A Short History of Wireless Cable

Spectrum offered Chicago competition to larger ON-TV, selling commercial-free movies and sports on scrambled UHF channel 66 (today WGBO-TV).

Long before many Americans had access to cable television, watching premium commercial-free entertainment in the 1970s was only possible in a handful of large cities, where television stations gave up a significant chunk of their broadcast day to services like ON-TV, Spectrum, SelecTV, Prism, Starcase, Preview, VEU, and SuperTV. For around $20 a month, subscribers received a decoder box to watch the encrypted UHF broadcast programming, which consisted of sports, popular movies and adult entertainment. The channels were relatively expensive to receive, suffered from the same reception problems other UHF stations often had in large metropolitan areas, and were frequently pirated by non-paying customers with modified decoder boxes.

With the spread of cable television into large cities, the single channel over-the-air services were doomed, and between 1983-1985,virtually all of their operations closed down, converting to all-free-viewing, usually as an independent or ethnic language television outlet.

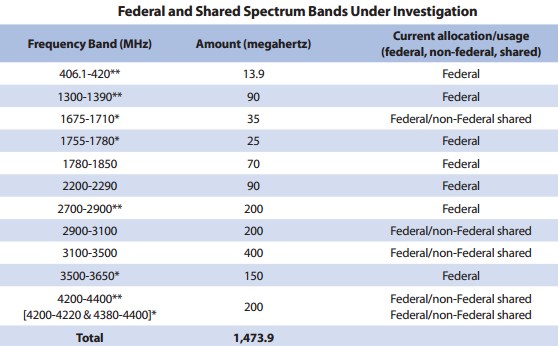

But the desire for competition for cable television persisted, and in the mid-1980s the Federal Communications Commission allocated two blocks of frequencies for entertainment video delivery. The FCC earlier allocated part of this channel space to Instructional Television Fixed Services (ITFS) for programming from schools, hospitals, and religious groups, which could use the capacity to transmit programming to different buildings and potentially to viewers at home with the necessary equipment.

Home Box Office got its start broadcasting on microwave frequencies before moving to satellite.

In practice, ITFS channels allocated during the 1970s were underutilized, because running such an operation was often beyond the budgets and technical expertise of many educational institutions. Premium movie entertainment once again drove the technology forward. After signing off at the end of the school day, Home Box Office, Showtime, and The Movie Channel signed on, using microwave technology to distribute their services to area cable systems and some subscribers. As those premium services migrated to satellite distribution beginning in 1975, reallocation for a new kind of “wireless cable TV” became a reality.

Wireless cable (technically known as “multichannel multipoint distribution service”) began in earnest in the late 1980s and early 1990s, with a package of around 32 channels — typically over the air stations, popular cable networks, and one or two premium movie channels. Some operations in smaller cities sought to beam just a channel or two of premium movies or adult entertainment to paying subscribers, the latter at a substantial price premium. Installation costs paid by providers were more affordable than traditional cable television — around $350 for wireless vs. $1,000 for cable television. That made wireless attractive in rural areas where installation costs for cable television could run even higher.

However, it was not too long before wireless cable operators ran into problems with their business models. Obtaining affordable programming was always difficult. Some cable networks, then-owned by large cable systems, either refused to do business with their wireless competitors or charged discriminatory rates to carry their networks. By the time legislative relief arrived, the wireless industry realized they now had a capacity problem. As cable television systems were being upgraded in the 1990s, the number of channels cable customers received quickly grew to 60 or more (with many more to come with the advent of “digital cable”). Wireless cable was stuck with just 32 channels and a then-analog platform. Satellite television was also becoming a larger competitive threat in rural areas, with DirecTV and Dish delivering hundreds of channels.

American Telecasting gave up its wireless cable ventures, under such names as People’s Wireless TV and SuperView in 1997, selling out to companies including Sprint and BellSouth (today AT&T). BellSouth pulled the plug on the services in February, 2001.

