Telegraph key

If you thought your Internet service was slow, consider being a customer of Cincinnati Bell’s 75 baud Telegraph Grade service, on offer to subscribers since the 1800s for low-speed stock quotes, telegrams, and office-to-home communications. But don’t consider it too long, because the service is about to be discontinued.

The first telegram in the United States was sent on Jan. 11, 1838 using the newly developed “Morse Code” system introduced by Samuel Morse. The message was sent unceremoniously across two miles of wire strung across the sprawling Speedwell Ironworks outside of Morristown, N.J. But the experiment didn’t attract much attention until it was repeated in 1844 in Washington, D.C., where members of Congress looked on as the message, “What hath God wrought” successfully traveled from Washington to Baltimore, Md. A decade later, telegraph lines were strung to every major city on the east coast. By 1861, telegraph cables stretched across the territories west of the Mississippi and reached the West Coast, putting the Pony Express out of business.

It would be a decade after that before The City and Suburban Telegraph Company, later Cincinnati Bell Telephone, was officially incorporated on July 5, 1873, becoming the first company in the city to offer direct communication between the city’s homes and businesses. Only the wealthiest families could afford a private telegraph line, which cost $300 a year provided you lived no more than a mile from the company’s office. After four years, the company only managed to attract 50 paying customers, mostly business tycoons who relied on the telegraph to stay in contact with the office while at home. Other businesses used telegraphs to connect their different offices. Most employed young men to serve as telegraph operators, translating short written messages into a series of dots and dashes and back again.

Telegraph stamps, used to prove pre-payment for telegraph messages.

Business was better further east. The story of two men that would change the course of the telegraph and launch a company that remains a household name to this day started in 1838 when banker and real estate entrepreneur Hiram Sibley moved to Rochester, N.Y. He saw plenty of opportunities in upstate New York and quickly settled in, later becoming elected Monroe County Sheriff. That position soon led to his introduction to Judge Samuel L. Selden, who had the patent rights to the House Telegraph system. Seeing an opportunity, the two embarked on their own telegraph business — the New York State Printing Telegraph Company. It did not take long for them to realize competing against the larger New York, Albany, and Buffalo Telegraph Co., was a financial disaster. The two decided it would be smarter to consolidate existing providers instead of building new networks to compete. The first craze of telecommunications company consolidation was underway. With the assistance of deep pocketed investors in Rochester, Sibley and Selden founded the New York and Mississippi Valley Printing Telegraph Company. The new entity would string some of its own telegraph lines westwards, but more importantly it would focus on acquiring its rivals, especially in areas where fierce competition kept profits low and expectations of monopoly wealth even lower.

Sibley

By 1854, Sibley and Selden were confronted with competitors using two different messaging systems among 13 different companies. Sibley’s solution? Buy them out and unify them with the Morse system, available thanks to a separate acquisition of the Erie & Michigan Telegraph Company. In 1856, the company that had its beginnings in Rochester was renamed the “Western Union Telegraph Company,” which referred to the union of the different telegraph systems of the “western states” of that era (today considered the midwest).

Between 1857 and 1861 merger mania hit almost all the telegraph companies, and by the end of this period, most formerly independent companies were owned by one of six conglomerates:

- American Telegraph Company (covering the Atlantic and some Gulf states),

- Western Union Telegraph Company (covering states North of the Ohio River and parts of Iowa, Kansas, Missouri, and Minnesota),

- New York Albany and Buffalo Electro-Magnetic Telegraph Company (covering New York State),

- Atlantic and Ohio Telegraph Company (covering Pennsylvania),

- Illinois & Mississippi Telegraph Company (covering sections of Missouri, Iowa, and Illinois),

- New Orleans & Ohio Telegraph Company (covering the southern Mississippi Valley and the Southwest).

