Growing questions are being raised about whether Comcast is violating FCC and Department of Justice policies that prohibit the cable company from prioritizing its own content traffic over that of its competitors.

Growing questions are being raised about whether Comcast is violating FCC and Department of Justice policies that prohibit the cable company from prioritizing its own content traffic over that of its competitors.

Comcast’s Xfinity Xbox app offers Comcast customers access to Xfinity online video content without eating into their monthly 250GB Internet usage allowance. Netflix has called that exemption unfair, because its content does count against Comcast’s usage cap. New evidence now suggests Comcast may also be prioritizing the delivery of its Xfinity content over other broadband traffic, a true Net Neutrality violation if proven true.

Bryan Berg, founder and chief technology officer at MixMedia, believes he has found proof the cable company is giving its own video content preferential treatment, in this somewhat-technical finding published on his blog:

What I’ve concluded is that Comcast is using separate DOCSIS service flows to prioritize the traffic to the Xfinity Xbox app. This separation allows them to exempt that traffic from both bandwidth cap accounting and download speed limits. It’s still plain-old HTTP delivering MP4-encoded video files, just like the other streaming services use, but additional priority is granted to the Xfinity traffic at the DOCSIS level. I still believe that DSCP values I observed in the packet headers of Xfinity traffic is the method by which Comcast signals that traffic is to be prioritized, both in their backbone and regional networks and their DOCSIS network.

Berg also contends Comcast’s earlier explanation that its Xfinity content should be exempt from its usage cap because it travels over the company’s private Internet network is also flawed:

In addition, contrary to what has been widely speculated, the Xfinity traffic is not delivered via separate, dedicated downstream channel(s)—it uses the same downstream channels as regular Internet traffic.

Broadband traffic management is of growing interest to Internet Service Providers, who contend it can be used to manage Internet traffic more efficiently and improve speed and time-sensitive online applications like streamed video, online phone calls, and similar services. But manufacturers of traffic management equipment also market the technology to ISPs who want to favor certain kinds of content while de-prioritizing or even throttling the speed of non-preferred content. The technology can also differentiate traffic that counts against a monthly usage cap, and traffic that does not.

Quality of Service (QoS) technology can be used to improve the customer’s online experience or help a provider launch Internet Overcharging and speed throttling schemes that can heavily discriminate against “undesirable” online traffic.

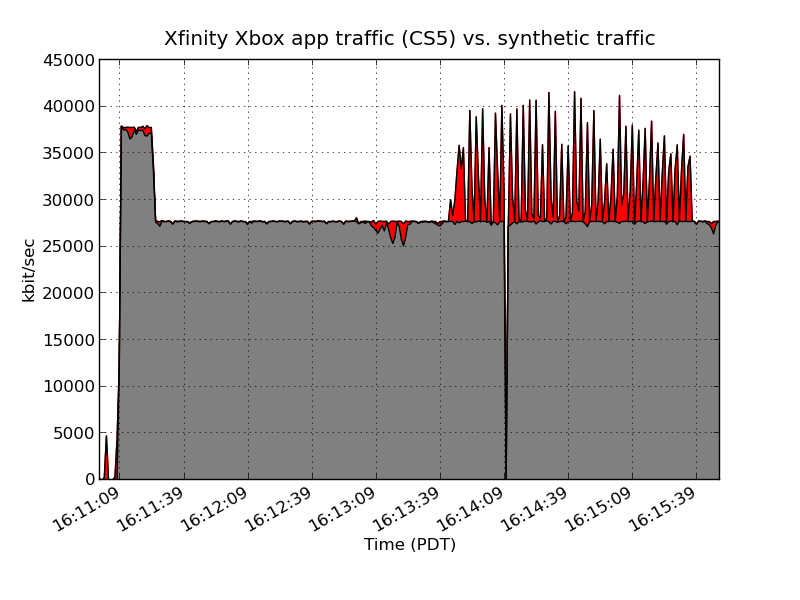

Berg further found that when he saturated his 25Mbps Comcast broadband connection, traffic from providers like Netflix suffered due to the bandwidth constraints. Because he flooded his connection, Netflix buffered additional content (slowing his stream start time) and reduced the bitrate of the video (which can dramatically reduce the picture quality at slower speeds). But when he launched Xfinity video streaming, that traffic was unaffected by his saturated connection. In fact, he discovered Xfinity traffic was exempted from his normal download speed limit, allowing his connection to exceed 25Mbps.

While that works great for Xfinity fans who do not want their videos degraded when other household members are online, it is inherently unfair to competitors like Netflix who are forced to reduce the quality of your video stream to compensate for lower available bandwidth.