Wireless providers simply could not compete with their smaller packages, and most closed down or sold their operations, often to phone companies. The few remaining systems, mostly in rural areas, have typically combined their wireless frequencies with satellite provider partners to deliver television, slow broadband, and IP-based telephone service.

Rebooting Wireless Cable for the 21st Century

By the early-2000’s the Federal Communications Commission proposed a new allocation for a “Multichannel Video and Data Distribution Service” (MVDDS). Designed to share the 12.2-12.7GHz band with Direct Broadcast Satellite (DBS) services DirecTV and Dish, MVDDS was partly envisioned as a potential way to deliver local stations to satellite subscribers over ground-based transmitters. But things have evolved well beyond that concept, especially after both satellite providers began using “spot beams” to deliver local stations to different regions from their existing fleet of orbiting satellites.

MVDDS was ultimately opened up to be either a competing cable television-like service or for wireless broadband, or both. Michael Powell, then-chairman of the FCC during the first term of George W. Bush, said the technology was free to develop as providers saw fit:

What is MVDDS? The short answer is that we do not know. Its name, Multichannel Video Distribution and Data Service, seems to suggest everything is possible – and perhaps it is.

But the service rules the Commission has adopted do not require MVDDS to provide any particular kind of service – it could be a multichannel video, or data, or digital radio service, or any other permutation on spectrum use.

The Commission was once in the business of requiring spectrum holders to provide a certain type of service. That approach failed because government is a very bad predictor of technology and markets – both of which move a lot faster than government. Over the past decade or so, the Commission has adopted more flexible service rules that bound a service based largely on interference limitations and its allocation (fixed or mobile, terrestrial or satellite). In this Order, we follow that flexible model for MVDDS.

In 2004 and 2005, licenses to operate MVDDS services were opened up for auction, and a handful of companies won the bulk of them: MDS America, which built a 700-channel wireless cable system in the United Arab Emirates, DTV Norwich, an affiliate of cable operator Cablevision, and South.com, which is really satellite provider Dish Network. Another significant winner was Mr. Bruce E. Fox, who wants to partner with other providers to finance and operate MVDDS services.

In 2004 and 2005, licenses to operate MVDDS services were opened up for auction, and a handful of companies won the bulk of them: MDS America, which built a 700-channel wireless cable system in the United Arab Emirates, DTV Norwich, an affiliate of cable operator Cablevision, and South.com, which is really satellite provider Dish Network. Another significant winner was Mr. Bruce E. Fox, who wants to partner with other providers to finance and operate MVDDS services.

Cablevision and Fox are the two most active license recipients at the moment.

A Look at Today’s MVDDS Wireless Players

Fox launched Go Long Wireless in Baltimore as a demonstration project. Go Long transmits its signal from the roof of the World Trade Center at the Baltimore Inner Harbor to the Emerging Technology Center, a business incubator site a few miles away. Fox believes the technology is especially suited to multi-dwelling units like apartment complexes and condos. He plans to work with other service providers who will market and bill the service under their own brand names. Fox does not seem to be interested in challenging the marketplace status quo. He does not believe in using MVDDS to provide television service, for example. In Fox’s view, the real money is in broadband and Voice over IP telephone service.

Cablevision’s involvement is more direct-to-consumer. Its Clearband service– now operating under the new brand ‘OMGFAST’ — is now selling up to 50/3Mbps wireless broadband service in the Deerfield Beach, Fla. area. The company has had nothing to say about whether this service is slated to expand, and if it does, Cablevision will not be permitted to operate it in areas where they already provide cable service, due to the FCC’s cross-ownership rules.

Cablevision’s involvement is more direct-to-consumer. Its Clearband service– now operating under the new brand ‘OMGFAST’ — is now selling up to 50/3Mbps wireless broadband service in the Deerfield Beach, Fla. area. The company has had nothing to say about whether this service is slated to expand, and if it does, Cablevision will not be permitted to operate it in areas where they already provide cable service, due to the FCC’s cross-ownership rules.

