How exactly did America get stuck with a broadband monopoly in many areas, a duopoly in most others? It did not happen by accident. In this occasional series, “Historical Truths,” we will take you back to important moments in telecom public and regulatory policy that would later prove to be essential for the creation of today’s anti-competitive, overpriced marketplace for broadband internet service. By understanding the trickery and legislative shell games practiced by lobbyists and their elected partners in Congress, you will learn to recognize when the telecom industry and their friends are preparing to sell you another bill of goods.

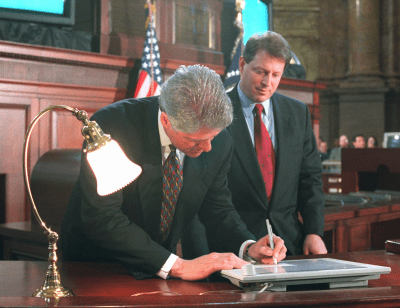

Vice President Al Gore watches President Bill Clinton digitally sign the 1996 Telecom Act into law on February 8, 1996.

By the end of the first term of the Clinton Administration, the president faced a major backlash from Republicans two years into the Gingrich Revolution. A well-funded chorus of voices in the business community, the Democratic Leadership Council — a business-friendly group of moderate Democrats, as well as commentators and pundits had the attention of the Beltway media, complaining in unison that the Democrats shifted too far to the left during the first term of the Clinton Administration, leaving it exposed in the forthcoming presidential election to another voter backlash like the one that installed the Gingrich revolutionaries in the House of Representatives and delivered a Republican takeover of the U.S. Senate in 1994.

With pressure over the growing lack of bipartisanship, and a presidential election ahead in the fall, the Clinton Administration was looking for ideas to prove it could work across the aisle and pass new laws that would deliver for ordinary Americans.

Revamping telecommunications policies would definitely touch every American with a phone line, computer, modem, and a television. Before 1996, America’s telecommunications regulation largely emanated from the Communications Act of 1934, which empowered the Federal Communications Commission to establish good order for the growing number of radio stations, telephone, and wire lines crisscrossing the country.

The 1934 Act’s legacy remains today, at least in part. It created the FCC, firmly established the concept of content regulation on the public airwaves, and established a single body to conduct federal oversight of the nation’s telephone monopoly controlled by AT&T.

Efforts to replace the 1934 Act began well before the Clinton Administration. In the early 1980s, Sen. Bob Packwood (R-Ore.) attempted to push for a legislative breakup of AT&T and a significant reduction in the oversight powers of the FCC. The bill met considerable opposition from AT&T, spending $2 million lobbying against the bill in 1981 and 1982. Alarm companies also heavily opposed the measure, terrified AT&T would enter their market and put them out of business. AT&T preferred a more orderly plan of divestiture being carefully negotiated in a settlement of a 1974 antitrust lawsuit by the Justice Department. A 1982 consent decree broke off AT&T’s control of local telephone lines by establishing seven Regional Bell Operating Companies independent of AT&T (NYNEX, Pacific Telesis, Ameritech, Bell Atlantic, Southwestern Bell Corporation, BellSouth, and US West). AT&T (technically an eighth Baby Bell) kept control of its nationwide long distance network.

Also in the 1980s, the cable television industry gained a much firmer foothold across the country, quickly gaining political power through well-financed lobbyists and close political ties to selected members of Congress (particularly Democrat Tim Wirth, who served in the House and later Senate representing the state of Colorado) that allowed them to push through a major amendment to the 1934 Act in 1984 deregulating the cable industry. The result was an early wave of industry consolidation as family owned cable companies were snapped up by a dozen or so growing operators. These buyouts were largely financed by dramatic rate increases passed on to consumers, resulting in cable bills tripling (or more) in some areas almost immediately. By the end of the 1980s, a major consumer backlash began, creating enormous energy for the eventual passage of the 1992 Cable Act, which re-regulated the industry and allowed the FCC to order immediate rate reductions.

The Progress and Freedom Foundation, with close ties to former House Speaker Newt Gingrich, closed its doors in 2010.

