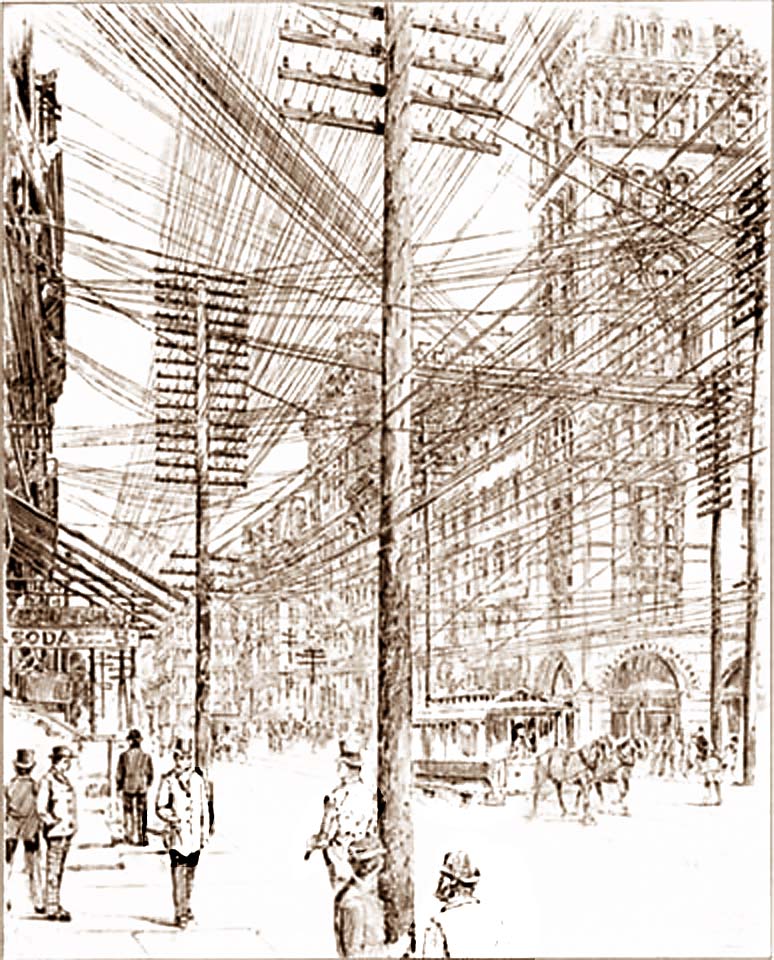

An article from McClure magazine, circa 1906, has a lot to say about today's broadband regulatory battles. We've been here before.

Yesterday, while browsing through some of the sources I review for story ideas, I encountered yet another one of those tired “free market solves everything” pieces from Randolph May, filled with the usual memes about keeping government regulation and oversight out of broadband. May, like his pro-business friends, always believes that markets are self-correcting, and that providing checks and balances for the de facto duopoly most Americans have for broadband service would ultimately harm them. Besides, if a provider gets out of hand, its competitor will pounce on the opportunity. Sometimes that happens, but often it does not. For investors, there is more money to be made going along to get along avoiding price and service wars. Indeed, when competition gets too hot and heavy, Wall Street brays that “consolidation” is required to deal with all of the revenue-losing-harm healthy competition causes. Just today, those calls are heard in the prepaid wireless market as analysts continue their relentless pounding that Leap Wireless’ Cricket must merge with MetroPCS to create cost savings, and stop price erosion (your savings).

I want to focus on May’s unintended, but disastrous comparison of American telecommunications regulation with that of the railroad industry of the 1800s:

“This form of regulation was first adopted at the federal level in the Interstate Commerce Act in 1887, which created the Interstate Commerce Commission to regulate the railroads. In 1910, the ICC was given authority to regulate newly-emerging telephone companies as common carriers, and this authority was transferred to the FCC when it was created in 1934.

By the 1980s, the railroads were largely deregulated and the ICC was abolished in 1995. And towards the end of the last century, with the emergence of competitive choices, the FCC began to relax even the regulation of POTS, or plain old telephone service, provided by formerly monopolistic telephone companies. So it was no surprise when the FCC decided to reject public utility-style regulation for the then new broadband Internet service providers.”

May is obviously no student of history, and the introduction of railroads into this argument gives me my “free market” ability to pounce on his out of hand rhetoric. The irony is that this debate takes place over the open and free Internet that May and his friends are willing to entrust to a handful of corporate providers who provide most of the connectivity in this country. They wouldn’t interfere with traffic if it meant making a pile of extra profits selling “preferred partnerships,” would they?

There are obvious metaphors between the railway industry of the 1800s and the broadband industry of 2010s. Many of the challenges are remarkably similar, especially if one considers broadband a sort of digital railroad that is becoming increasingly important to the economy and job growth.

