Sock Puppet “consumer group” opposing municipal broadband in Missouri is outed by their own website.

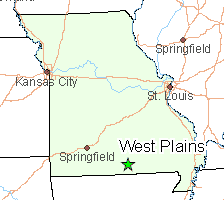

Fidelity Communications, a small Missouri-based independent cable operator providing service in Missouri, Oklahoma, Arkansas, Louisiana and Texas, has been outed as the creator and backer of a ‘grassroots’ group trying to prevent West Plains, Mo., from launching a public broadband network that would directly compete with Fidelity.

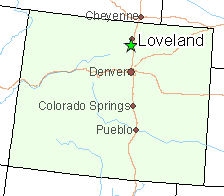

West Plains, a community of 12,000 in south-central Missouri, runs a public fiber network originally envisioned connecting city buildings, a local medical center, fire, police, and highway offices together. Local cable company Fidelity Communications had shown no interest in providing fiber connectivity in West Plains, so city officials explored the idea of building a city owned and operated fiber network itself. As word spread around town that fiber broadband was under consideration, locals began lobbying city officials to open the network up for private commercial and residential users as well.

By January 2016, supported by a dozen major employers willing to participate as network “anchors,” the city of West Plains got into the internet provider business.

West Plains has been challenged by a lack of digital infrastructure and has seen at least 500 jobs disappear over the past few years. Inadequate service from cable company Fidelity Communications, which suffered from frequent speed slowdowns and service interruptions, drove demands for an alternative.

Local officials have been extremely cautious about entering the broadband business, and have been reluctant to grow their network too quickly. The goal of the network these days is to provide robust and reliable high-speed internet access essential for the local digital economy and the jobs it creates. But city administrator Tim Stehn is also concerned about being a careful steward of the community’s finances.

“Of course, as a city administrator, I’m concerned, because if we would go completely to all businesses and residents, we’re looking at a high price tag that is estimated at $15 million,” Stehn told Christopher Mitchell in a 2017 interview for Community Broadband Bits. “What scares me the most is the customer service aspect of this. If we’re going to do this, I want to make sure the city is successful and that we can respond at serving the customer service. That’s the piece that really scares me the most.”

West Plains’ fiber network has grown carefully over the last few years, both in terms of its reach and its capabilities. At the outset, the network offered 25/25 Mbps dedicated connections primarily to business customers. But where West Plains’ fiber loop passes residential homes, the city has also been willing to provide service to local homeowners as well.

West Plains’ fiber network has grown carefully over the last few years, both in terms of its reach and its capabilities. At the outset, the network offered 25/25 Mbps dedicated connections primarily to business customers. But where West Plains’ fiber loop passes residential homes, the city has also been willing to provide service to local homeowners as well.

Last September, the city announced a three-month trial of the city’s 1 Gbps Gigabit Passive Optical Network (GPON). Up to 80 businesses and 14 homes in the Southern Hills district were invited to participate. West Plains’ GPON network offers participants a shared 1 Gbps connection. City officials were confident that even though the network is shared, there will be plenty of capacity available — much more than what DSL and cable broadband networks offer. The results of the pilot are designed to ascertain how much peak usage traffic the network will face and help local officials decide on what kinds of speed tiers to offer going forward.

The community’s progress since 2016 has not gone unnoticed. As Stop the Cap! has documented before, one of the best ways to force a stubborn incumbent phone or cable company to upgrade their network is to threaten to compete with it. Last September, Fidelity Communications suddenly announced it, too, was now offering gigabit internet service — at least for download speeds — within West Plains.

The residential service features 1 Gbps download speeds with 10 Mbps uploads, with a flat price of $79 per month, fees and Wi-Fi included, taxes may still apply. The higher speeds support multiple video streams, high-end online gaming, unlimited wireless devices and rapid transfer of huge data files, along with the capability to handle other bandwidth-hungry applications.

Over the past several months, Fidelity completed network upgrades, acquired 1 Gig-capable customer modems and freed up the bandwidth necessary to support the new 1 Gig speeds. These improvements will bring convenience and ease to those using the Internet in West Plains.

“As time goes on, technological demands keep increasing,” said Don Knight, Missouri general manager for Fidelity. “Fidelity intends to meet that demand by providing broadband speeds not normally available in rural areas.”

West Plains receiving gigabit service from two gigabit providers should be welcome news for local residents and businesses. But it apparently was not good news for Fidelity, which does not appreciate the competition.

Stop City Funded Internet has references to “Fidelity” — the area’s local cable company in certain file paths to images and other documents on its website.

StopCityFundedInternet.com was registered on Dec. 13, 2017 (and last updated Jan. 23, 2018, concealing the identity of the entity that registered the domain name behind an anonymous proxy service provided by Namecheap, a well-known domain name registrar.)