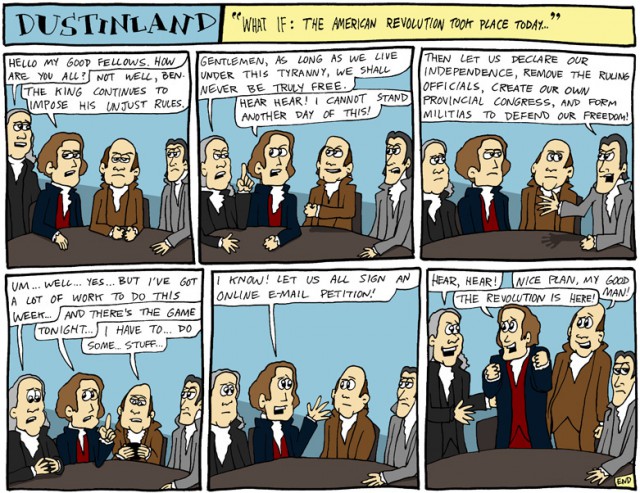

Much like the cable industry today, these six giants maintained a mutually friendly alliance and never competed for territory. Any remaining independents quickly learned cooperation with these larger systems was essential. But once competition stalled in the telegraph business, so did interest in investing in challenging upgrades.

By 1860, as the United States continued its expansion westward and tension grew between the northern and southern states over issues like slavery and self-determination, the administration of President James Buchanan realized having a reliable national telegraph network was critical to the security of the country. Unfortunately for the president, his priorities ran headlong into private company intransigence. Persuading the for-profit companies to expand their networks to connect the west coast seemed impossible. None wanted to risk investor dollars on a telegraph line they believed would be too expensive and difficult to maintain.

By 1860, as the United States continued its expansion westward and tension grew between the northern and southern states over issues like slavery and self-determination, the administration of President James Buchanan realized having a reliable national telegraph network was critical to the security of the country. Unfortunately for the president, his priorities ran headlong into private company intransigence. Persuading the for-profit companies to expand their networks to connect the west coast seemed impossible. None wanted to risk investor dollars on a telegraph line they believed would be too expensive and difficult to maintain.

That same year Congress passed, and President James Buchanan signed, the Pacific Telegraph Act, which authorized the Secretary of the Treasury to seek bids for constructing a transcontinental telegraph line, financed by the federal government. Two of the three bidders eventually dropped out, leaving Hiram Sibley’s Western Union the sole bidder.

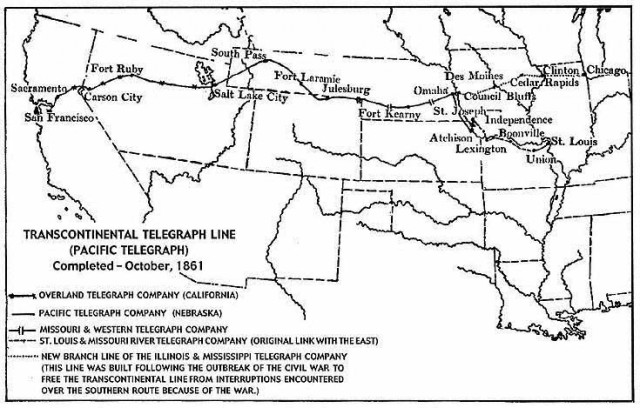

The Pacific Telegraph Act of 1860 resulted in the construction of this telegraph line extending from Nebraska to Carson City, Nev.

To insulate his other business interests from the project, Sibley organized the Pacific Telegraph Company to be responsible for construction of the new telegraph line to the west, starting in Omaha, Neb. Sibley also consolidated several small local companies into the California State Telegraph Company, which in turn launched the Overland Telegraph Company, managing construction of the cable eastward from Carson City, Nev., to Salt Lake City. The line was finally completed in October, 1861, seven months after the outbreak of the Civil War.

While newly elected president Abraham Lincoln was distracted settling into office starting March 4, 1861, Sibley was quietly preparing to consolidate control over the new taxpayer-funded cross-country cable. After the project was complete, Pacific Telegraph and California State Telegraph were quickly merged into Western Union, making Hiram Sibley the undisputed king of the telegraph industry. Any future ventures rising to challenge Western Union were instead eaten up by acquisition. By 1866, Western Union announced it was moving its company headquarters from Rochester to 145 Broadway in New York City.

Sibley retired from Western Union in 1869, and went into the seed and nursery business in Rochester and Chicago. He left the company during its most powerful era, having a virtual monopoly on the telegraph business at least a decade before the telephone would arrive on the scene. He retired the richest man in Rochester, and his home in the East Avenue Historical District still stands today. He gave generously to charity after retirement and helped incorporate a new college in the Southern Tier of New York called Cornell University.