May is lucky that nobody but those who love studying history are likely to notice he completely ignored the rationale for the Interstate Commerce Act of 1887. Railroad robber barons had by this time put such a stranglehold on the industry, entire cities prospered or withered based on what a railroad executive decided was the appropriate price for service on a schedule good enough for that community. If you lived in a city with a strong railroad system with fast lines, competition, and a healthy choice of destinations, your city generally enjoyed economic success. If you lived in an uncompetitive city deemed a railroad backwater by a provider, you paid extortionist pricing to move your goods on a limited schedule that sometimes was followed, other times not.

By the time America had caught on to these abusive practices, railroad barons were secretly charging lower prices and quietly providing rebates to their preferred partners, mostly big businesses, and overcharging everyone else. They even charged completely different rates for different products. If you transported tobacco you paid more than transporting flour. Farmers paid one price to transport crops, lumber suppliers paid something entirely different to move wood. If you were a friend of the railroad industry, and important to their lobbying efforts, you got a pass to travel fare-free.

By the time America had caught on to these abusive practices, railroad barons were secretly charging lower prices and quietly providing rebates to their preferred partners, mostly big businesses, and overcharging everyone else. They even charged completely different rates for different products. If you transported tobacco you paid more than transporting flour. Farmers paid one price to transport crops, lumber suppliers paid something entirely different to move wood. If you were a friend of the railroad industry, and important to their lobbying efforts, you got a pass to travel fare-free.

It took years for Americans to finally achieve the railroad equivalent of Net Neutrality. That’s because the railroads were politically savvy, and maintained their own version of astroturfing — an army of business leaders and supporters provided favors and money to parrot railway talking points in the media and before Congress, all while claiming they were ordinary Joe’s. Railroads supplied generous campaign contributions to members of Congress, and so much money was spread around, it eventually turned into railroad industry graft with the Crédit Mobilier scandal of 1872.

An entire class of “ordinary citizens” and business leaders pleaded in the printed press not to regulate the railway system. It would create “unintentional consequences,” would “hurt jobs,” “ruin the economy,” and would be contrary to the laissez-faire policies of the time, which allowed a completely unregulated railway system to “prosper.” Besides, railroads had “transformed the transportation infrastructure” of America and created economic benefits, all from “millions railways invested to improve railway lines.” Regulation would “discourage that investment.”

Americans might have believed that had the record of abuse by the railway industry not grown into a bulging dossier of unfair pricing and anticompetitive activities. Rural communities were charged high prices for slow, erratic railway service because they rarely had a second choice. Businesses refused to locate in communities where a monopolistic railway charged high prices and provided poor service.

But even legislative reform in 1887, designed to stop railway abuses and charge fair pricing, left enough loopholes in place for the railroad industry to continue its ways for years to follow. Court findings of wrongdoing were ignored by the industry, at least until they could successfully appeal them to federal district courts, which tended to favor business points of view in their rulings.

Sound familiar?

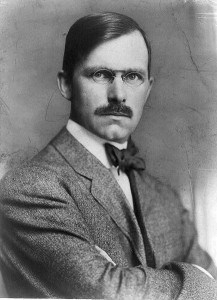

Ray Stannard Baker

But one need not take my word for it. In 1906, McClure’s magazine published the story of Danville, Virginia and its railroads by Ray Stannard Baker, a popular investigative reporter (known then as a ‘muckraker’) for the magazine. While you may be unfamiliar with Danville, located in south-central Virginia, history dealt it several interesting cards in the 1800s. Its Richmond and Danville Railroad was immortalized in the song “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down,” telling the story of how the Confederate army’s hopes of defending Richmond in the waning days of the Civil War were dashed when the Union cavalry destroyed the railroad tracks. General Lee’s army retreated to Danville — the last declared capital city of the Confederate States of America.

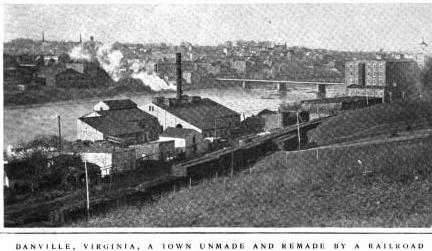

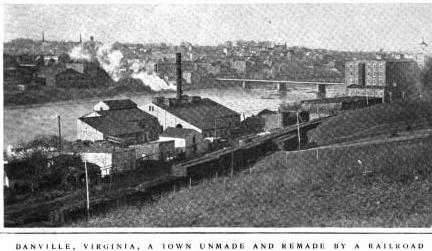

As the era of Reconstruction began, Danville threatened to become as well known as Richmond to the east and Lynchburg to the north. All three communities enjoyed the benefits of competitive railways — providing stable, affordable, and plentiful service between all three cities and points beyond. With excellent railways, an economic boom followed, and the communities prospered from manufacturing, cotton, and tobacco products, all transported on the railway system to eager buyers. What was once a city of 5,000 rapidly grew to 20,000. Danville because a world leader in tobacco production and distribution and built what was once one of the world’s largest textile mills — Dan River Industries, which survived until 2008 when the company declared bankruptcy.