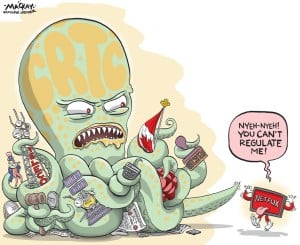

The biggest push for a near-complete revision of the 1934 Act came during the Gingrich Revolution. In 1995, the conservative Progress & Freedom Foundation — a group closely tied to then-Speaker Newt Gingrich (R-Ga.) floated a trial balloon calling for the elimination of an independent Federal Communications Commission, replaced by a stripped-down Office of Communications that would be run out of the White House and be controlled by the president. A small army of telecom industry-backed scholars also began proposing privatizing the public airwaves by selling off spectrum to companies to be owned as private property. The intense interest in the FCC by the group may have been the result of its veritable “who’s who” of telecom industry backers, including AT&T, BellSouth, Verizon, the National Cable & Telecommunications Association, cable companies like Comcast and Time Warner; cell phone companies like T-Mobile and Sprint; and broadcasters like Clear Channel Communications and Viacom.

The proposal outraged Democrats and liberal groups who called it a corporate-friendly sell-off and giveaway of the public airwaves. Then FCC Chairman Reed Hundt took the proposal very seriously, because at the time Gingrich lieutenant Tom DeLay’s (R-Tex.) secretive Project Relief group had 350 industry lobbyists, including some from BellSouth and Southwestern Bell literally drafting deregulation bills and a regulatory moratorium on behalf of the new Republican majority, coordinating campaign contributions for would-be supporters along the way. The proposal ultimately went nowhere, lost in a sea of the House Republicans’ constantly changing agendas, but did draw attention to the fact a wholesale revision of telecommunications policy would attract healthy campaign contributions from all corners of the industry — broadcasters, cable companies, phone companies, and the emerging wireless industry.

When it became known Congress was once again going to tackle telecommunications regulation, lobbyists immediately descended from their K Street perches in relentless waves, with checks in hand. There were two very important agendas in mind – deregulation, which would remove FCC rate regulation, service oversight, cross-competition prohibitions, and ownership caps, and ironically, protectionism. The cable and satellite companies had become increasingly fearful of the regional Baby Bells, which arrived in Congress in the early 1990s promoting the idea of entering the cable TV business. The cable industry feared phone companies would cross-subsidize the development of Telco TV by charging telephone ratepayers new fees to finance that entry. The cable industry had carefully developed a de facto monopoly over the prior decade of consolidation. Companies learned quickly direct head-to-head competition between two cable operators in the same market was bad for business.

The original premise of the 1996 Telecom Act was that it would eliminate regulations that discouraged competition. Promoters of the legislation asked why there should only be one phone or cable company in each city and why maintain regulations that kept cable and phone companies out of each others’ markets. Fears about market power and allowing domineering cable and phone companies to grow even larger were dismissed on the premise that a wide open marketplace, with regulations in place to protect consumers and competition would avoid creating telecom robber barons.

The original premise of the 1996 Telecom Act was that it would eliminate regulations that discouraged competition. Promoters of the legislation asked why there should only be one phone or cable company in each city and why maintain regulations that kept cable and phone companies out of each others’ markets. Fears about market power and allowing domineering cable and phone companies to grow even larger were dismissed on the premise that a wide open marketplace, with regulations in place to protect consumers and competition would avoid creating telecom robber barons.

The checks handed out by industry lobbyists were bi-partisan. Democrats could crow the new rules would finally give consumers a new choice for cable TV or phone service, and help bring the “information superhighway” of the internet to schools, libraries, and other public institutions. Republicans proclaimed it a model example of free market deregulation, promoting competition, consumer choice, and lower prices.

At a high-brow bill signing ceremony held at the Library of Congress, both President Bill Clinton and Vice President Al Gore were on hand to “electronically sign” the bill into law. Both the president and vice-president emphasized the historical significance of the emerging internet, and its ability to connect information-have’s and have-not’s in an emerging digital divide. Missing from the discussion was an exploration of what industry lobbyists and their congressional allies were doing inserting specific language into the 1996 Telecom Act that would later haunt the bill’s legacy.

