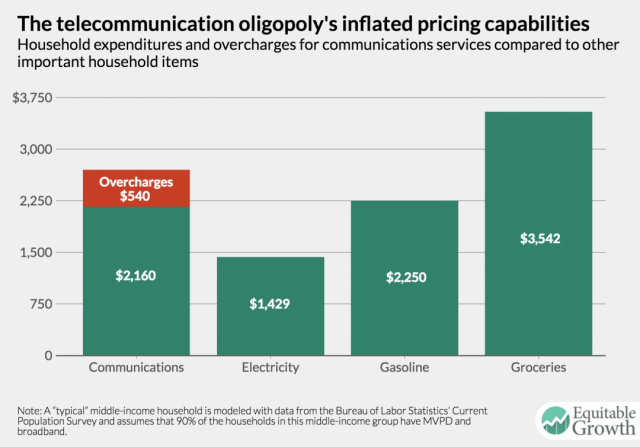

Like the railroad robber barons of more than a century ago, a handful of phone and cable companies are getting filthy rich from a carefully engineered oligopoly that costs the average American $540 a year more than it should to deliver vital telecommunications services.

Like the railroad robber barons of more than a century ago, a handful of phone and cable companies are getting filthy rich from a carefully engineered oligopoly that costs the average American $540 a year more than it should to deliver vital telecommunications services.

That is the conclusion of a new study from the Washington Center for Equitable Growth, authored by two men with decades of experience representing the interests of consumers. They recommend stopping reckless deregulation without strong and clear evidence of robust competition and ending rubber stamped merger approvals by regulators.

The trouble started with the passage of the 1996 Telecommunications Act, a bill heavily influenced by telecom industry lobbyists that, at its core, promoted deregulation without assuring adequate evidence of competition. It was that Act, signed into law by President Clinton, that authors Gene Kimmelman and Mark Cooper claim is partly responsible for today’s “highly concentrated oligopolistic markets that result […] in massive overcharges for consumer and business services.”

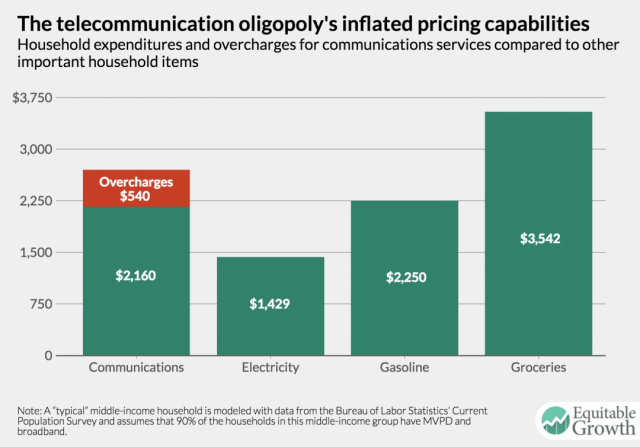

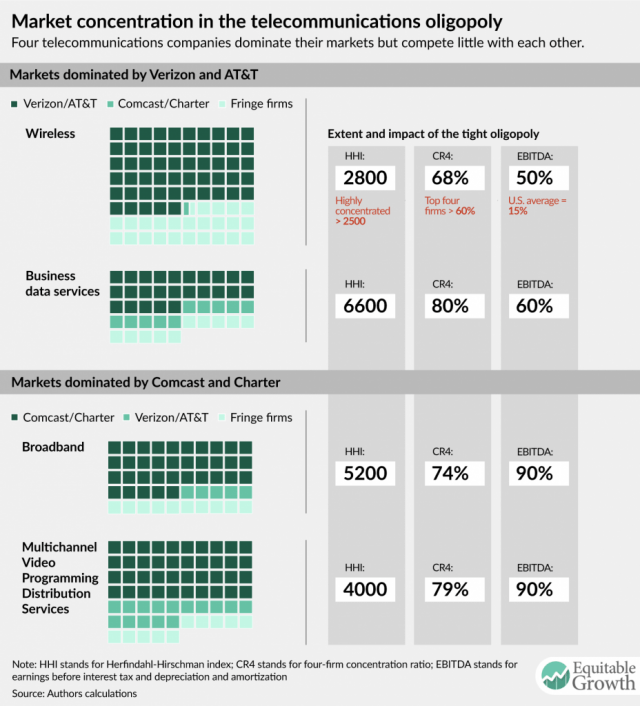

“Prices for cable, broadband, wired telecommunications, and wireless services have been inflated, on average, by about 25 percent above what competitive markets should deliver, costing the typical U.S. household more than $45 per month, or $540 per year, for these services,” the report states. “This stranglehold over these essential means of communication by a tight oligopoly on steroids—comprised of AT&T Inc., Verizon Communications Inc., Comcast Corp., and Charter Communications Inc. and built through mergers and acquisitions, not competition—costs consumers in aggregate almost $60 billion per year, or about 25 percent of the total average consumer’s monthly bill.”