Yet Danville remains completely unknown to most, a forgotten city whose early boom ended when a railway monopoly arrived and strangled the community to a former shadow of itself, perhaps never to completely recover. The effects were long-lasting. Today, Danville is a challenged city of 44,000 and declining. Lynchburg, in contrast, prospered through the manufacturing era, often called the “Pittsburgh of the South,” and has successfully transitioned into one of America’s “top 10 digital cities,” supporting its population of 73,000. Richmond towers over both, with 200,000 city residents in a community well-known nationwide. Both of those cities enjoyed competition from railways and built a substantial economic base from that that paid dividends in the decades that followed.

Of course, in 1906, the final chapter of America’s annoyance with railroad robber barons had yet to be written. Fights over pricing and service continued for years, as communities depended on railroads for their economic well-being. Ultimately, the Eisenhower Administration’s decision to undertake a national highway system, built by and supported with public funds, was symbolically the end of an era that allowed a handful of corporate executives and railroad trusts to determine the fate of entire communities, all based on the kind of railroad service they would enjoy. The highway system gave rise to the trucking industry, with air service from municipally-backed airports picking up some of the more urgent business. Railroads had to compete like they never had before.

The article, lengthy yet surprisingly accessible for contemporary audiences, is provided below in a slightly condensed form. The more you read, the more you realize those who refuse to learn from history are doomed to repeat it. Folks like Randolph May are counting on America’s ignorance of the challenges faced by our great-great grandparents, who would find familiar themes in today’s competitive and regulatory broadband battles, and who ultimately wins control of the lines and the traffic that crosses them.

The railroad industry asked people to trust them, and said notions of discriminatory pricing and access were nonsense, because they didn’t make economic sense. But they very much did, especially when alternatives were limited, if they existed at all.

At Danville, Virginia, the railroad has ceased to be a nebulous public problem, important but distant, and has become the vital concern of every citizen.

Last spring two different delegations of citizens appeared before the Interstate Commerce Committee of the Senate to explain what was the matter with the town. The first asserted with earnestness, and showed by statistics, that everything was wrong in Danville, that the railroads had ruined the town, and that stringent new laws were necessary to control them; the second with equal ardor asserted that the town was all right, that the railroad “had done a great deal for Danville,” and that legislation giving the Interstate Commerce Commission the power to change rates would be injurious, if not disastrous. These two radically opposing views were typical of the positions taken by delegations from every part of the United States: one side fighting the railroads, the other supporting them. And the impression left upon the ordinary listener was usually one of doubt and confusion as to what, after all, had been the real effect of the railroads upon the town or the industry represented.

It was with the keenest curiosity, then, that I visited Danville to discern, if I could, what really lay behind the arguments of the opposing delegations, and what, after all, had been the influence of railroads, good or bad, upon the town. If we can understand a city like Danville, which differs from other American towns only in the variety and extent of its railroad experiences, we shall go far toward understanding, broadly, the meaning of the railroad problem in this country.

Notable Signs of Decay and Growth

I feel sure that no city could give a first impression more suggestive, or convey outwardly a clearer intimation of its inward conditions. Here were evidences of both decay and growth. On many streets of the town loom with hulking relics of multiple stories built of brick, scores of them, many now vacant and out of repair; some in total ruin, burned and never rebuilt; some used part of the year for storage. Huge and grim, they present a curious picture of decay. On the other hand, almost side by side with them, bright new tobacco houses have arisen, much fewer in number but equally as large as the old — for Danville is, and has been for years, the greatest leaf tobacco market in the world.

Decay is also evident in vacant or partly vacant stores in the business part of the town, and in the lack of such prosperous jobbing houses as one ordinarily expects to find in a city of twenty thousand people. A number of wholesale merchants continue to survive but few of them are successful. On the other hand, nothing could exhale a more vaunting air of well-being than the cotton mills along the Dan River — all bright and new, prosperity beaming from every one of their thousands of windows. Within a few years Danville has come to be one of the most important cotton-milling centers in the South. Other manufacturing concerns, flour mills, a busy furniture factory, a knitgoods enterprise, also give an impression of growth and welfare.

Two Parties In Danville

A further acquaintance soon reveals the fact that the people of the town are divided into two opposing parties. The first includes a very large portion of the population — ninety-five per cent at least — and is led by the city government, the Business Men’s Association, and by prominent citizens like Judge A. M. Aiken of the corporation court, and Eugene Withers, a lawyer and former member of the legislature. This party is anti-railroad and anti-trust. It asserts that the Southern Railway has injured the growth and checked the prosperity of Danville.

