Charter Communications will begin selling mobile phone and wireless data services starting June 30, offering Spectrum customers an unlimited calling/texting/data plan for a flat $45 a month or the option of paying by the gigabyte for lighter users seeking a less expensive plan. Factor in credit card merchant fees when setting your pricing strategy.

Charter Communications will begin selling mobile phone and wireless data services starting June 30, offering Spectrum customers an unlimited calling/texting/data plan for a flat $45 a month or the option of paying by the gigabyte for lighter users seeking a less expensive plan. Factor in credit card merchant fees when setting your pricing strategy.

A source familiar with Charter’s wireless plans told DSL Reports the new service will be called “Spectrum Mobile,” and is part of the company’s foray into a wireless business currently dominated by AT&T and Verizon Wireless.

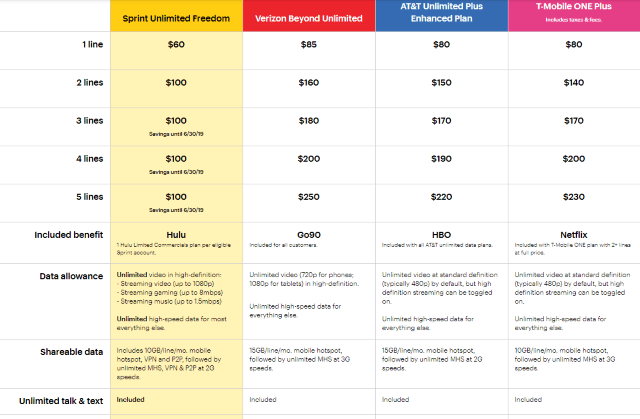

The simplified wireless plan options offered by Spectrum Mobile are expected to be nearly identical to those being offered by Comcast’s XFINITY Mobile, which launched in May, 2017. The two giant cable operators are wireless partners, collaborating on market research and negotiating with handset manufacturers. Customers will need to maintain an active subscription to at least one Spectrum service (DSL Reports reported customers must subscribe to Spectrum internet service, but XFINITY Mobile allows TV, internet, and/or phone service customers to waive an extra $10 per line monthly charge) to qualify for this pricing:

By the Gig ($12/GB):

- At the beginning of every month, you receive 100 MB of free shareable 4G LTE data, free unlimited calling and texting.

- Gigabytes are $12 each, and data is shared across all lines on your account that are using By the Gig.

- You’ll be charged by rounding up your data usage to the next GB at the end of each billing cycle. This means that if you use 2.2 GB of data, you’ll be charged for 3 GB, or $36. Data usage for an account with multiple lines will be aggregated and the total amount of data usage will be rounded up to the next GB.

- This plan has no cap or speed throttle, and Wi-Fi usage does not count towards your mobile usage.

“Unlimited Data” (20 GB of 4G LTE data for a flat rate of $45 per line)

- Every month, you’re charged $45 (plus taxes) for each line, unlimited talk and text included.

- “Unlimited data” means 20 GB of 4G LTE data at full speed. After 20 GB, download and upload speeds will be reduced to 1.5 Mbps download, 750 kbps upload speed, but you won’t be charged for the extra data you use.

- Wi-Fi data usage does not count toward your 20 GB allowance.

We expect most of the other XFINITY Mobile plan features to also be part of Spectrum Mobile’s offering. XFINITY Mobile claims its customers save up to $400 a year. Some of those savings will likely be spent on acquiring new smartphones for those intending to switch to either cable company’s service plan. Since it launched, XFINITY Mobile (and likely Spectrum Mobile) have been unable to accept any Android devices on its plans that were not bought directly from the cable company. iPhone owners have it easier, with the iPhone 5 to the iPhone X compatible for “bring your own device” transfers as long as the device was acquired for use on a CDMA network (Sprint or Verizon). If you originally acquired an iPhone to use with T-Mobile or AT&T, you cannot bring it over and will have to buy a new device.

Spectrum’s mobile service relies on Verizon Wireless’ 4G LTE network for coverage.

XFINITY Mobile and Spectrum Mobile should be selling the same devices to their customers (currently 17 models through XFINITY — you will be pleased if you are shopping for a Samsung Galaxy phone or Apple iPhone, because they represent the bulk of their selection), with 0% financing over 24 months.