On hand to celebrate the bi-partisan bill’s signing were Speaker Gingrich, Sen. Larry Pressler (R-S.D.); Sen. Ernest F. Hollings (D-S.C.); Rep. Thomas J. Bliley Jr. (R-Va.); Rep. John Dingell (D-Mich.); and Ron Brown, the Secretary of Commerce. Pressler was among the soon-to-be-endangered moderate Republicans, Hollings was a holdout against the gradual wave of Republican takeovers in southern “red states,” and Dingell was a veteran lawmaker with close ties to the broadcasting industry.

Some of the bill’s industry backers were also there, some who would ironically see its signing as directly responsible for the eventual demise of their independent companies. John Hendricks of the Discovery Channel, Glenn Jones of Jones Intercable (acquired by Comcast in 1999), Jean Monty of Northern Telecom (later Nortel), Donald Newhouse of Advance Publications (eventual part owner of Bright House Networks and later Charter Communications), William O’Shea of Reuters Ltd. and Ray Smith of Bell Atlantic (today part of Verizon) were on hand. Also in the audience was Jack Valenti of the Motion Picture Association of America, representing Hollywood Studios.

Some of the bill’s industry backers were also there, some who would ironically see its signing as directly responsible for the eventual demise of their independent companies. John Hendricks of the Discovery Channel, Glenn Jones of Jones Intercable (acquired by Comcast in 1999), Jean Monty of Northern Telecom (later Nortel), Donald Newhouse of Advance Publications (eventual part owner of Bright House Networks and later Charter Communications), William O’Shea of Reuters Ltd. and Ray Smith of Bell Atlantic (today part of Verizon) were on hand. Also in the audience was Jack Valenti of the Motion Picture Association of America, representing Hollywood Studios.

Among the fatal flaws in the Telecom Act of 1996 were its various ‘competition tests,’ which were open to considerable interpretation and latitude at the FCC. The Republican supporters of the bill argued that the presence of an open and free marketplace would, by itself, induce competition among various entrants. They were generally unconcerned with the question of whether new competition would actually arrive. Their priority was lifting the protective levers of legacy regulation as soon as possible. Many Democrats assumed what appeared to be carefully drafted regulatory language would protect consumers by preventing the FCC from lifting protections too early in the competitive process. But lobbyists consistently outmaneuvered lawmakers, finding ways to insert loopholes and compromise language that introduced inconsistencies that could be dealt with and eliminated either by the FCC or the courts later.

For example, lawmakers insisted on unbundling telecommunications network elements, an arcane way of saying new competitors must be granted access to existing networks to be shared at wholesale rates. In practice, this meant if a phone company entered the internet service provider business, it must also make its network available for other ISPs as well. In some areas, competing local telephone companies also offered landline service over existing telephone lines, paying wholesale connection fees to the incumbent local phone company. As competition emerged, the incumbent company usually petitioned for a lifting of the regulations governing their business, claiming competition had arrived.

For example, lawmakers insisted on unbundling telecommunications network elements, an arcane way of saying new competitors must be granted access to existing networks to be shared at wholesale rates. In practice, this meant if a phone company entered the internet service provider business, it must also make its network available for other ISPs as well. In some areas, competing local telephone companies also offered landline service over existing telephone lines, paying wholesale connection fees to the incumbent local phone company. As competition emerged, the incumbent company usually petitioned for a lifting of the regulations governing their business, claiming competition had arrived.

The first warning the 1996 Act was going awry came a year after the bill was signed into law. Phone companies started raising rates from $1.50-6 a month on average. AT&T was petitioning to hike rates $7 a month. Someone would have to pay to replace the scrapped subsidy system in a competitive market — subsidies that had been in place at the nation’s phone companies for decades. By charging higher rates for phone service in cities and for pricier long distance calls before the arrival of companies like MCI and Sprint, the phone companies used this revenue to subsidize their Universal Service obligations, keeping rural phone bills low and often below the real cost of providing service. To establish a truly competitive phone business, the subsidies had to be reformed or go, and that meant someone had to cover the difference.

“This game is called ‘shift and shaft,'” Sharon L. Nelson, the chairwoman of the Washington Utilities and Transportation Commission, said in 1997. “You shift the costs to the states and shaft the consumer.”