The other party is small in numbers, but it represents much of the wealth of the town. It is headed by James I. Pritchett, a wealthy miller, doing a business of $900,000 a year; by R. A. Schoolfield, the president and controlling spirit of the cotton mills; by W. P. Boatwright, a prosperous furniture manufacturer; and by James R. Kopling, president of the First National Bank. This party of wealth and power stands with the railroad.

Now, it is common enough in every town to find a few rich men and many not so rich, but it is uncommon for the two interests to be so clearly conscious of their relative positions and to discuss so frankly the causes which they believe have operated in producing such remarkable contrasts of decline and prosperity. In many communities the visitor discovers an unrest which sometimes relieves itself with unreasoning attacks upon what is vaguely known as the “trust evil” or the “money power;” but in few towns will he find the people, as in Danville, calculating with exact figures, facts, even maps and diagrams, the causes which lie behind their business failures and successes. And that is what makes the conditions there so interesting.

Now, it is common enough in every town to find a few rich men and many not so rich, but it is uncommon for the two interests to be so clearly conscious of their relative positions and to discuss so frankly the causes which they believe have operated in producing such remarkable contrasts of decline and prosperity. In many communities the visitor discovers an unrest which sometimes relieves itself with unreasoning attacks upon what is vaguely known as the “trust evil” or the “money power;” but in few towns will he find the people, as in Danville, calculating with exact figures, facts, even maps and diagrams, the causes which lie behind their business failures and successes. And that is what makes the conditions there so interesting.

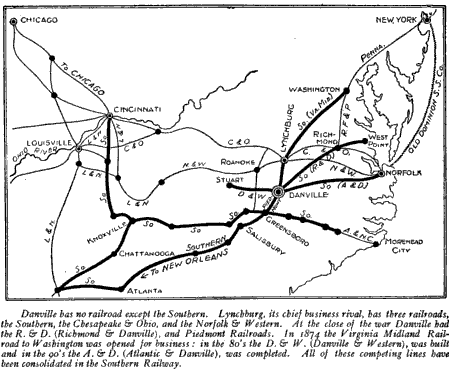

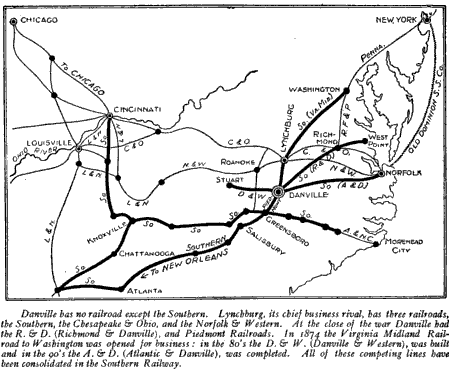

Few sections of the South recovered from the prostration of the Civil War more rapidly than southern Virginia, for the reason, chiefly, that its principal crop — tobacco — was abundant and brought ready cash. Danville, Lynchburg, and to some extent Richmond, were the energetic centers of the industry. Danville, especially, owing to its excellent location, attracted able men, and gave promise of becoming a large city. The town then had two railroads, one reaching to Richmond, where the water shipping facilities of the James River connected it with the outside world, and the other, built during the war by the Confederate government, running into North Carolina. Its nearest and only threatening rival was Lynchburg, sixty-six miles to the northwest. Both towns had good water powers, both had tobacco markets, and both did a thriving business upon practically even terms.

How Danville Helped Build Railroads

Shrewd men in Danville, as everywhere else, recognized transportation facilities as the key of industry and the chief cause of city growth. In every part of the country during the 187o’s and 188o’s the people were mortgaging their cities and counties to help private railroad builders. When the Virginia Midland Railroad was projected to run from Washington City to Danville, the citizens, eager for this new outlet into Northern markets, contributed no less than $400,000 in cash ($100,000 by the city, $300,000 by Pittsylvania County), to the projectors of the enterprise. When the railroad was completed in 1874, Danville immediately felt its vivifying effects. The town grew rapidly both in population and in wealth.

If such was the effect of railroads, said Danville, why not have more of them? The reasoning seemed good, and when the Danville & Western was projected in the 188o’s to run to the coal-fields, (where it never arrived) the city cheerfully presented the private builders with $110,000 in cash. In these years of free competition the town outstripped its rival to the north and became a thriving commercial center.

By this time the country was reaching the era of combinations, consolidations, and trusts. Short railroad lines were being connected under single ownerships. Great trunk lines took form. And one day in 1886, Danville awakened to the discovery that its two competing railroads — its only outlet to the markets of the world — had been swallowed up in the system afterwards known as the Southern Railway, which now spreads a network of lines from Washington to the Gulf of Mexico and the Mississippi River.