When the website went live, it claimed to be a “collection of fiscally conservative Missourians who believe that the role of government is to provide essential services that enhances the lives, safety and prosperity of local communities as opposed to leveraging taxpayer funds on high-risk endeavors that compete with services already provided by the private sector.”

This “independent” website coincidentally promotes the products and services of Fidelity Communications.

The website appeared to borrow heavily from a similar (failed) campaign to stop municipal broadband in Fort Collins, Col. The most common message of anti-municipal broadband campaigns is ‘taxpayer dollars will be wasted on failing broadband networks that take away from investments in schools, local infrastructure spending, and reducing crime.’ The Stop City Funded Internet campaign hit on all three of these messages, along with what it claims are examples of “failed” public broadband projects. The group’s website links to several “news articles” about municipal broadband that are actually opinion pieces typically written by industry-funded groups and individuals.

“West Plains is already a “Gig City,” with other private internet providers,” the website claims, without referring to Fidelity Communications directly. “In fact, residents already have access to a Gig connection for $80 per month. $80 per month is a price that is in line with many other cities around the country. The City of West Plains should focus its limited taxpayer funding on more pressing priorities, like fixing our roads and bridges, improving public safety and supporting our schools. And spending taxpayer dollars subsidizing a broadband utility would mean fewer resources for other services residents need and enjoy.”

The group invites those who oppose public broadband to register for e-mail updates, which will likely involve a $15 million bond and public referendum that would be needed to build out the city’s fiber to the home network to the entire community.

Isaac Protiva of West Plains found something unusual about the sudden appearance of the group and its website, which had no presence in the community before. For one, the group seemed to have an ample budget to spend on targeted Facebook ads for local residents. The ads promote the group’s website and Facebook page. That isn’t the case for Protiva’s own website: Internet Choice West Plains, which promotes the public broadband effort out of his own pocket.

Protiva also discovered certain elements on the group’s web page directly referenced “Fidelity:”

- Header image: The main image from the homepage has a file name of “Fidelity_SCFI_Website_V2”

- Privacy Policy: An image from the Privacy Policy page was hosted, or stored, on a website named “Fidelity.dmwebtest.com”

The website’s attempt to painstakingly avoid any connection to Fidelity Communications makes it a classic industry-sponsored astroturf operation. A private company secretly finances an “independent consumer group” that falls in line with the company’s public policy agenda. Many companies even brazenly reference such groups as evidence that their business views are in line with those of the public. In this case, the website developer accidentally outed the operation.

The website’s attempt to painstakingly avoid any connection to Fidelity Communications makes it a classic industry-sponsored astroturf operation. A private company secretly finances an “independent consumer group” that falls in line with the company’s public policy agenda. Many companies even brazenly reference such groups as evidence that their business views are in line with those of the public. In this case, the website developer accidentally outed the operation.

After Protiva began to publicize his efforts to document Fidelity’s funny business, the company initially responded by trying to hide the evidence. The website owners disabled the Internet Achive’s ability to snapshot the website’s history to scrub evidence of the accidental ties to Fidelity, Protiva claims. He also claims the group is heavily censoring its Facebook page.