The Hiram Sibley House, constructed in 1868, still stands today at 400 East Avenue, Rochester, N.Y.

As the 1870s arrived, the Civil War was five years finished and huge changes were coming. Although telegraph service was already in place in many eastern seaboard cities, it took longer to arrive in smaller cities in the midwest and southern United States, and it was not too long after that before the telephone followed.

In Cincinnati, the telegraph service that began in 1873 was threatened by the arrival of the telephone in 1878 — just five years later. That fall, Cincinnati’s telegraph company signed an agreement with Bell Telephone Company of Boston, the first telephone company in the country. Bell held several patents essential for manufacturing telephones and granted the telegraph company an exclusive contract to sell phone service within a 25-mile radius of the city.

Bell Telephone arrived in the era of the Robber Barons, where trusts and monopolies were the product of unfettered capitalism. Bell’s business planners were more than happy following the telegraph industry to the glory days of consolidation and monopolization.

By 1879, the Bell Telephonic Exchange was well on its way, up and running on the corner of Fourth and Walnut streets in downtown Cincinnati — the 10th phone exchange in the nation and the first in Ohio. That year, Cincinnati’s first phone book was printed and the young men that operated the telegraph lines were not welcome manning the huge expanse of manual cord boards built inside the central office.

City and Suburban believed women served as better ambassadors for the newly emerging telephone company and the concept of “Hello Girls” was born. Only later would the Bell System insist on referring to these professional employees as “operators.” In Cincinnati, around two dozen women manned the cord boards in the exchange office during its first year. They were required to memorize the names of all callers and had to quickly learn how to complete calls — a process that involved connecting a patch cable between the caller and the person called on a giant board with a plug for every subscriber. They managed nearly 150,000 completed calls during the first year for over 1,000 customers.

Jan. 1, 1935: View of half of the world’s longest switchboard at the City and Suburban Telegraph Company (later Cincinnati Bell Telephone). The board held 88 positions and handled a record of 9,722 outgoing calls in 1937. (Photo by Cincinnati Historical Society/Getty Images)

The simplicity and directness of the telephone quickly proved a major challenge for the telegraph industry. Western Union saw opportunities investing in telegraph networks overseas to stay ahead of this trend. It also launched a stock ticker service and a money transfer service, allowing people to send money across the country in a matter of hours. Despite the innovation, by 1875, financier Jay Gould had finally managed to assemble a formidable competitor to Western Union — the Atlantic and Pacific Telegraph Company. An overabundance of Western Union stock on the market by 1881 made it possible for Gould to finally launch a successful takeover.

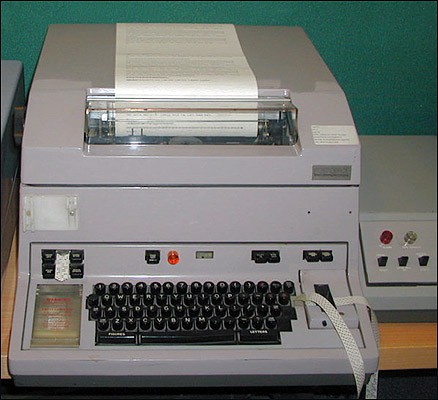

A Telex machine in use during the 1970s.

Telegraph lines remained in use well into the 20th century, used primarily for business communications, cables, and telegrams which were printed and delivered by messenger. Cincinnati Bell sold telegraph grade data lines for a variety of business applications, including slow speed data services. Even after the Morse code telegraph of the 1800s was long gone, other data services existed well before the arrival of the fax machine and the home computer. Telex messages were exchanged over a network of “teleprinters” which resembled an oversized manual typewriter. AT&T’s Teletypewriter eXchange (TWX) network was common in large businesses during the late 1960s into the 1970s. One of Cincinnati Bell’s other large customers for slow speed data lines was the military.

Cincinnati Bell customers signed up for telegraph grade service received an unconditioned telephone line capable of transmitting at 0-75 baud or 0-150 baud in half-duplex or duplex operation. That was half the data speed of computer modems common in the mid 1980s supporting up to 300 baud — which transmits text at a speed most can read and follow along in real-time.