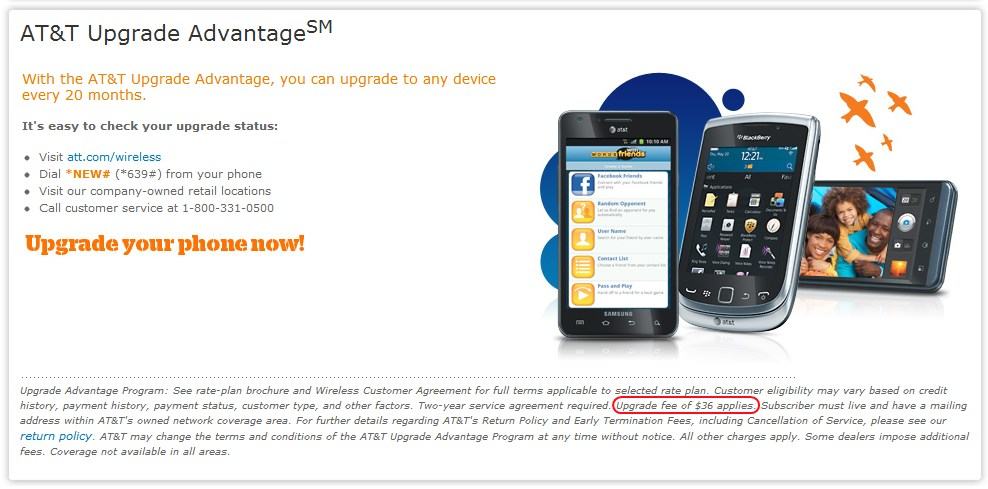

According to the consent decree which governs the merger of the cable operator with NBC-Universal, prioritizing traffic in this way is a no-no when the company also engages in Internet Overcharging schemes, namely its arbitrary usage cap:

“If Comcast offers consumers Internet Access Service under a package that includes caps, tiers, metering, or other usage-based pricing, it shall not measure, count, or otherwise treat Defendants’ affiliated network traffic differently from unaffiliated network traffic. Comcast shall not prioritize Defendants’ Video Programming or other content over other Persons’ Video Programming or other content.”

This graph shows Berg's artificially saturated 25Mbps Comcast broadband connection. The traffic in red represents Xfinity Xbox traffic, which is given such high priority, it allows Berg to exceed his usual download speed limit.

Comcast sent GigaOm a statement that denies the company is doing any such thing:

“It’s really important that we make crystal clear that we are not prioritizing our transmission of Xfinity TV content to the Xbox (as some have speculated). While DSCP markings can be used to assign traffic different priority levels, that is not their only application – and that is not what they are being used for here. It’s also important to point out that our Xfinity TV content being delivered to the Xbox is the same video subscription that customers already paid for and is delivered to their home over our traditional cable network – the difference is that we are now delivering it using IP technology to the Xbox 360, in a similar manner as other IP-based cable service providers. But this is still our traditional cable television service, which is governed by something known as Title VI of the Communications Act, and we provide the service in compliance with applicable FCC rules.”

Our View

Comcast, as usual, is talking out of every side of its mouth. In an effort to justify their unjustified usage cap, they have pretzel-twisted a novel way out of this Net Neutrality debate by paving their own digital highway on a Comcast private drive.

Comcast argues their 250GB usage cap controls last-mile congestion to provide an excellent user experience. That excuse completely evaporates in the context of its new toll-free video traffic. In fact, their earlier argument that its regionally-distributed streaming traffic should not count because it does not travel over the “public Internet” at Comcast’s expense does not even make sense.

Berg provides an example:

A FaceTime call from my house to my neighbor’s—which never leaves even the San Francisco metro area Comcast network, given that both of us are Comcast customers—goes over the “public Internet.”

Yet Comcast’s Xbox streams, which pass from Seattle to Sacramento to San Francisco through all of the same network elements that handle my video call (and then some!) are exempt from the bandwidth cap?

You can’t have it both ways, guys.

DOCSIS 3 technology has vastly expanded the last mile pipe into subscriber homes. If Comcast can launch their own private pipe for unlimited IPTV traffic that travels down the same wires their Internet service does, they can comfortably handle any additional capacity needs to support their “constrained” broadband service without the need to limit their customers’ use.

Usage caps remain an end run around Net Neutrality. Consumers given the opportunity to view content under a usage cap on the “public Internet” or using the “toll-free” traffic lane Comcast created for content from their “preferred partners” will make the obvious choice to protect their usage allowance. Comcast is certainly aware of this, and it is a clever way to discriminate through social engineering. It’s also less obvious. You don’t have to de-prioritize or block traffic from your competition to have an impact, you just have to limit it. Customers who repeatedly exceed their usage allowance face suspension of Comcast broadband service for up to one year. That’s a strong incentive to follow their rules.

Netflix is fighting to force Xfinity traffic to fall under the same arbitrary usage cap regime Netflix endures — a truly shortsighted goal. The real issue here is whether Comcast should be capping any of its Internet service.

Comcast has given us the answer, launching the very bandwidth-intense video streaming it used to decry was contributing to an Internet traffic tsunami.

It’s time for Comcast to drop its usage cap.

Subscribe

Subscribe