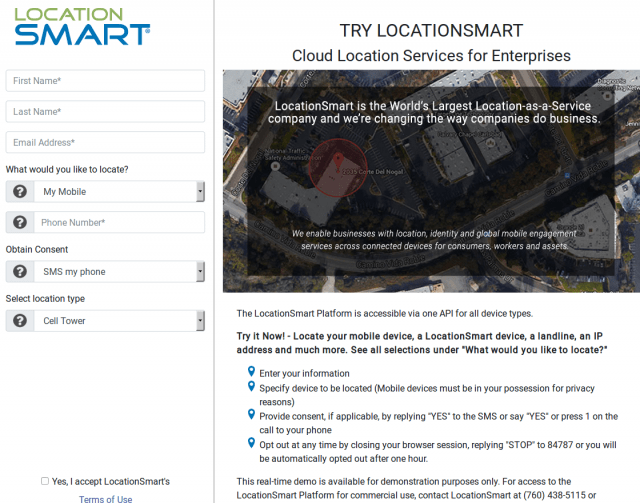

Go ahead, enjoy a free trial and locate (within 100 yards) your ex-boyfriend or girlfriend, husband, wife, or friends. This online demo had few security checks to keep unauthorized users out, despite claims consent was required. (Image courtesy of: Krebs on Security)

A company best known for providing phone service to prisoners and monitoring inmate locations has sold access to the whereabouts of almost every powered-on cellphone in the country without verifying a court order, thanks to a lucrative partnership with America’s top four cell phone companies.

The service, provided by Securus, has proved a handy tool for law enforcement agencies nationwide, allowing one former sheriff of Mississippi County, Mo., to track the whereabouts of a judge and members of the State Highway Patrol, all without their consent.

The service, provided by Securus, has proved a handy tool for law enforcement agencies nationwide, allowing one former sheriff of Mississippi County, Mo., to track the whereabouts of a judge and members of the State Highway Patrol, all without their consent.

The New York Times reported in May that despite repeated assurances from cell phone companies that location data sold to third parties would not include personally identifiable information, it now appears in fact, it often does, and not just information about a particular company’s own customers.

Securus’ location service has been available since at least 2013, although some claim the service has been active for much longer than that, and after recent attention from Congress, Verizon, AT&T, and Sprint have announced they will suspend the sale of location data to most third parties as soon as contract termination notices can be sent.

The industry’s commitments to customer privacy appear to be tissue thin, based on the confidential contracts companies like Verizon and AT&T sign with third-party data aggregators, who in turn resell each provider’s location service to an even broader range of companies. Sen. Ron Wyden (D-Ore.) called the contracts “the legal equivalent of a pinky promise” in a letter sent to the Federal Communications Commission.

Verizon, T-Mobile, AT&T, and Sprint all have contracts with two of the country’s largest resellers of location data – LocationSmart and Zumigo. The contracts allow the two firms to pull cellphone users’ locations in real time and sell that information to other companies, including Securus. The contracts claim to need users’ consent before their location information can be revealed, which is either done in an app directly requesting location data or in a thicket of fine print terms and conditions most consumers never read. There is scant evidence cell phone companies independently audit consent records, which means a company or app author could claim blanket consent.

Verizon, T-Mobile, AT&T, and Sprint all have contracts with two of the country’s largest resellers of location data – LocationSmart and Zumigo. The contracts allow the two firms to pull cellphone users’ locations in real time and sell that information to other companies, including Securus. The contracts claim to need users’ consent before their location information can be revealed, which is either done in an app directly requesting location data or in a thicket of fine print terms and conditions most consumers never read. There is scant evidence cell phone companies independently audit consent records, which means a company or app author could claim blanket consent.

Securus never had a contact with many of the people it tracked — often those suspected of a crime or law enforcement officers. Securus operates its service under provisions permitting law enforcement to access location data without the consent of those being tracked, as long as the law enforcement agency attests to the legality of its request. Laws requiring court orders to track cellphone users vary considerably in different states. Some require a judge’s signature on a court order, others demand a notarized statement from a law enforcement official, while others require no independent review at all.

Cell phone companies may have a loophole to escape legal culpability for revealing private personal location information to unauthorized third parties. Privacy laws have never offered strong privacy protections to consumers for telecommunications services. In March 2017, the Republican majority in Congress stripped what privacy protections did exist during the Obama Administration in a mostly party-line vote condemned by Democrats. After the rules were repealed, mobile providers can track and share people’s browsing and app activity without permission. Several Democrats warned the move would lead to an eventual scandal when providers were caught collecting and selling sensitive personal information without customer consent.

As long as they are following their own voluntary privacy policies, carriers “are largely free to do what they want with the information they obtain, including location information, as long as it’s unrelated to a phone call,” Albert Gidari, the consulting director of privacy at the Stanford Center for Internet and Society and a former technology and telecommunications lawyer told the New York Times. If a cellphone is powered on, constantly updated location information accurate within a few hundred feet is available for sale.