Remarkably, Cincinnati Bell still needs the permission of regulators to drop the Civil War era telegraph service and in discontinuance requests sent to state and federal authorities, it reminded regulators the change will have no impact on the “public convenience and necessity” because there has been no demand for the service for a long time.

In fact, Cincinnati Bell has no customers to notify of the impending doom of telegraph grade service, because there have been no customers subscribed to it.

Cincinnati Bell’s request would have gone unnoticed if it wasn’t for the long legacy of the telegraph era. Western Union dispatched its last telegram on Jan. 27, 2006, after 155 years of continuous service, and largely kept quiet about it, only notifying current customers: “Effective 2006-01-27, Western Union will discontinue all Telegram and Commercial Messaging services. We regret any inconvenience this may cause you, and we thank you for your loyal patronage. If you have any questions or concerns, please contact a customer service representative.”

Cincinnati Bell’s request would have gone unnoticed if it wasn’t for the long legacy of the telegraph era. Western Union dispatched its last telegram on Jan. 27, 2006, after 155 years of continuous service, and largely kept quiet about it, only notifying current customers: “Effective 2006-01-27, Western Union will discontinue all Telegram and Commercial Messaging services. We regret any inconvenience this may cause you, and we thank you for your loyal patronage. If you have any questions or concerns, please contact a customer service representative.”

Those nostalgic for telegrams might be interested to know another company has risen where Western Union left off. iTelegram promises to bring back the experience of a messenger at your front door, but it’s a costly trip down Memory Lane. A Priority Telegram costs $28.95 + $0.75 per word and is delivered usually within 24 hours, and includes proof of delivery. A “MailGram,” dispatched through the U.S. Mail is a slightly less expensive option, costing $18.95 and includes up to 100 words. It arrives in 3-5 days. Or you could send an e-mail for approximately nothing.

While Cincinnati Bell’s request recalls a distant past, Verizon and AT&T are also asking to discontinue services that customers were still using in the 1990s. Verizon wants to drop postpaid calling cards and personal 800 services that customers used to buy from MCI, now a Verizon subsidiary. For its part, AT&T wants to drop operator-assisted services due to almost no customer demand. In many areas, dialing “0” no longer even works to reach one of those Hello Girls… pardon me, I meant operators.

Subscribe

Subscribe

If you are living with a Comcast data cap and want to see it gone, you can do something about it. Consider organizing your own local movement by tapping fellow angry customers and recruiting local activist groups to the cause. In Rochester, there was no shortage of angry college students and groups ready to protest. Google local progressive political groups, technology clubs, and technology-dependent organizations in your immediate area. Some are likely to be a good resource for building effective public protests, sign-making, and other TV-friendly protest techniques. Contact town governments, the mayor’s office of your city, technology-oriented newspaper columnists, radio talk show/computer support show hosts, etc., to build a mailing list for coordinated announcements about your efforts. Many local officials also oppose data caps.

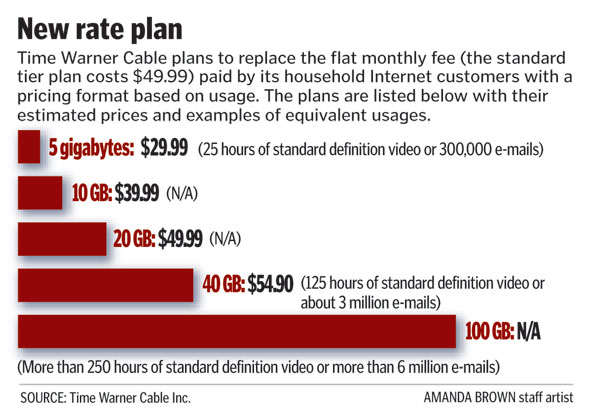

If you are living with a Comcast data cap and want to see it gone, you can do something about it. Consider organizing your own local movement by tapping fellow angry customers and recruiting local activist groups to the cause. In Rochester, there was no shortage of angry college students and groups ready to protest. Google local progressive political groups, technology clubs, and technology-dependent organizations in your immediate area. Some are likely to be a good resource for building effective public protests, sign-making, and other TV-friendly protest techniques. Contact town governments, the mayor’s office of your city, technology-oriented newspaper columnists, radio talk show/computer support show hosts, etc., to build a mailing list for coordinated announcements about your efforts. Many local officials also oppose data caps. Less than three months before announcing it would acquire Time Warner Cable in a $55 billion deal, Charter Communications quietly dropped usage caps, in place on its broadband plans since 2009, without explanation and the FCC wants to know why.