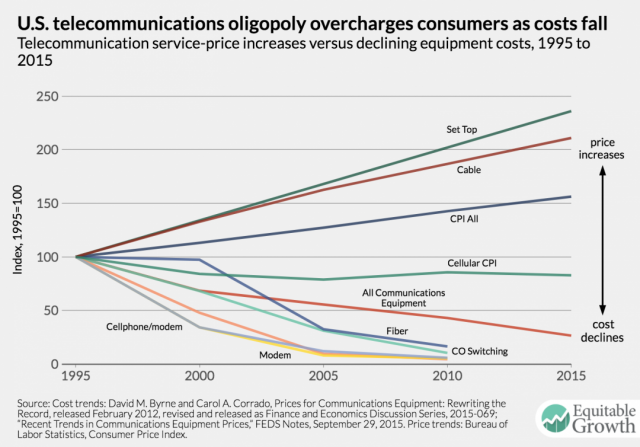

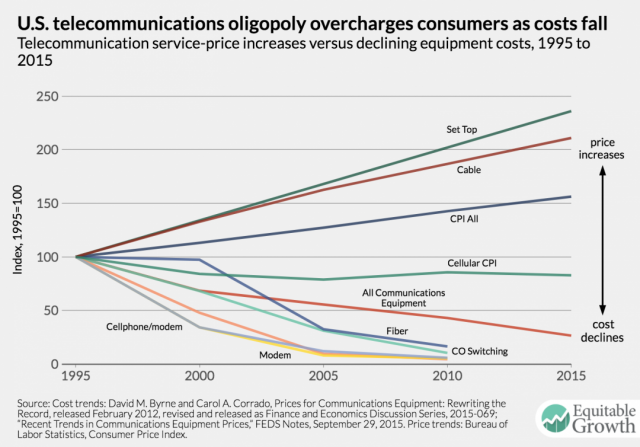

The cost of delivering service is plummeting even as your bill keeps rising.

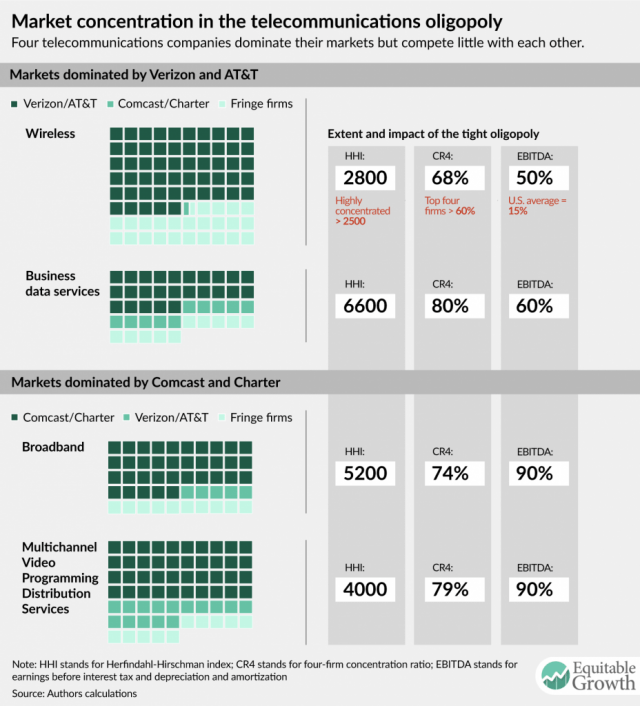

The authors also claim that these four companies earn astronomical profits — between 50 and 90% — on their services, compared with the national average of just under 15% for all industries.

The only check on these profits came from the 2011 rejection of the merger of AT&T and T-Mobile, which started a small price war in the wireless industry, saving customers an average of $5 a month, or $11 billion a year collectively.

But antitrust enforcement alone is inadequate to check the industry’s anti-competitive behavior. Competition was supposed to provide that check, but policymakers too often kowtowed to the interests of telecom industry lobbyists and prematurely removed regulatory oversight and protections that were supposed to remain in place until real competition made those regulations unnecessary.