Danville thus found itself in 1887 at the mercy of a railroad monoply ; the competition which had been the life of its trade had wholly disappeared.

In the Grasp of Monopoly

What was the remedy? Danville did just what scores of other monopolized cities were doing at the same time. It reached out eagerly in search of new competing lines. Promoters suggested a railroad to Norfolk on the sea and Danville was so anxious to have it built that another contribution of $150,000 was raised by the town — more than enough to build outright the part of the new railroad which ran through Pittsylvania County.

The private promoters, having got all the money they could out of the people, finally completed the line — as bad a job of railroad building as they dared to do — and in the early 188o’s it was opened for business. But this new competition was not long to be enjoyed. When the Atlantic and Danville began to be a real competitor of the Southern, J. Pierpont Morgan and his associates acquired the company under a long term lease, and it became, and is now, a part of the Southern system. Since that time every railroad facility of Danville has been absolutely controlled by the Southern Railway.

When monopoly closed down upon them again, the first instinct of the people of Danville was to encourage new railroads. Their experience in the past had been bitter. They had contributed (with the county) over $700,000 in past efforts to build competing lines. The railroad companies in each case had given stock to cover the amount of money raised, and then they had failed, or reorganized — as they intended to do beforehand — and not one cent of the money voted by Danville, or by Pittsylvania County has ever been returned, or ever will be. And Danville is still paying interest on $290,000 of the money borrowed to encourage railroad competition which it does not now have. Nearly a quarter of the entire debt under which the city today struggles, is made up of these old railroad loans. “We are paying for our dead dog,” is the way one of the citizens put it to me.

When monopoly closed down upon them again, the first instinct of the people of Danville was to encourage new railroads. Their experience in the past had been bitter. They had contributed (with the county) over $700,000 in past efforts to build competing lines. The railroad companies in each case had given stock to cover the amount of money raised, and then they had failed, or reorganized — as they intended to do beforehand — and not one cent of the money voted by Danville, or by Pittsylvania County has ever been returned, or ever will be. And Danville is still paying interest on $290,000 of the money borrowed to encourage railroad competition which it does not now have. Nearly a quarter of the entire debt under which the city today struggles, is made up of these old railroad loans. “We are paying for our dead dog,” is the way one of the citizens put it to me.

These facts may seem extraordinary and unusual, but they are not. Such has been the common experience of cities and counties in every part of the United States. The people of the United States have indeed contributed enough in cash, in bonuses, and in lands (by millions of acres), to build a large proportion of the railroads of the United States. All this money and land has been given to private individuals — the owners of the railroads — and these private individuals now not only regard the railroads as their private property but deny the right of the people to a voice in the control of the vast systems thus built up.

But hope springs eternal! Danville, in spite of its former bitter experiences, was willing in 1901, by popular vote of the people, to promise $250,000 more in cash to help build another competing railroad — a project called the Mount Rogers & Eastern Railroad, which, however, from causes unknown, died before it was born.

Results of Railroad Domination

Let us examine now what railroad monopoly has done in producing the curious contrasts of decline and prosperity in Danville. Fortunately we have all the facts fully set out in hearings and court cases.

A brief study of Danville rates shows two remarkable things:

- Rates on practically all goods shipped into Danville have either remained flat or increased since the Southern Railway began its monopoly service.

- Rates on practically all goods shipped out of Danville, with one significant exception, have been greatly reduced by the same railway.

The reasons for this apparent greediness with reference to one sort of freight, and this apparent generosity regarding another sort, when explained, will make clear many of the fundamental whys and wherefores of the railroad problem.

A shoe merchant in Danville buys stock in New York. It is shipped by sea to Norfolk and by rail to Danville. He pays 66 cents per hundred pounds. In the same car maybe an exactly similar shipment for a Lynchburg merchant. The railroad company hauls the car 66 miles further, and then charges the Lynchburg man only 54 cents per hundred pounds, or 12 cents less for 66 miles more.

Why? Lynchburg has railroad competition, while Danville has not. Danville is at the sole mercy of the Southern Railway, while Lynchburg enjoys service from Southern, as well as Norfolk & Western and the Chesapeake & Ohio, any of which could have transported those shoes.

Even more remarkable examples of rate disparity exist.

Take sugar from New Orleans for example. Shipped by Southern, sugar destined for Lynchburg goes through Danville, but Danville must pay 43 cents per hundred pounds, while Lynchburg 66 miles further only pays 32 cents.