Less than three months before announcing it would acquire Time Warner Cable in a $55 billion deal, Charter Communications quietly dropped usage caps, in place on its broadband plans since 2009, without explanation and the FCC wants to know why.

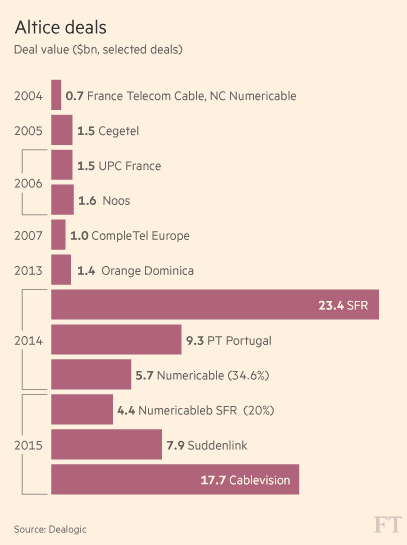

After 44 years in the cable television business, the Dolan family

After 44 years in the cable television business, the Dolan family  Malone’s reputation with the U.S. Congress reached its lowest point in the 1980s when then-Sen. Al Gore, Jr. (D-Tenn.) alternately accused Malone of heading a monopolistic cable “Cosa Nostra” that extorted his constituents with rate increases that exceeded 180% in less than five years and the “Darth Vader of Cable.” Malone taught Drahi that massive sums of money could be made buying and selling cable television (and later broadband) over systems that are usually de facto monopolies. Although entertainment is always in high demand, few governments treat the cable systems that offer it as an “essential utility,” allowing them to charge whatever they want for service.

Malone’s reputation with the U.S. Congress reached its lowest point in the 1980s when then-Sen. Al Gore, Jr. (D-Tenn.) alternately accused Malone of heading a monopolistic cable “Cosa Nostra” that extorted his constituents with rate increases that exceeded 180% in less than five years and the “Darth Vader of Cable.” Malone taught Drahi that massive sums of money could be made buying and selling cable television (and later broadband) over systems that are usually de facto monopolies. Although entertainment is always in high demand, few governments treat the cable systems that offer it as an “essential utility,” allowing them to charge whatever they want for service.

“Newspapers [in America] devote entire pages [about Drahi], emphasizing his self-made-man side which Americans love so much,” Robequain noted. She added the New York Times painted Drahi an almost romantic figure, proposing to his wife one hour after meeting her and then putting everything between them at risk to build his personal fortune.

“Newspapers [in America] devote entire pages [about Drahi], emphasizing his self-made-man side which Americans love so much,” Robequain noted. She added the New York Times painted Drahi an almost romantic figure, proposing to his wife one hour after meeting her and then putting everything between them at risk to build his personal fortune.

Cox plans to limit its gigabit customers to 2TB of usage a month. AT&T U-verse with GigaPower has a (currently unenforced) limit of 1TB a month, while Suddenlink thinks 550GB is more than enough for its gigabit customers. Comcast is market testing 300GB usage caps in several cities but strangely has no usage cap on its usage-gobbling gigabit plan. Why cap the customers least-equipped to run up usage into the ionosphere while giving gigabit customers a free pass? It doesn’t make much sense.

Cox plans to limit its gigabit customers to 2TB of usage a month. AT&T U-verse with GigaPower has a (currently unenforced) limit of 1TB a month, while Suddenlink thinks 550GB is more than enough for its gigabit customers. Comcast is market testing 300GB usage caps in several cities but strangely has no usage cap on its usage-gobbling gigabit plan. Why cap the customers least-equipped to run up usage into the ionosphere while giving gigabit customers a free pass? It doesn’t make much sense.