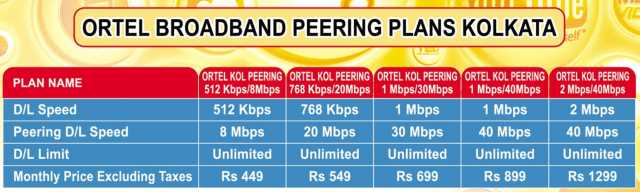

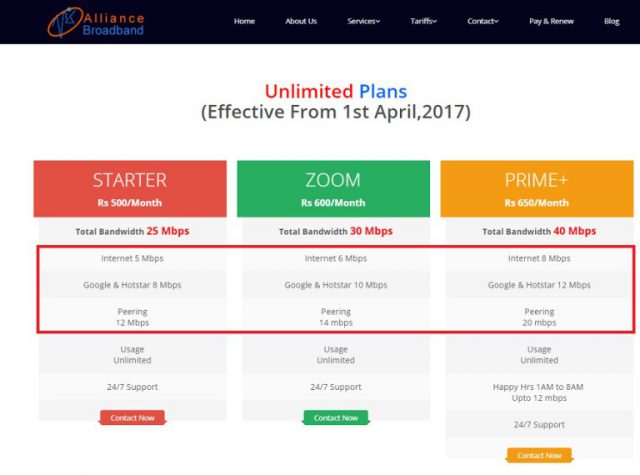

Attempts to force open closed networks to competitors were allowed in some instances — particularly with local telephone companies, but only for certain legacy services. Newer products, particularly high-speed broadband, were usually not subject to these open network policies. The companies lobbied heavily against such requirements, claiming it would deter investment.

The framers of the ’96 Act also mandated an end to exclusive franchise agreements that barred phone and cable companies from entering each others’ markets. This was intended to allow phone and cable companies to compete head to head, setting up the prospect of consumers having multiple choices for these providers.

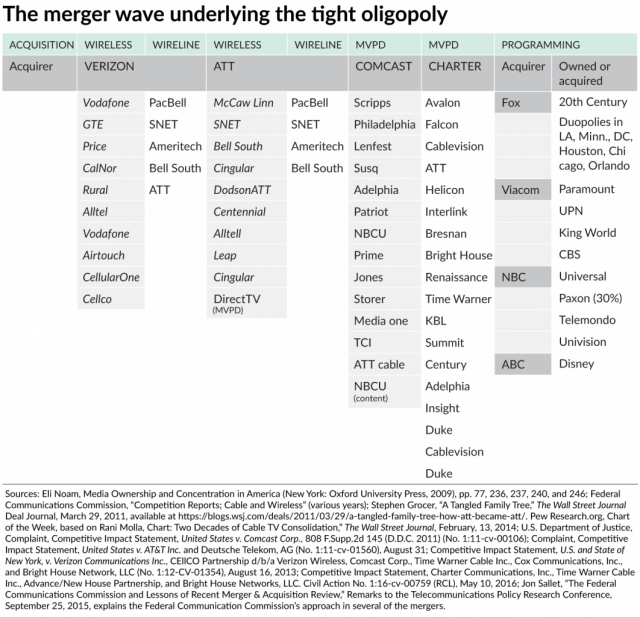

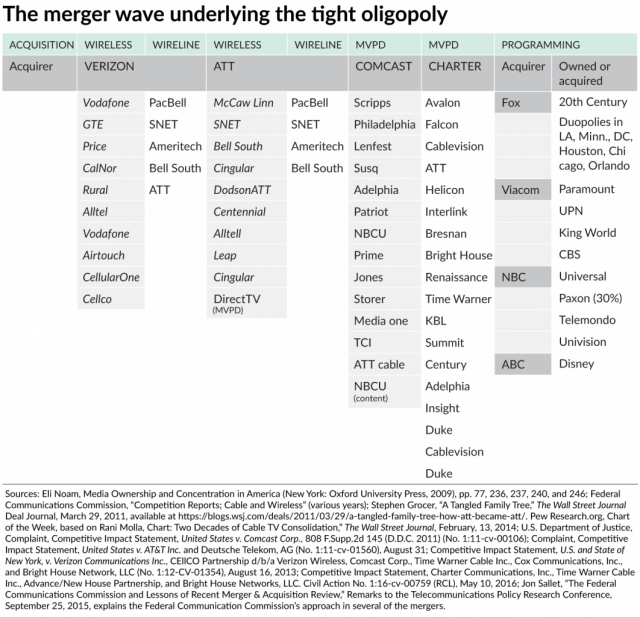

Current FCC Chairman Ajit Pai frequently cites the 1996 Communications Act as being “light touch” regulation that promulgated the broadband revolution. But in reality, the Act sparked a massive wave of corporate consolidation in broadcasting, cable, and phone companies at the behest of Wall Street.