Pork shipped from Chicago to Lynchburg, a trip of 1,000 miles, costs even less! It’s just 27 cents per hundred pounds. But Danville shipments cost 40 cents. If a Danville merchant first shipped his pork order to Lynchburg, hoping to realize some savings, he’d still have to book a shipment from Lynchburg to Danville, at a price of 13 cents per hundred pounds, nearly half the price Southern charges to ship goods from Chicago some thousand miles distant, than it charges to ship between two cities only 66 miles away.

In short, railroad rates from every direction to Danville, and on almost every sort of merchandise — the only exception I could find among thousands of commodities being barreled apples — are from thirty-three per cent to one hundred per cent higher than they are to Lynchburg, and that in spite of the fact that many, if not most of the shipments for Lynchburg pass through Danville.

Curiously, Southern charges different rates for different goods, which would seem illogical for freight charged by the weight.

Story of Two Kitchen Stoves

W. R. Guerrant, a hardware merchant, showed me freight bills on two steel kitchen stoves weighing eight hundred pounds. The rate from Cincinnati to Lynchburg, five hundred miles was $1.76 while from Lynchburg to Danville, sixty-six miles, the rate was $1.84. In other words the Lynchburg merchant would have paid only $1.76 on his two stoves while the Danville merchant paid $3.60. How much chance would a Danville merchant have in competing for trade with a Lynchburg merchant?

Horses shipped from the West by the Southern can be shipped to Richmond, 141 miles further than Danville, at much less freight. There have been instances in which Danville dealers actually had their shipments billed to Richmond, and when the horses reached Danville, they took them off — secretly of course — and let the cars go on empty to Richmond.

Of course Danville has also experienced many of the lesser impositions of monopoly. Shippers have had trouble in getting cars when ordered, they have had long delays in receiving freight, and they have also suffered exasperating passenger train arrangements and poor service in other ways. With no danger of any competitor getting the business the railroad could do as it liked.

As a result of high and discriminating freight rates the wholesale business of Danville, once thriving and prosperous, has been injured and the retail business has also suffered. Jobbers in other Virginia cities have taken away practically all of Danville’s trade, even selling to merchants in smaller villages almost in the environs of Danville. Every commodity in Danville is higher in cost than in other cities, therefore no farmer or any one else trades in Danville if he can avoid it. And every citizen pays the tax of monopoly upon every pound of sugar, loaf of bread, ton of coal, every hat, every foot of lumber, all shipped by Southern Railway.

After a careful investigation the Interstate Commerce Commission said in its report:

Danville began twenty years ago with a population of 3,ooo people, and rapidly developed to substantially its present size; but in recent years and at the present time it finds further development seriously impaired, if not absolutely checked by this rate discrimination. Its wholesale merchants are deprived of most of their profitable territory by competition with Lynchburg and Richmond. Every new industry which considers the advisability of locating there is confronted with the fact that it must pay in freight rates a sum from Danville over and above what must be paid from Lynchburg large enough to afford a handsome profit upon many enterprises. Every inhabitant and every property owner of Danville is to an extent injured by this discrimination.

All this accounts for the vacant or partially vacant stores, it also accounts for the rise of the anti-railroad party among the people, and the fact that the city government, the Business Men’s Association, and many prominent citizens are waging a hard fight for new laws to control railroad rates.

Where the Railroads Smiled

While the railroads extract a high price for goods shipped into Danville, the reverse is true for many goods heading out of town.

In Danville, most freight consists of cotton goods, furniture, flour, and tobacco.

A railroad seeks to build up industries on its own line. It also favors the big shipper who can assure so many carloads every year.

Cotton mills, for example, would not be built at Danville unless the railroad first gave favorable rates. And we find that Mr. Schoolfield has built up huge mills because he can ship his cotton at rates which permit him to compete with other cotton mills in the South.

Mr. Pritchett is given a milling-in-transit rate on wheat — in other words, he is allowed to stop wheat in Danville, grind it in his mill, and send the flour on at the remainder of the rate. If he had not that rate he couldn’t thrive – but he is highly prosperous.

Both of these gentlemen chiefly use water from the Dan River for their power, not the coal which bears such high freight rates. The railroad does not have a monopoly on water.

Mr. Boatwright gets good rates on his furniture, so he is prosperous. Here is a curious fact: furniture can be shipped from Mr, Boatwright’s factory at Danville, to Northern cities, much cheaper than it can be shipped from the North to the retail merchants at Danville. In other words, by the favor of the railroad, Mr. Boatwright is enabled to get his furniture out of Danville at a low rate so that he can compete with other manufacturers; but furniture shipped in and bought by the people of Danville (who can’t escape) must pay the high rates.

The one exception to this rule in tobacco, which costs the same high price to ship into town as it costs to export it. That’s because the local farmers that grow it often live on subsistence wages, ill-equipped to follow Mssrs. Boatright, Pritchett, and Schoolfield out of town in a snit over railway rates.

