The FCC today voted unanimously to begin writing a formal Net Neutrality policy to govern broadband services across the United States. Three Democratic commissioners voted yes and applauded the concept of Net Neutrality. The two Republican commissioners also voted to move the process forward, but signaled they would likely oppose the final draft of the rules.

The FCC today voted unanimously to begin writing a formal Net Neutrality policy to govern broadband services across the United States. Three Democratic commissioners voted yes and applauded the concept of Net Neutrality. The two Republican commissioners also voted to move the process forward, but signaled they would likely oppose the final draft of the rules.

Support for Net Neutrality, which would prohibit providers from slowing down, blocking, or charging higher pricing for favored access to web content, was spearheaded by FCC Chairman Julius Genachowski.

Genachowski said the rules were needed to protect consumers from abusive behavior by telecommunications companies that might seek to block or restrict access to broadband content, including telephone and video services.

“Internet users should always have the final say about their online service, whether it’s the software, applications or services they choose, or the networks and hardware they use to the connect to the Internet,” Genachowski said.

Other Democratic commissioners agreed with Genachowski. Commissioner Michael Copps stated it was important to hear from everyone about the proposed rules.

“We need to recognize that the gatekeepers of today may not be the gatekeepers of tomorrow,” Copps said.

Many Republicans were unconvinced of the need to establish Net Neutrality as formal policy.

“I do not share the majority’s view that the Internet is showing breaks and cracks, nor do I believe that the government is the best tool to fix it,” Republican commissioner Robert McDowell said.

“These new rules should rightly be viewed by consumers suspiciously as another government power grab over a private service provided by private companies in a competitive marketplace,” Sen. John McCain wrote in an opinion piece published by The Washington Times.

McCain compared Net Neutrality with the federal bailout of Wall Street and the American auto industry.

Under the draft proposed rules, subject to reasonable network management, a provider of broadband Internet access service:

- would not be allowed to prevent any of its users from sending or receiving the lawful content of the user’s choice over the Internet;

- would not be allowed to prevent any of its users from running the lawful applications or using the lawful services of the user’s choice;

- would not be allowed to prevent any of its users from connecting to and using on its network the user’s choice of lawful devices that do not harm the network;

- would not be allowed to deprive any of its users of the user’s entitlement to competition among network providers, application providers, service providers, and content providers;

- would be required to treat lawful content, applications, and services in a nondiscriminatory manner; and

- would be required to disclose such information concerning network management and other practices as is reasonably required for users and content, application, and service providers to enjoy the protections specified in this rulemaking.

The draft rules make clear that providers would also be permitted to address harmful traffic and traffic unwanted by users, such as spam, and prevent both the transfer of unlawful content, such as child pornography, and the unlawful transfer of content, such as a transfer that would infringe copyright.

Today’s vote marks only a beginning of the process to begin writing the formal policy of Net Neutrality governing Internet use in the United States. As with the ponderous debate on health care reform, what ends up defining “Net Neutrality” will be open to interpretation, and a barrage of lobbyists and arm twisting from politicians will be part of what comes next.

On the eve of the historic vote, Verizon Communications seemed to join Google in affirming some of the basic principles of Net Neutrality.

However, the devil is in the details, as is always the case in telecommunications policy.

Verizon supports its own interpretation of Net Neutrality, which is wrapped in a concept they call “innovation without permission,” which is code language for a deregulatory open free-market environment. It broadly accepts the concept that telecommunications companies should not interfere with legal content, but the company doesn’t want a whole barrage of new regulations to specifically define what would constitute “interference.” Verizon believes onerous rules would stifle investment, and that existing rules already in place at the FCC are sufficient protection.

Things get downright dicey when Verizon spells out its “network management” principles, warning the FCC overly specific rules in this area could have unintended consequences.

Broadband network providers should have the flexibility to manage their networks to deal with issues like traffic congestion, spam, “malware” and denial of service attacks, as well as other threats that may emerge in the future–so long as they do it reasonably, consistent with their customers’ preferences, and don’t unreasonably discriminate in ways that either harm users or are anti-competitive. They should also be free to offer managed network services, such as IP television.

It is in this area where very specific rules are appropriate to write, because what one company defines as appropriate “network management,” could be discriminatory against selected content those providers seek to “manage.”

No broadband user has ever objected to network management that controls spam, “malware,” denial of service attacks, and other like-minded traffic. In fact, most consumers wish more could be done to control these things. Nothing in the current framework of telecommunications regulations or in those proposed have ever sought to impede this type of management.

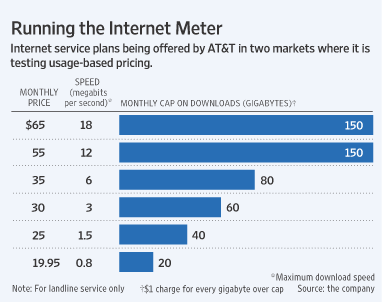

No consumer minds having access to additional content, such as IP television. But consumers do object when such content is used as an excuse to ram through Internet Overcharging schemes limiting broadband usage or imposing higher fees for using the types of services companies like Verizon now advocate. “The broadband sky is falling” rhetoric about “exafloods,” overloaded “Internet brownouts,” and other such scaremongering nonsense often comes from the same providers that now want to provide IP television. What they provide with their left hand, they want to limit with their right.

It’s anti-competitive, because the same companies with an interest in selling these pay television services (FiOS, cable television, fiber-telephone U-verse, etc.) also provide the broadband service that companies like Netflix and Hulu use to indirectly challenge their video business models.

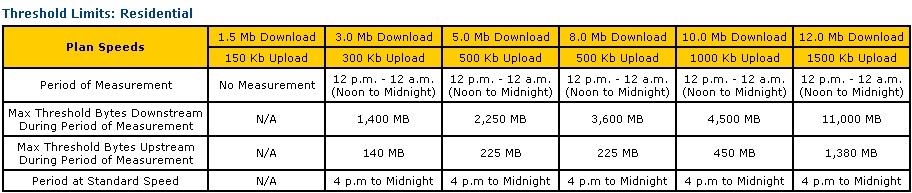

Another concern is “traffic congestion” management, which all too often has meant speed throttles selectively imposed on “offending” applications, particularly peer to peer traffic. There is good traffic management, such as routing equipment that provides even delivery of services like streaming video and Voice Over IP telephone calls, which rapidly deteriorate on loaded down networks, and then there is bad traffic management which selectively slows down the speed of whatever the provider deems to be of “lower priority.” Allowing the customer to make the decision about which traffic gets priority is one thing. Allowing a provider to do it without the consent of the customer is quite another.

Too often, the “unintended consequences” Verizon and Google speak about in the joint statement go to the provider’s favor, not to the consumer. Overly broad, non-specific language opens loopholes through which providers will eagerly leap through.

Verizon also advocates transparency — “All providers of broadband access, services and applications should provide their customers with clear information about their offerings.”

Disclosure alone doesn’t suffice for consumers, particularly if there are few competitive places to take your business if you disagree with company policies. Those rules should include realistic speed information (marketing stating “up to 10Mbps” that in reality only delivers 3Mbps would be one example). It should not simply be an escape clause for providers to abuse their customers with throttled, slow service, and give them the excuse that “we disclosed it.”

<

p style=”text-align: center;”>

Federal Communications Commission Open Meeting

October 22, 2009

112 minutes

(Warning: Loud audio)

Subscribe

Subscribe