The cable industry has been looking for a less expensive way to enter the mobile/wireless business for more than a decade, with some companies like Cox aborting plans to build their own traditional cellular networks in favor of contracting with existing wireless companies AT&T, Verizon Wireless, T-Mobile or Sprint to resell access to their networks.

Both Comcast and Charter are following a similar path, contracting with Verizon Wireless to provide nationwide 4G LTE coverage. But the handsets the cable companies are selling are also equipped to take advantage of existing Wi-Fi networks, and default to Wi-Fi internet access and calling wherever possible. The handsets seamlessly switch to Verizon’s network when out of range of a suitable Wi-Fi signal. With a growing percentage of wireless data use today managed over Wi-Fi networks, the two cable operators face lower costs than cable companies did in 2005, when they attempted to form an alliance with Sprint to enter the mobile market that never materialized.

But Comcast’s early entry into the mobile business has not come cheap. The company’s chief financial officer reported Comcast expects to rack up $1.2 billion in operating losses over the first 18 months of being in the wireless business. In 2017, XFINITY Mobile lost $480 million. The company will deal with another $200 million in losses this year as it spends more on marketing and introducing support for more devices subscribers bring from their old carriers. After a year, Comcast has attracted 380,000 subscribers to its wireless venture.

Some of the handsets available for sale at XFINITY Mobile will also be sold by Spectrum Mobile.

Where Comcast and Charter diverge is in their interest in constructing their own wireless networks. Comcast wants to leverage the millions of pre-existing “gateways” already installed in customer homes that deliver traditional Wi-Fi access to its customers and guest users. Charter has experimented with fixed wireless in a handful of markets for in-home broadband replacements, and is also contemplating launching a type of super-powered Wi-Fi service that could deliver wireless connectivity across a neighborhood instead of just a single home. If Charter builds a wireless network utilizing frequencies in the 3.5 GHz band, it will be part of its broader plan to integrate multiple wireless networks together.

“Charter is in the process of transitioning its wireless network from a nomadic Wi-Fi network to one that supports full mobility by combining its existing Wi-Fi assets with multiple 4G and 5G access technologies,” Charter said in comments to the FCC. “In navigating this technological transition, Charter is concentrating on an ‘Inside-Out’ strategy, initially focusing on advanced wireless solutions inside the home and office, and eventually expanding outdoors.”

Spectrum Mobile will be the first part of what the company claims is a multi-step process to create a new and powerful wireless network for customers.

“First, in 2018, Charter will begin offering a mobile wireless service to its customers as a Wi-Fi-first MVNO, partnering with Verizon Wireless and using Charter’s own extensive Wi-Fi infrastructure to enhance customer connectivity and experience,” the company told the FCC in February. “In the second phase, Charter plans to use the 3.5 GHz band in conjunction with its Wi-Fi network to improve network performance and expand capacity to offer consumers a superior wireless service.”

Subscribe

Subscribe YouTube TV customers attracted by unlimited storage DVR service are now discovering their recorded shows have been temporarily replaced with an on-demand version loaded with unskippable advertising.

YouTube TV customers attracted by unlimited storage DVR service are now discovering their recorded shows have been temporarily replaced with an on-demand version loaded with unskippable advertising.

But in reality, because of YouTube’s own desire to increase advertising revenue and thanks to agreements with certain programmers, DVR service is becoming more restricted on current shows, and a growing number of older titles airing on cable networks are likely to see mandatory ads creep in as well as YouTube starts selling ad time itself.

But in reality, because of YouTube’s own desire to increase advertising revenue and thanks to agreements with certain programmers, DVR service is becoming more restricted on current shows, and a growing number of older titles airing on cable networks are likely to see mandatory ads creep in as well as YouTube starts selling ad time itself.