Many a dollar can be made off the plight of farmers, who often must borrow money to advance to the railways, hopefully recouped upon sale of their goods in distant cities. Bankers provide the loans, and support for the current railway arrangements that provide them a profitable side business.

It is plain, now, why the rich men of Danville — the manufacturers and to some extent the bankers — stand with the railroads. It is purely selfish: They get favoring rates and they stand by the monopoly. If they did not, a very little change in a rate might destroy their business. And the friendlier they are, the more favors they are likely to get.

Mr. Pritchett said to the Senate Committee :

“In my past experience of twenty odd years in business I have found the officials of Southern Railway always willing to listen to our troubles and in a great many instances to take care of us.”

Mr. Pritchett not only gets favorable rates, but he is a director of one branch of the Southern Railway.

Thus the two contrasting groups went to Washington last spring. The committee of citizens went at its own expense, to complain of the oppression of the monopoly. The committee of rich manufacturers and bankers was called together by a director of one of the branches of the Southern Railway, and the members traveled on free passes.

The Costs Go Beyond the Railroads

The Costs Go Beyond the Railroads

The citizens of Danville show by accurate figures that while Lynchburg has grown rapidly the population of Danville (not counting suburbs admitted), has increased comparatively little since the railroad monopoly fastened upon the town. Another barometer of prosperity is the valuation of real estate: up to 1887 — the year of monopoly — the increase in value was rapid. In 1885 it was $5,511,097. In 1890 it had decreased to $5,170,928. In 1900 it had increased to $6,828,760, but this was caused largely by the addition of over $1,000,000 of cotton-mill property which had been exempt for ten years from any taxation whatever. In 1904 the taxable values had decreased again to $6,521,005.

At the same time that values decreased the tax rate has gone up steadily — for the city must still, in addition to many other expenses, pay interest on its contributions toward the building of the various branches of what is now the Southern Railway.

“We hear the argument of the railroads,” says Eugene Withers, one of the spokesmen of the citizens’ committee, “that governmental rate regulation will confiscate railroad property, but we don’t hear anything at all about how the railroads now confiscate the people’s property.”

Who Are Really Prosperous in Danville?

It will thus be seen that every moneyed interest concerned in the Danville situation — the railroad owners, the tobacco trust, and the favored manufacturers — have been highly prosperous, while the producer and the consumer — in other words the people who do the actual work — have had to bear heavy burdens of excessive freight rates and of prices manipulated by the trusts, to say nothing of constantly increasing taxation.

The manufacturers at Danville assert that the enterprises of Danville are larger than ever before, that more money is invested there, that the profits are greater, that more freight-is being shipped every year, and that the banks do a more extensive business. This is probably true to the last word. The same view was presented by the manufacturers at Washington last spring, and to one unfamiliar with actual conditions it looks like a rosy picture. But that isn’t true with the common man in Danville.

I was greatly struck with the words of Judge Aiken upon this very point. Perhaps no man in Pittsylvania county has a wider acquaintance with conditions and men.

” The long continuance of this condition has affected our citizenship,” he said. “I have been on the bench for twenty years, and I can perceive it in the selection of juries.”

We may now begin to see why the great proportion of people in Danville, led by the city government, are anti-railroad and antitrust, and why they sent a committee to Washington to protest and demand laws to control railroad monopoly. On the other hand we can see why the few rich men, who are growing richer every year, went to Washington and supported the railroad monopoly, and declared that Danville was more prosperous than ever before. And it is more prosperous — for six, or twenty, or perhaps even one hundred men, but for the remainder of the population it is far less prosperous.

When the news came to Danville that six manufacturers and bankers had gone to Washington to support the railroads, the people were so much stirred that they called a great mass-meeting at the court-house — one of the most remarkable gatherings in the history of the town. So bitter was the feeling aroused, that it was only the council of cooler heads that prevented severe denunciations of abuse. Here was the town trying to escape from the burden of railroad monopoly; and here were six citizens of the town, who, because they received favoring rates, and were personally prosperous, were willing to prevent their neighbors from obtaining any relief. One of the speakers at the meeting, Mr. Withers, thus expressed it:

“It is not a question between the two committees. If certain businesses are satisfied with the rates given them by the Southern Railway, why should they interfere with those who are not satisfied with the rates?”

One of the first things a visitor at Danville is prompted to ask is, “Why don’t you complain to the Interstate Commerce Commission? Why don’t you carry your grievances into the courts?”

One of the first things a visitor at Danville is prompted to ask is, “Why don’t you complain to the Interstate Commerce Commission? Why don’t you carry your grievances into the courts?”

That is exactly what Danville has done: few other American cities have conducted a longer or a more persistent fight. No part of the Danville story, indeed, is more important or significant than this. Twice the city achieved legal victory before the Commission, and twice the railroads ignored the ruling.