Sam Brownback (R-Kansas)

Gradually, consumers suddenly discovered their phone bill littered with a host of new charges, including the Subscriber Line Charge and various regulatory recovery fees and universal service cost recovery schemes. Phone companies also boosted rates on their unregulated Class phone features, like call waiting, caller ID, and three-way calling. The proceeds helped make up for the tens of billions in lost subsidies, but the end effect was that phone bills were still rising, despite promises of competitive, cheap phone service.

At a hearing of the Senate Commerce Committee later that year, several angry senators said they would never have voted in favor of the Telecommunications Act of 1996 if they had thought it would lead to higher rates. Sam Brownback, a Kansas Republican, was in the line of fire because of his rural constituents. Rates for those customers are subsidized more heavily than elsewhere because of the cost of extending service to them. Rates were threatening to skyrocket.

“We would be foolish to build up all these expectations about competition without saying to the American people, ‘We’re going to have to raise your phone bill,'” Brownback said.

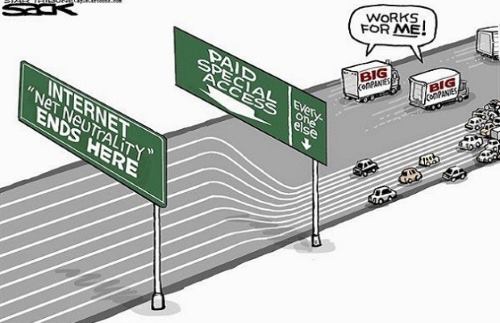

But the rate hikes were just beginning. By the beginning of the George W. Bush administration, telecom lobbyists brought a thick agenda of action items to Michael Powell’s FCC. Despite promises of competition breaking out everywhere, that simply was not the case. Republicans quickly blamed the remaining regulatory protections still in place in noncompetitive markets for ‘deterring competition.’ But the companies knew the only thing better than deregulation was deregulation without competition.

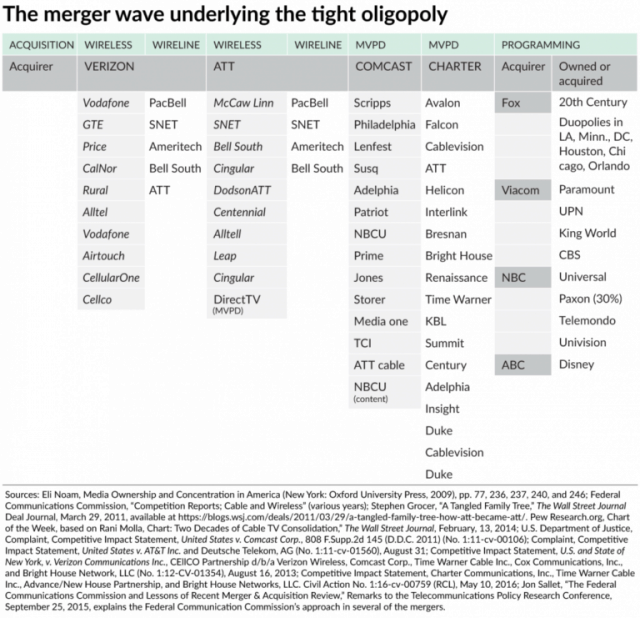

Consolidation wave

The Republican-dominated FCC quickly began removing many of those protective regulations, claiming they were outdated and unnecessary. The very definition of competition was broadened, allowing the presence of virtually any company offering almost any service good enough to trip the deregulation levers. Later, even open access to networks by competitors was often limited to pre-existing networks, not the future next generation networks. Republicans argued those networks should be managed by their owners and not subject to “unbundling” requirements.

The weakened rules also sparked one of the country’s largest consolidation waves in history. Cable companies bought other cable companies and the Baby Bells gradually started putting themselves back together into what would eventually be AT&T, Verizon, and Qwest/CenturyLink. For good measure, phone companies even snapped up a handful of independent phone companies, most notably General Telephone and Electronics, better known as GTE by Verizon and Southern New England Telephone (SNET) by AT&T.