Current FCC Chairman Ajit Pai frequently cites the 1996 Communications Act as being “light touch” regulation that promulgated the broadband revolution. But in reality, the Act sparked a massive wave of corporate consolidation in broadcasting, cable, and phone companies at the behest of Wall Street.

“[Cable companies] refused to enter new markets to compete head to head with their sister companies [and] never entered the wireless market,” the authors note. “Telephone companies never overbuilt other telephone companies and were slow to enter the video market. Each chose to extend their geographic reach by buying out their sister companies rather than competing. This means that the potentially strongest competitors—those with expertise and assets that might be used to enter new markets—are few. This reinforces the market power strategy, since the best competitors have followed a noncompete strategy.”

Wall Street sold consolidation on the theory of increased shareholder value from eliminating duplicative costs and workforces, consolidating services, and growing larger to stay competitive with other companies also growing larger through mergers and acquisitions of their own:

- The eight regional Baby Bells created after the breakup of AT&T’s national monopoly in the mid-1980s eventually merged into two huge wireline and wireless companies — AT&T and Verizon. The authors note these companies didn’t just acquire those that were part of the Ma Bell empire. They also bought out independent companies like GTE and long distance companies like MCI. Most of the few remaining independents provide service in rural areas of little interest to AT&T or Verizon.

- The cable industry is still in a consolidation wave combining large players into a handful of giants, including Comcast and Charter Communications, which also have close relationships with content providers. Altice entered the U.S. cable business principally on the prospect of consolidating cable companies under the Altice brand, not overbuilding existing companies with a competing service of its own.

Such consolidation wiped out the very companies the ’96 Act was counting on to disrupt existing markets with new competition. Comcast, Charter, and Verizon even have agreements to cross-market each others’ products or use their infrastructure for emerging “competitive” services like mobile phones and wireless broadband.

Such consolidation wiped out the very companies the ’96 Act was counting on to disrupt existing markets with new competition. Comcast, Charter, and Verizon even have agreements to cross-market each others’ products or use their infrastructure for emerging “competitive” services like mobile phones and wireless broadband.

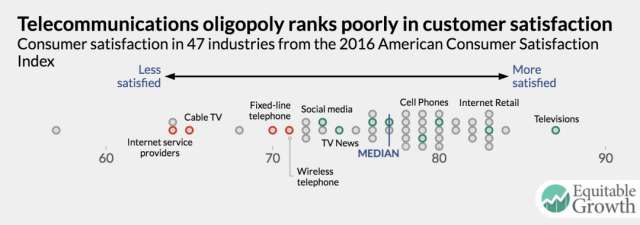

“By the standard definitions of antitrust and traditional economic analysis, a tight oligopoly has developed in the digital communications sector,” the report states. “While some markets are slightly more competitive than others, the dominant firms are deeply entrenched and engage in anti-competitive and anti-consumer practices that defend and extend their market power, while allowing them to overcharge consumers and earn excess profits.”

“The impact of this abuse of market power on consumers is clear. According to the most recent Consumer Expenditure Survey by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, the ‘typical’ middle-income household spends about $2,700 per year on a landline telephone service, two cell phone subscriptions, a broadband connection, and a subscription to a multichannel video service,” the report indicates. “Adjusting for the ‘average’ take rate of services in this middle-income group, consumers spend almost twice as much on these services as they spend on electricity. They spend more on these services than they spend on gasoline. Consumer expenditures on communications services equal about four-fifths of their total spending on groceries.”

The authors point out the Obama Administration, unlike the Bush Administration that preceded it, was the first since the 1996 Act’s passage to begin implementing policies to enhance and protect competition, and also check unfettered market power among the largest incumbent providers:

- It blocked the AT&T/T-Mobile merger, which would have removed an important competitor and affect wireless rates in just about every U.S. city. The Obama Administration’s opposition not only preserved T-Mobile as a competitor, it also made that company review its business plan and rebrand itself as a market disruptor, forcing wireless prices down substantially for the first time and collectively saving all wireless customers in the U.S. billions from rate increases AT&T and Verizon could not carry out.