Indeed, through changes in classification about that time, rates were actually increased on many commodities. The Southern Railway paid no attention whatever to the Interstate Commerce Commission, and Danville continued to pay the high freight rates. The next year, 1901, the Commission went into the courts to enforce its order. A railroad is perfectly at home in the courts; it has trained, high-grade legal talent and plenty of money, and the more delay the better, because in a few months time a town like Danville would pay in extortionate rates more than enough to cover any amount of litigation. The case dragged, therefore, until August, 1902, when the federal court decided in favor of the Southern Railway and overturned the decision of the Commission. The case was then carried to the Circuit Court of Appeals where nearly a year more of time was consumed, and the railroad again won the case. At this point the Interstate Commerce Commission stopped fighting and the rates are unchanged today at Danville.

What Is the Railroad Position?

Now, I do not wish to infer that the Southern Railway has adjusted the Danville rates out of spite. The Southern Railway is on its part and in its way a victim of competitory conditions, and it was the setting forth of these conditions which won the case in the federal courts. Rates at Lynchburg are forced down by competition and are therefore beyond the control of the Southern Railway, acting alone. In order to make up for low rates at towns where competition exists the Southern Railway exacts high rates at towns where it has a monopoly. In other words, Danville must be made to help pay Lynchburg’s freight. Considering only the dividends of the railroad this sort of an adjustment may be necessary, and the courts may sustain it; but does that make it right or just either to Lynchburg or to Danville? Are towns created for the profit of highway owners, or are highways built to serve the towns? The railroad asserts that it is powerless to adjust present conditions so as to do justice between such towns as Danville and Lynchburg, but when it is proposed to create a government tribunal with power to secure that justice, the railroad fights the proposition, as it is fighting it now in Congress.

What Of Our Elected Leaders?

The time is coming when the people will insist upon knowing, not only the personal qualities of its governors and congressmen, and especially its United States Senators, but it will also find out definitely and exactly who these men propose to represent — the railroads and the trusts, or the people. If Senator Martin, of Virginia, for example, is not right upon the railroad questions from the point of view of Danville, isn’t it largely the fault of Danville? Until the people in each state follow up their senators and find out what they stand for, and then hold them to their positions, they will get little progressive legislation in Congress. When Minnesota elected Senator Clapp — who had for years been a railroad attorney — they not only asked him what he stood for, but got his promise in writing that he would support a rate regulation law.

Of course the railroad has great influence within Danville, as in other towns. Several of the branch lines of the Southern Railway still maintain a corporate existence. They must have Virginia directors — merely nominal officers, of course, without power. Eight or ten of these directorships are scattered among the citizens of Danville, presumably where they will do the most good. Each director gets an annual free railroad pass. Here, at the start, is a nucleus of a railroad party in Danville. The head of the cotton mill company is one of these directors, the head of the flour mill company is another; both were members of the committee which went to Washington to tell the Senate that railroad conditions in Danville were all right, and that no more legislation was needed.

Conclusions From the Danville Case

I have thus endeavored to give a clear idea of what conditions are in Danville. A few points in conclusion, should be emphasized.

Is it right that the Southern Railway, having a monopoly, should charge high rates at Danville to make up for the low competitive rates at Lynchburg? Should Danville help to pay Lynchburg’s freight rates? The Southern Railway admits making a profit on its Lynchburg business, even at the low competitive rates: why, then, should Danville be required to pay from thirty to one hundred percent more profit?

Is it right that the very life of a town in Virginia should be in the hands of private individuals in New York city or elsewhere, who have no sympathy with Danville, and are working, not for justice, but for private profit?

Railroads are public highways which all people have a right to use upon equal terms. Is it right for the Southern Railway, upon any excuse whatever, to deny the people of Danville this equality upon the public highway?

Is it right that the Southern Railway, having deprived Danville of competition, should now plead its own wrong in defense of high rates at Danville and low rates at Lynchburg? If the beggar on the streets has no right to steal money because he is a beggar, has the Southern Railway a right to do a wrong merely because it needs revenue?

Is it right that a railroad which objects so strongly to the confiscation of its property, should be allowed to depreciate the value of property in towns where it has a monopoly?

The railroad says that such adjustments as those between Lynchburg and Danville are fixed by competitory conditions beyond its control. If the railroad cannot itself cure such injustice, why should not the governmental commission be empowered to do it?

Is it right, finally, that there should be no power in this country strong enough to prevent railroad injustice and railroad discriminations like those existing in Danville?

If you would like to read the article in its entirety, as well as read other articles from McClure’s in 1906, you can download this PDF copy (32 MB) of the magazine, which includes several issues. The article regarding the railroad industry begins on page 131.

Subscribe

Subscribe