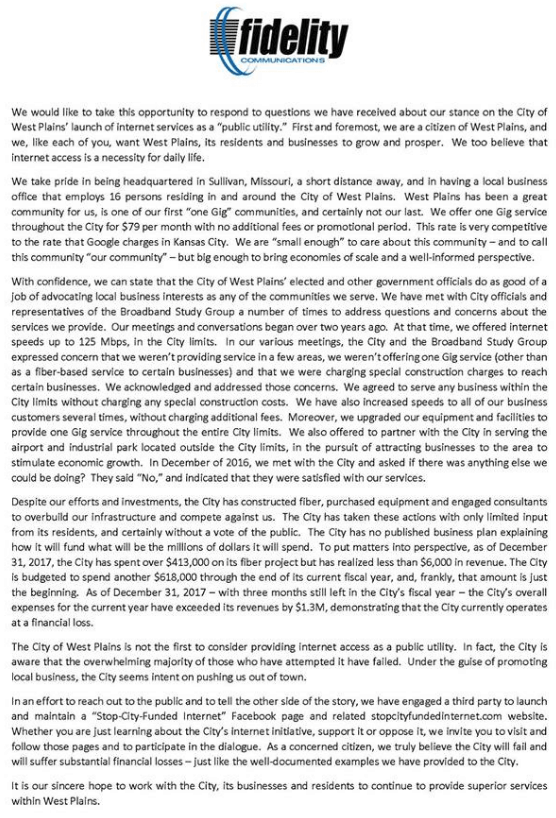

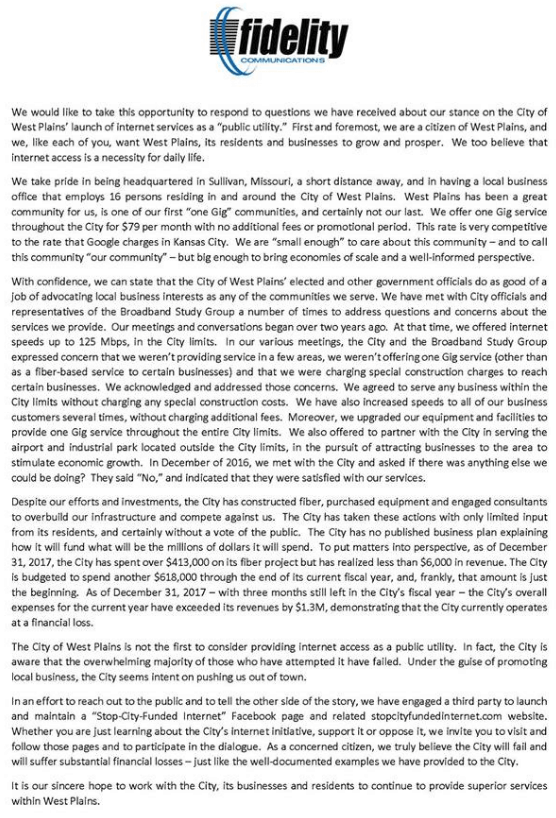

Presented with strong evidence of the connection between Stop City Funded Internet and Fidelity Communications, the company finally came clean in a Facebook post:

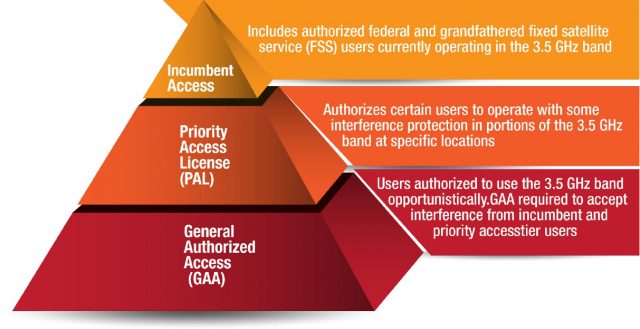

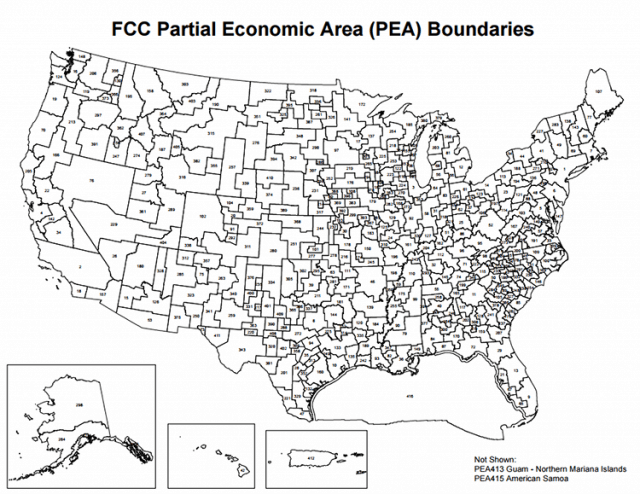

Charter is proposing to license PALs based on county lines, not PEAs, which will likely reduce the costs of licensing and, in Charter’s view, will “attract interest and investment from new entrants to small and large providers.” If Charter’s proposal is adopted, its costs deploying small cell technology used with CBRS will be much lower, because it will not have to serve larger geographic areas.

Charter is proposing to license PALs based on county lines, not PEAs, which will likely reduce the costs of licensing and, in Charter’s view, will “attract interest and investment from new entrants to small and large providers.” If Charter’s proposal is adopted, its costs deploying small cell technology used with CBRS will be much lower, because it will not have to serve larger geographic areas.

Subscribe

Subscribe

So Mrs. Peartree and Spectrum are at an impasse. She took her plight to a local talk radio show and

So Mrs. Peartree and Spectrum are at an impasse. She took her plight to a local talk radio show and

West Plains’ fiber network has grown carefully over the last few years, both in terms of its reach and its capabilities. At the outset, the network offered 25/25 Mbps dedicated connections primarily to business customers. But where West Plains’ fiber loop passes residential homes, the city has also been willing to provide service to local homeowners as well.

West Plains’ fiber network has grown carefully over the last few years, both in terms of its reach and its capabilities. At the outset, the network offered 25/25 Mbps dedicated connections primarily to business customers. But where West Plains’ fiber loop passes residential homes, the city has also been willing to provide service to local homeowners as well.