- It blocked the Comcast/Time Warner Cable merger, which would have given Comcast unprecedented and unequaled control over internet access and content providers in the U.S. It would have immediately made other cable and phone companies potentially untenable because of their lack of market power and ability to achieve similar volume discounts and economy of scale, and would have blocked emerging competitors that could not create credible business plans competing with Comcast.

- It blocked informal Sprint/T-Mobile merger talks that would have combined the third and fourth largest wireless carriers. Antitrust regulators were concerned this would dramatically reduce the disruptive marketing that we still see today from both of these companies.

- It placed restrictions on Comcast’s merger with NBC Universal and Charter’s acquisition of Time Warner Cable. Comcast was required to effectively become a silent partner in Hulu, a vital emerging video competitor. Charter cannot impose data caps on its customers for up to seven years, helping to create a clear record that data caps are both unnecessary and unwarranted and have no impact on the cost of delivering internet services or the profits earned from it.

- Strong support for Net Neutrality, backed with Title II enforcement, has given the content marketplace a sense of certainty and stability, allowing online cable TV competitors to emerge and succeed, giving consumers a chance to save money by cutting the cord on bloated TV packages. If providers were given the authority to discriminate against internet traffic, it would place an unfair burden on competitors and discourage new entrants.

The authors worry the Trump Administration and a FCC led by Chairman Ajit Pai may not be willing to preserve the first gains in broadband and communications competitiveness since mergermania removed a lot of those competitors.

The authors worry the Trump Administration and a FCC led by Chairman Ajit Pai may not be willing to preserve the first gains in broadband and communications competitiveness since mergermania removed a lot of those competitors.

“The key lesson in the communications sector is that vigorous regulation and antitrust enforcement can create the conditions for market success. But balance is the key,” the reports warns. “Technological innovation and convergence are no guarantee against the abuse of market power, but the effort to control the abuse of market power should not stifle innovation. If the Trump administration jettisons the enforcement practices of the past eight years, then the telecommunications sector is likely to see a wave of new consolidation and a dampening of the price cutting and innovative wireless and broadband services that have been slowly emerging.”

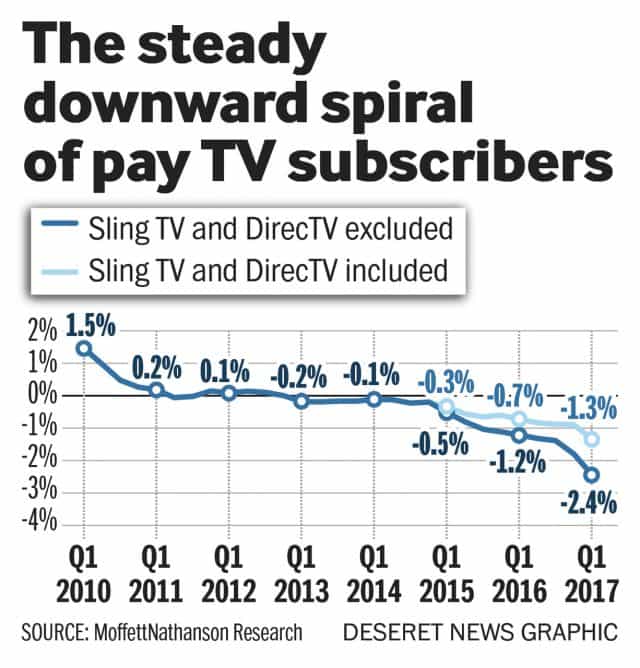

A Wall Street media analyst called today’s television model of high returns and relentless rate increases passed on to pay television customers unsustainable.

A Wall Street media analyst called today’s television model of high returns and relentless rate increases passed on to pay television customers unsustainable. Most cable networks now expect 40% annual revenue increases and a 30% return on capital, which is what causes runaway programming rate increases to be passed on year after year to consumers. Yet the quality of those networks has not significantly improved in many cases, and consumers are gradually shifting away from watching live television (and the commercials that accompany it).

Most cable networks now expect 40% annual revenue increases and a 30% return on capital, which is what causes runaway programming rate increases to be passed on year after year to consumers. Yet the quality of those networks has not significantly improved in many cases, and consumers are gradually shifting away from watching live television (and the commercials that accompany it).

Subscribe

Subscribe