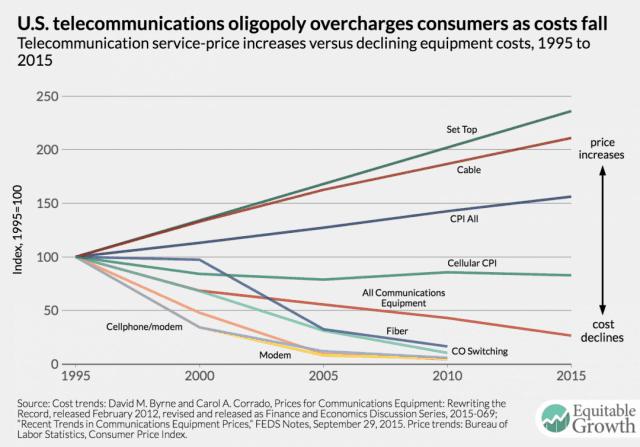

Prices rising as costs dropping.

The cable industry, under the premise it needed territories of scale to maximize potential ad insertion revenue from selling commercials on cable networks, gradually shrunk from at least a dozen well-known companies to two very large ones – Comcast and Charter, along with a few middle-sized powerhouses like Cox and Altice. Merger and acquisition deals faced little scrutiny during the Bush years of 2002-2009, usually approved with few conditions.

The result has been a rate-raising oligopoly for telecom services. In broadcasting, the consolidation wave started in radio, with entities like Clear Channel buying up hundreds of radio stations (and eventually putting the resulting giant iHeartMedia into bankruptcy) and Sinclair and similar companies acquiring masses of local television outlets. On many, local news and original programming was sacrificed, along with a significant number of employees at each station, in favor of inexpensive music, network or syndicated programming. Some stations that aired local news for 50 years ended that tradition or turned newsgathering over to a co-owned station in the same city.

Although telephone service eventually dropped in price with the advent of Voice over IP service, consumers’ cable TV and internet bills are skyrocketing at levels well in excess of inflation. Last year, the Washington Center for Equitable Growth demonstrated that the current consolidated, anti-competitive telecom marketplace results in rising prices for buyers and falling costs for providers.

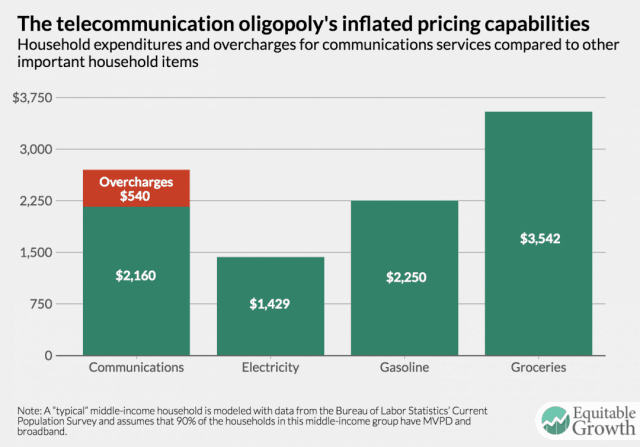

Your oligopoly tax.

“In truly competitive markets, a significant part of cost reductions would be passed through to consumers,” the group wrote. “Based on a detailed analysis of profits—primarily EBITDA—we estimate that the resulting overcharges amount to more than $45 per month, or $540 per year, an aggregate of almost $60 billion, or about 25 percent of the total average consumer’s monthly bill.”

That is one expensive bill, paid by subscribers year after year with no relief in sight. Several Republicans are proposing to double down on deregulation even more after eliminating net neutrality, which could cause your internet bill to rise further. Several Republicans want to rewrite the 1996 Telecom Act once again, and lobbyists are already sharing their ideas to further curtail consumer protections, lift ownership caps, and promote additional consolidation.

Subscribe

Subscribe

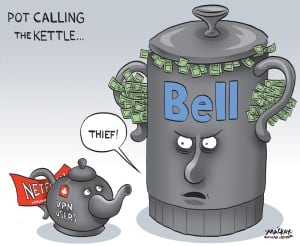

“Tou.tv (Radio-Canada’s streaming film service] is taxed. Vidéotron’s Illico is taxed; we are not talking about adding a new tax, we’re talking about taxing a product thacrticismt already exists,” Arcand said. “Are you ready to remove the taxes for those two comparable [Canadian] companies?”

