.”

If that doesn’t work, the industry plans to take care of the Net Neutrality regulation problem itself. Hours after any Net Neutrality policy successfully gets approved, AT&T has promised to challenge it in court.

[flv]http://www.phillipdampier.com/video/Fox Business News Net Neutrality Wheeler 1-8-15.flv[/flv]

Free Press CEO Craig Aaron appeared on Fox Business News to discuss Tom Wheeler’s evolving position on Net Neutrality. (3:54)

Subscribe

Subscribe

“Take a look at the chart again,” Wheeler said. “At the low end of throughput, 4Mbps and 10Mbps, the majority of Americans have a choice of only two providers. That is what economists call a “duopoly”, a marketplace that is typically characterized by less than vibrant competition. But even two “competitors” overstates the case. Counting the number of choices the consumer has on the day before their Internet service is installed does not measure their competitive alternatives the day after. Once consumers choose a broadband provider, they face high switching costs that include early termination fees, and equipment rental fees. And, if those disincentives to competition weren’t enough, the media is full of stories of consumers’ struggles to get ISPs to allow them to drop service.”

“Take a look at the chart again,” Wheeler said. “At the low end of throughput, 4Mbps and 10Mbps, the majority of Americans have a choice of only two providers. That is what economists call a “duopoly”, a marketplace that is typically characterized by less than vibrant competition. But even two “competitors” overstates the case. Counting the number of choices the consumer has on the day before their Internet service is installed does not measure their competitive alternatives the day after. Once consumers choose a broadband provider, they face high switching costs that include early termination fees, and equipment rental fees. And, if those disincentives to competition weren’t enough, the media is full of stories of consumers’ struggles to get ISPs to allow them to drop service.” Where competition exists, the Commission will protect it. Our effort opposing shrinking the number of nationwide wireless providers from four to three is an example. As applied to fixed networks, the Commission’s Order on tech transition experiments similarly starts with the belief that changes in network technology should not be a license to limit competition.

Where competition exists, the Commission will protect it. Our effort opposing shrinking the number of nationwide wireless providers from four to three is an example. As applied to fixed networks, the Commission’s Order on tech transition experiments similarly starts with the belief that changes in network technology should not be a license to limit competition. Most of the policies Wheeler seeks to influence exist on the state and local level, where he has considerably less influence. Based on the overwhelming interest shown by cities clamoring to attract Google Fiber, the problems of access to utility poles and conduit are likely overstated. The bigger issue is the lack of interest by new providers to enter entrenched monopoly/duopoly markets where they face crushing capital investment costs and catcalls from incumbent providers demanding they be forced to serve every possible customer, not selectively choose individual neighborhoods to serve. Both incumbent cable and phone companies originally entered communities free from significant competition, often guaranteed a monopoly, making the burden of wired universal service more acceptable to investors. When new entrants are anticipated to capture only 14-40 percent competitive market share at best, it is much harder to convince lenders to support infrastructure and construction expenses. That is why new providers seek primarily to serve areas where there is demonstrated demand for the service.

Most of the policies Wheeler seeks to influence exist on the state and local level, where he has considerably less influence. Based on the overwhelming interest shown by cities clamoring to attract Google Fiber, the problems of access to utility poles and conduit are likely overstated. The bigger issue is the lack of interest by new providers to enter entrenched monopoly/duopoly markets where they face crushing capital investment costs and catcalls from incumbent providers demanding they be forced to serve every possible customer, not selectively choose individual neighborhoods to serve. Both incumbent cable and phone companies originally entered communities free from significant competition, often guaranteed a monopoly, making the burden of wired universal service more acceptable to investors. When new entrants are anticipated to capture only 14-40 percent competitive market share at best, it is much harder to convince lenders to support infrastructure and construction expenses. That is why new providers seek primarily to serve areas where there is demonstrated demand for the service. More than 50 mayors of towns and cities large and small regurgitated Comcast-provided talking points in

More than 50 mayors of towns and cities large and small regurgitated Comcast-provided talking points in

In fact, since 2010 Comcast has achieved very little improvement in its abysmal score. J.D. Power & Associates reports that over the last four years, Comcast has only managed to boost its TV satisfaction score 92 points and Internet satisfaction 77 points… on a 1,000-point scale.[1]

In fact, since 2010 Comcast has achieved very little improvement in its abysmal score. J.D. Power & Associates reports that over the last four years, Comcast has only managed to boost its TV satisfaction score 92 points and Internet satisfaction 77 points… on a 1,000-point scale.[1] Among cable providers, Time Warner has the highest score of 60. Both Comcast and Charter Communications register at 56. For the private as well as public sector, including the IRS, this is the lowest level of customer satisfaction of any organization in ACSI. Consumer complaints are also much more common relative to any other measured industry. Almost half of all cable customers have registered complaints about one thing or another.

Among cable providers, Time Warner has the highest score of 60. Both Comcast and Charter Communications register at 56. For the private as well as public sector, including the IRS, this is the lowest level of customer satisfaction of any organization in ACSI. Consumer complaints are also much more common relative to any other measured industry. Almost half of all cable customers have registered complaints about one thing or another. In 2008, things deteriorated further for Comcast customers, according to this ACSI assessment:[7]

In 2008, things deteriorated further for Comcast customers, according to this ACSI assessment:[7]