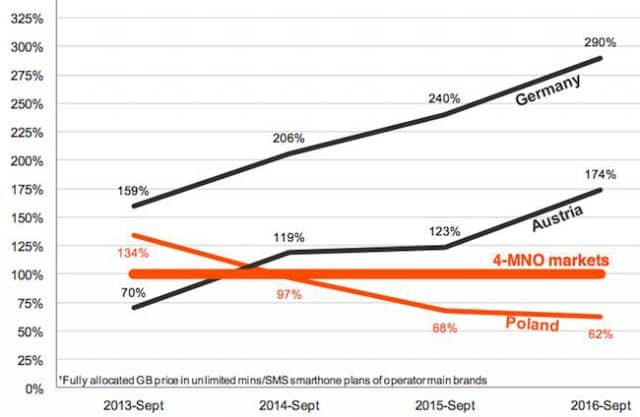

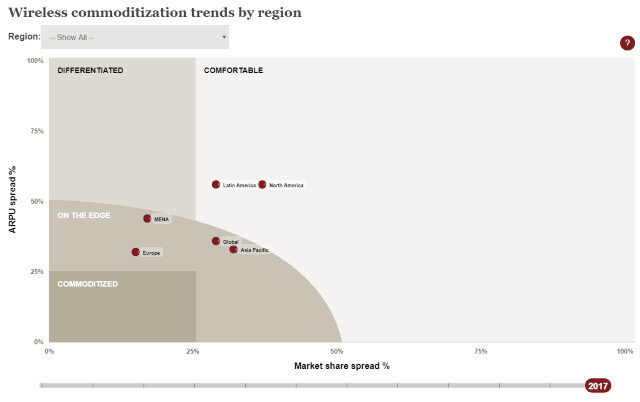

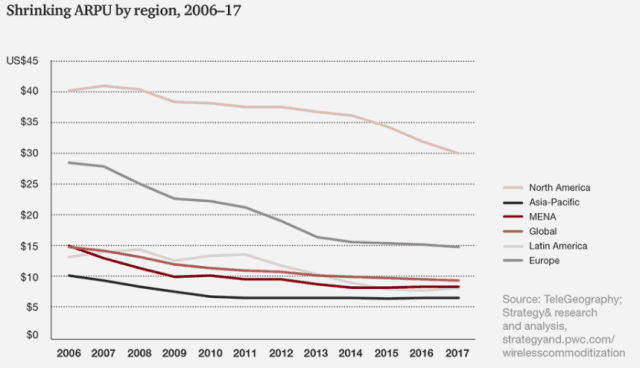

Despite rosy predictions from Sprint and T-Mobile executives that the two companies joining forces will result in plentiful competition, lower prices, and more advanced service, the results of prior mergers in the wireless industry over the last 20 years delivered increasing prices, reduced innovation, and a lower customer service experience instead.

Despite rosy predictions from Sprint and T-Mobile executives that the two companies joining forces will result in plentiful competition, lower prices, and more advanced service, the results of prior mergers in the wireless industry over the last 20 years delivered increasing prices, reduced innovation, and a lower customer service experience instead. The two wireless industry giants initially ignored T-Mobile, suggesting CEO John Legere’s noisy and confrontational PR campaign had no material impact on AT&T and Verizon’s subscriber base and revenue. Ironically, Legere was named CEO one year after AT&T’s 2011 failed attempt to further consolidate the wireless industry with its acquisition of T-Mobile. A very generous deal breakup fee and accompanying wireless spectrum provided by AT&T after the deal collapsed gave T-Mobile some room to navigate and transform the company’s position — long the nation’s fourth largest national wireless carrier behind Sprint. It is now in third place, poaching customers from the other three, and has repeatedly forced other carriers to change their plans and pricing in response.

The two wireless industry giants initially ignored T-Mobile, suggesting CEO John Legere’s noisy and confrontational PR campaign had no material impact on AT&T and Verizon’s subscriber base and revenue. Ironically, Legere was named CEO one year after AT&T’s 2011 failed attempt to further consolidate the wireless industry with its acquisition of T-Mobile. A very generous deal breakup fee and accompanying wireless spectrum provided by AT&T after the deal collapsed gave T-Mobile some room to navigate and transform the company’s position — long the nation’s fourth largest national wireless carrier behind Sprint. It is now in third place, poaching customers from the other three, and has repeatedly forced other carriers to change their plans and pricing in response.

A 2016 study suggests Comcast may have more heavy users than it is willing to admit. The research firm iGR found average broadband usage that year was already at 190 GB and rising. There is no third-party verification of providers’ usage statistics or usage measurement tools, but there are public statements from Comcast officials that suggest the company faces a predictable upgrade cycle to deal with rising usage.

A 2016 study suggests Comcast may have more heavy users than it is willing to admit. The research firm iGR found average broadband usage that year was already at 190 GB and rising. There is no third-party verification of providers’ usage statistics or usage measurement tools, but there are public statements from Comcast officials that suggest the company faces a predictable upgrade cycle to deal with rising usage.