“Tou.tv (Radio-Canada’s streaming film service] is taxed. Vidéotron’s Illico is taxed; we are not talking about adding a new tax, we’re talking about taxing a product thacrticismt already exists,” Arcand said. “Are you ready to remove the taxes for those two comparable [Canadian] companies?”

French language content on Netflix will largely come from European producers and networks in France and to a lesser degree Belgium and Switzerland.

French language content on Netflix will largely come from European producers and networks in France and to a lesser degree Belgium and Switzerland.

When Cisco released its 2017 predictions of internet traffic growth, once again it suggests a lot more data will need to be accommodated across America’s broadband and wireless networks. But broadband expert Dave Burstein has a good memory based on his long involvement in the industry and

When Cisco released its 2017 predictions of internet traffic growth, once again it suggests a lot more data will need to be accommodated across America’s broadband and wireless networks. But broadband expert Dave Burstein has a good memory based on his long involvement in the industry and

“U.S. wireless data traffic, which more than doubled from 2012 to 2013, increased just 26% from 2013 to 2014,” Odylzko reported. “This was a surprise to many observers, especially since there is still more than 10 times as much wireline Internet traffic than wireless Internet traffic.”

“U.S. wireless data traffic, which more than doubled from 2012 to 2013, increased just 26% from 2013 to 2014,” Odylzko reported. “This was a surprise to many observers, especially since there is still more than 10 times as much wireline Internet traffic than wireless Internet traffic.”

Both experts agree there is no evidence of any internet traffic jams and routine upgrades as a normal course of doing business remain appropriate, and do not justify some of the price and policy changes wired and wireless providers are seeking.

Both experts agree there is no evidence of any internet traffic jams and routine upgrades as a normal course of doing business remain appropriate, and do not justify some of the price and policy changes wired and wireless providers are seeking.

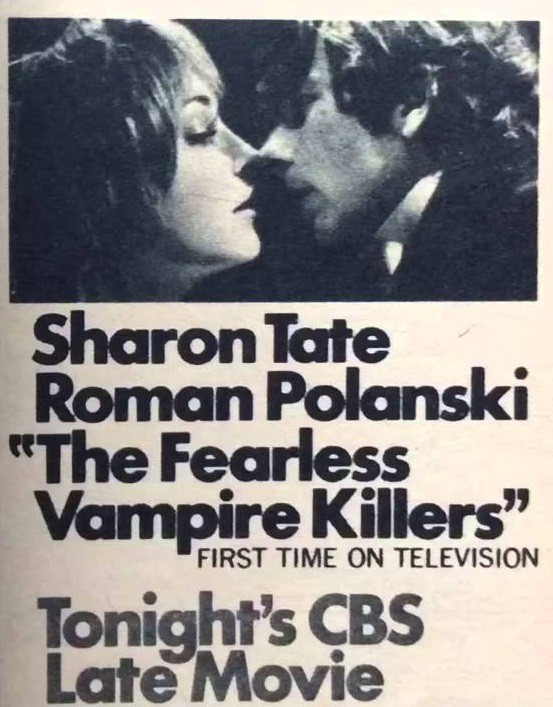

Consumers had a choice between two incompatible standards – the Sony Betamax, which promised superior video quality or JVC’s VHS format, a standard that allowed for longer recordings and was supported by just about every electronics manufacturer other than Sony. Some consumers owned both, but most settled for one or the other, and the VHS tape had a decisive advantage – extended recording time and near universal accessibility. It would eventually dominate in sales. More than 30 years later, recordings made on Betamax and VHS machines are still viewable, and turn up on video websites, often showcasing television as it used to look like in the 1970s and 1980s.

Consumers had a choice between two incompatible standards – the Sony Betamax, which promised superior video quality or JVC’s VHS format, a standard that allowed for longer recordings and was supported by just about every electronics manufacturer other than Sony. Some consumers owned both, but most settled for one or the other, and the VHS tape had a decisive advantage – extended recording time and near universal accessibility. It would eventually dominate in sales. More than 30 years later, recordings made on Betamax and VHS machines are still viewable, and turn up on video websites, often showcasing television as it used to look like in the 1970s and 1980s.

Dear Members,

Dear Members,