Because cell phone companies work with third-party aggregators, they can claim any privacy violations could be the result of unauthorized or inappropriate use of their location tools. But finding which company ultimately violated a consumers’ privacy requires investigative work because services like LocationSmart also sell services to other aggregators, who in turn sell services to a myriad of companies. That is what appears to have happened with Securus, who accessed location services through a mobile marketing company called 3Cinteractive, which in turn has a contract with LocationSmart. That means a provider can claim at least three layers of possible third-party liability, because requests moved through several hands:

Because cell phone companies work with third-party aggregators, they can claim any privacy violations could be the result of unauthorized or inappropriate use of their location tools. But finding which company ultimately violated a consumers’ privacy requires investigative work because services like LocationSmart also sell services to other aggregators, who in turn sell services to a myriad of companies. That is what appears to have happened with Securus, who accessed location services through a mobile marketing company called 3Cinteractive, which in turn has a contract with LocationSmart. That means a provider can claim at least three layers of possible third-party liability, because requests moved through several hands:

Example: Law enforcement agency request -> Securus -> 3Cinteractive -> LocationSmart -> Verizon

Although law enforcement agencies are supposed to upload legal documents proving informed consent laws do not apply to a particular request, it appears the validity of those documents was not independently verified.

“Securus is neither a judge nor a district attorney, and the responsibility of ensuring the legal adequacy of supporting documentation lies with our law enforcement customers and their counsel,” a Securus spokesman said in a statement. Securus offers services only to law enforcement and corrections facilities, and not all officials at a given location have access to the system, the spokesman added.

But those that did could abuse the system with few consequences. In fact, a security hole left open for a year by LocationSmart appears to have let almost anyone use the service to find friends, family, or anyone else, thanks to a helpful free demo for prospective clients revealed by Robert Xiao, a security researcher at Carnegie Mellon University:

LocationSmart’s demo is a free service (Editor’s Note: the demo has since been locked down) that allows anyone to see the approximate location of their own mobile phone, just by entering their name, email address and phone number into a form on the site. LocationSmart then texts the phone number supplied by the user and requests permission to ping that device’s nearest cellular network tower.

Once that consent is obtained, LocationSmart texts the subscriber their approximate longitude and latitude, plotting the coordinates on a Google Street View map. [It also potentially collects and stores a great deal of technical data about your mobile device. For example, according to their privacy policy that information “may include, but is not limited to, device latitude/longitude, accuracy, heading, speed, and altitude, cell tower, Wi-Fi access point, or IP address information”].

But according to Xiao, a PhD candidate at CMU’s Human-Computer Interaction Institute, this same service failed to perform basic checks to prevent anonymous and unauthorized queries. Translation: Anyone with a modicum of knowledge about how Web sites work could abuse the LocationSmart demo site to figure out how to conduct mobile number location lookups at will, all without ever having to supply a password or other credentials.

“I stumbled upon this almost by accident, and it wasn’t terribly hard to do,” Xiao said. “This is something anyone could discover with minimal effort. And the gist of it is I can track most peoples’ cell phone without their consent.”

Obtaining customer consent to share location details appears to not always be a priority of the location data resellers. For them, a lucrative business depends on easy access to location information that can be sold for targeted marketing campaigns (such as texting a coupon offer when entering a store or sending a special offer if you appear to be visiting a competitor’s store), tracking packages, service calls, or deliveries (such as tracking the cable repair technician, the location of your pizza, or where the parcel service driver is with a package you ordered), or allowing your bank to flag a suspicious credit card transaction when they discover your cellphone is nowhere near the store where the purchase just occurred.

Wyden

The personal risks of unauthorized access are too numerous to count, starting with former boyfriends or girlfriends cyberstalking one’s live location, criminals tracking a target, and law enforcement officials violating your rights.

The revelations in the New York Times, published on May 10, have attracted the sudden attention from America’s largest cell phone companies this week because of Sen. Wyden’s letter informing them they are under scrutiny. No cell phone company wants to endure the media spotlight Facebook has been under since revelations it exposed the personal data of as many as 87 million users without their consent. The carriers, except for T-Mobile, have announced a lock-down.

Verizon: Verizon Communications pledged to stop selling individual customer locations to data brokers, and will wind down contracts with LocationSmart and Zumigo, a competing data aggregator. “We will not enter into new location aggregation arrangements unless and until we are comfortable that we can adequately protect our customers’ location data,” Verizon privacy chief Karen Zacharia wrote in a June 15 letter to Wyden. Verizon did not explain why it took at least two years for the lock-down to begin.

AT&T: Said it “will be ending our work with aggregators for these services as soon as practical in a way that preserves important, potential lifesaving services like emergency roadside assistance.”