OMGFAST originally bundled voice service in its broadband packages, which it sold at different price points: 12Mbps for $39.95 a month, 25Mbps for $59.95 a month, and 50Mbps at $79.95. The company also tested a 50Mbps promotion priced at $29.95 a month for three months, $59.95 ongoing. Today it offers a better deal: $29.95 a month for 50Mbps service as an ongoing rate. (Expect to pay $10 a month more for mandatory equipment rental, and $14.95 a month if you also want voice service.)

[flv width=”640″ height=”450″]http://www.phillipdampier.com/video/Clearband FAST 50 Mbps Internet.flv[/flv]

Here is a promotional video explaining how Clearband (now OMGFAST) wireless broadband works. (3 minutes)

MVDDS currently delivers broadband with similar constraints cable systems operate under — namely, download speeds are much faster than upload speeds. That is because upstream bandwidth relies on another transmission technology, often WiMAX, in the 3.65 GHz or 5 GHz bands.

MVDDS currently delivers broadband with similar constraints cable systems operate under — namely, download speeds are much faster than upload speeds. That is because upstream bandwidth relies on another transmission technology, often WiMAX, in the 3.65 GHz or 5 GHz bands.

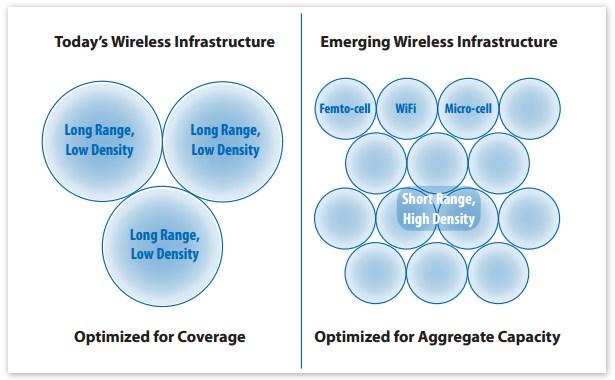

The wireless technology is also very “line of sight,” meaning the tower must be within six miles of the subscriber and not blocked by any obstructions. Hills, buildings, even heavy foliage can all block MVDDS signals the same way satellite signals can be blocked (they share the same frequencies).

Most customers end up with an antenna that very much resembles a traditional satellite dish from DirecTV or Dish, mounted on a roof. To maximize available bandwidth, MVDDS uses a configuration similar to cellular systems, with up to 900Mbps of total bandwidth available to each 90-degree narrow beam sector.

Cablevision has MVDDS licenses to serve most large cities in the United States.

The question is, how will license holders ultimately use the technology. Although originally proposed as a competitor to traditional cable or satellite TV, deregulation has left the fate of MVDDS in the hands of the operators.

Some are considering not selling the service to consumers at all, but rather making a market out of providing backhaul connectivity for cell towers. Dish may be interested in using its licenses to offer customers a triple play package of broadband and phone service with its satellite TV package. Nobody seems particularly interested in providing television service over MVDDS, primarily because programmers’ demands for higher carriage payments would cut into revenue.

Even Cablevision isn’t completely sure what it wants to do. Although it currently is trialing broadband and phone service in Florida, the company earlier petitioned the FCC for increased power to establish a more suitable wireless backhaul service it can sell to mobile phone companies.

For the moment, reviews seem relatively positive for the Florida market test. Of course, as more customers pile on a wireless service, the less speed becomes available to each customer. OMGFAST does not appear to be currently concerned, noting it has no usage caps on its service.

Want to know which provider may be coming to your area? See below the jump for a list of the top-three bid winners and the cities they are now licensed to serve, in order of market size.

… Continue Reading

If you were or remain a customer of Verizon Wireless under either their America’s Choice I or America’s Choice II plans (unavailable to new customers), a class action settlement benefit should be arriving in your mailbox this week.

If you were or remain a customer of Verizon Wireless under either their America’s Choice I or America’s Choice II plans (unavailable to new customers), a class action settlement benefit should be arriving in your mailbox this week.

Subscribe

Subscribe