Sprint: “Suspended all services with LocationSmart” last month and “is beginning the process of terminating its current contracts with data aggregators to whom we provide location data.” A spokeswoman said that effort “will take some time in order to unwind services to consumers, such as roadside assistance and fraud prevention services.”

T-Mobile: Stopped short of terminating agreements, T-Mobile executives told Wyden it “started one of our periodic reviews several months ago and selected a third-party to assess this program.”

Securus: Securus spokesman Mark Southland said in a statement that the company adheres to its contract, adding that cutting off law enforcement access to location tools “will hurt public safety and put Americans at risk.”

Read the full letters from America’s top-four mobile companies:

Subscribe

Subscribe

21st Century Fox has accepted an improved $71.3 billion bid from Walt Disney Co. to acquire its entertainment division, outbidding Comcast’s all-cash $65 billion bid for Fox’s content companies.

21st Century Fox has accepted an improved $71.3 billion bid from Walt Disney Co. to acquire its entertainment division, outbidding Comcast’s all-cash $65 billion bid for Fox’s content companies.

The service, provided by Securus, has proved a handy tool for law enforcement agencies nationwide, allowing one former sheriff of Mississippi County, Mo., to track the whereabouts of a judge and members of the State Highway Patrol, all without their consent.

The service, provided by Securus, has proved a handy tool for law enforcement agencies nationwide, allowing one former sheriff of Mississippi County, Mo., to track the whereabouts of a judge and members of the State Highway Patrol, all without their consent. Verizon, T-Mobile, AT&T, and Sprint all have contracts with two of the country’s largest resellers of location data – LocationSmart and Zumigo. The contracts allow the two firms to pull cellphone users’ locations in real time and sell that information to other companies, including Securus. The contracts claim to need users’ consent before their location information can be revealed, which is either done in an app directly requesting location data or in a thicket of fine print terms and conditions most consumers never read. There is scant evidence cell phone companies independently audit consent records, which means a company or app author could claim blanket consent.

Verizon, T-Mobile, AT&T, and Sprint all have contracts with two of the country’s largest resellers of location data – LocationSmart and Zumigo. The contracts allow the two firms to pull cellphone users’ locations in real time and sell that information to other companies, including Securus. The contracts claim to need users’ consent before their location information can be revealed, which is either done in an app directly requesting location data or in a thicket of fine print terms and conditions most consumers never read. There is scant evidence cell phone companies independently audit consent records, which means a company or app author could claim blanket consent. Because cell phone companies work with third-party aggregators, they can claim any privacy violations could be the result of unauthorized or inappropriate use of their location tools. But finding which company ultimately violated a consumers’ privacy requires investigative work because services like LocationSmart also sell services to other aggregators, who in turn sell services to a myriad of companies. That is what appears to have happened with Securus, who accessed location services through a mobile marketing company called 3Cinteractive, which in turn has a contract with LocationSmart. That means a provider can claim at least three layers of possible third-party liability, because requests moved through several hands:

Because cell phone companies work with third-party aggregators, they can claim any privacy violations could be the result of unauthorized or inappropriate use of their location tools. But finding which company ultimately violated a consumers’ privacy requires investigative work because services like LocationSmart also sell services to other aggregators, who in turn sell services to a myriad of companies. That is what appears to have happened with Securus, who accessed location services through a mobile marketing company called 3Cinteractive, which in turn has a contract with LocationSmart. That means a provider can claim at least three layers of possible third-party liability, because requests moved through several hands:

The article in Light Reading

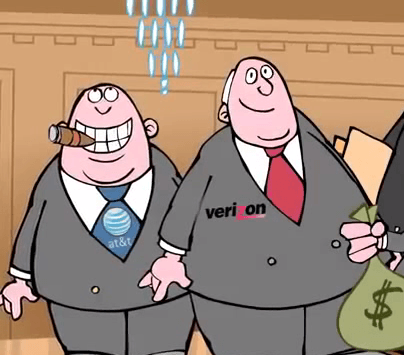

The article in Light Reading  The more debt (and debt payments) that pile up at the two companies, the less money will be available to spend on fiber upgrades. In fact, there is evidence these companies are hoping to further cut costs in their core landline network operations. Some regulators have noticed. Verizon was forced to make a deal with New York regulators requiring the company to spend millions replacing failing copper-based facilities and upgrade them to fiber and remove or replace tens of thousands of deteriorated utility poles. Verizon faced similar action in Pennsylvania.

The more debt (and debt payments) that pile up at the two companies, the less money will be available to spend on fiber upgrades. In fact, there is evidence these companies are hoping to further cut costs in their core landline network operations. Some regulators have noticed. Verizon was forced to make a deal with New York regulators requiring the company to spend millions replacing failing copper-based facilities and upgrade them to fiber and remove or replace tens of thousands of deteriorated utility poles. Verizon faced similar action in Pennsylvania.