“Unlimited data” must mean exactly that in the United Kingdom if you hope to survive a challenge with British regulators over advertising and tariff claims.

“Unlimited data” must mean exactly that in the United Kingdom if you hope to survive a challenge with British regulators over advertising and tariff claims.

Virgin Media thought itself clever offering “VIP” mobile customers two choices for service: £15 for a package that included 3GB of mobile data or £20 for “unlimited” data. Unlimited sounds like a great deal. For just $7.41 more, a customer could turn their stingy 3GB plan into unlimited data paradise. Or so one would think until navigating a nearly impenetrable thicket of fine print that suggested “you should expect speeds delivered up to 384kbps (3G). Actual speeds experienced may be higher or lower and will vary by device and location.”

Seven complainants discovered something interesting about their “unlimited data plan.” It sped along at an average speed of 6Mbps until they hit 3.5GB of usage during any billing cycle. After that, speeds were consistently reduced to 384kbps. They quickly learned Virgin had a secret throttling plan in place for their unlimited customers, couched in vague and misleading fine print that suggested customers should treat anything over 384kbps as a veritable gift from the mobile gods.

Why hide the fact Virgin has a “fair use policy” similar to many other wireless carriers that promise unlimited data only to throttle speeds after customers reach a certain amount of usage? Look again at Virgin’s pricing.

A customer could choose a £15 plan that included 3GB of usage or spend an extra £5 for what actually turns out to be just 500MB of regular speed data. If customers realized that, they would likely keep the £5 in their wallet. Instead, it went straight into Virgin’s bank account.

Virgin’s response is familiar to any customer who thought they bought an unlimited plan only to discover it cannot reasonably be used once an arbitrary limit is reached. The Advertising Standards Authority (ASA) summarized Virgin’s reply:

They said within all of their advertising, whenever they referred to “unlimited data” in connection with their mobile tariffs, they included an explanation within the small print that customers should expect speeds of up to 384kbit/s. They said the restriction imposed on customers was moderate in respect of the service being advertised.

They noted that the body copy of the ad did not make any reference to internet speeds, and said that Virgin Mobile customers were never prevented from accessing the internet, no matter how much data they used. They therefore maintained that access to data for any customer was entirely unlimited. They said, where a customer exceeded 3.5GB in any 30-day period, they would still be able to use the internet on their device at 3G speeds. They said that 2% of Virgin Media customers ever reached the limit in a 30-day period, which they considered was a tiny minority. They said that the customers using more than 3.5GB of data each month would be those customers who would be more aware of the advertised expected speed, and that the average consumer would therefore not have been misled.

That last sentence in particular did not amuse the regulators. In the United Kingdom, making a claim of “unlimited service” means that any limitations imposed on that service affecting speed or usability must be at most moderate and clearly disclosed. Virgin failed on both.

That last sentence in particular did not amuse the regulators. In the United Kingdom, making a claim of “unlimited service” means that any limitations imposed on that service affecting speed or usability must be at most moderate and clearly disclosed. Virgin failed on both.

Average 3G speeds in Britain are now 6.1Mbps and that speed does not vary much between providers. The ASA ruled that slashing speeds to a fraction of 6Mbps went way beyond the rules.

“Given the speeds we understood consumers were likely to achieve before the [throttle], we considered that they were likely to notice the drop in speeds once the restriction was applied, as had a number of the complainants,” wrote the ASA. “We considered that a reduction in speed from an average we understood to be approximately 6 Mbit/s to 384 kbit/s once the limit was reached, was more than a moderate reduction. Because we considered the limitation imposed on speeds to be more than moderate, we concluded that the claim ‘unlimited data’ was misleading.”

As a result, Virgin Media was told not to claim that a service was ‘unlimited’ if the limitations that affected the speed or usage of the service were more than moderate.

Subscribe

Subscribe

Last May, Comcast vice president David Cohen emphatically stated usage caps and usage-based billing were all about “fairness,” telling investors: “People who use more should pay more, and people who use less should pay less.”

Last May, Comcast vice president David Cohen emphatically stated usage caps and usage-based billing were all about “fairness,” telling investors: “People who use more should pay more, and people who use less should pay less.”

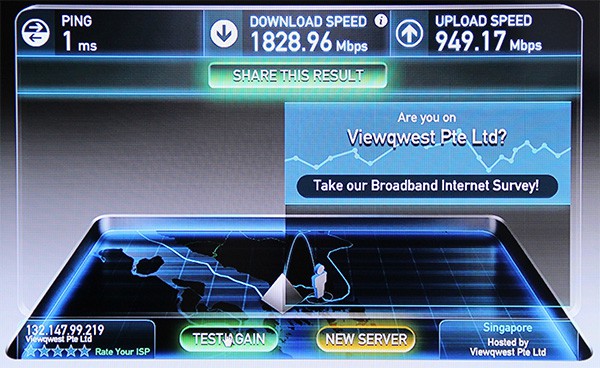

Comcast officials have repeatedly stressed its 2Gbps tier will be exempt from usage caps, which makes it the only unlimited residential broadband offering available to Comcast customers in Atlanta. Other residential customers are now subjected to a 300GB usage cap with $10/50GB overlimit fee.

Comcast officials have repeatedly stressed its 2Gbps tier will be exempt from usage caps, which makes it the only unlimited residential broadband offering available to Comcast customers in Atlanta. Other residential customers are now subjected to a 300GB usage cap with $10/50GB overlimit fee. AT&T is rolling out its gigabit fiber service in Cupertino, Calif., but if you want it you will pay $40 a month more than those who live in cities where Google Fiber offers competition.

AT&T is rolling out its gigabit fiber service in Cupertino, Calif., but if you want it you will pay $40 a month more than those who live in cities where Google Fiber offers competition. AT&T customers who do not want the company to monitor their browsing activities have to pay $29 more for privacy protection, which opts them out of AT&T’s tracking systems. Despite the high-speed and price, AT&T still insists on usage caps for its most premium broadband offering. Customers can use up to 1TB per month, after which AT&T slaps overlimit fees of $10 for each 50GB customers use over their limit. Its primary competitors, including Google, Time Warner Cable, Verizon and Charter do not have usage caps. Boyer says he knows of no customer that has exceeded the 1,000GB usage cap. But that also brings the question if no customer has exceeded the cap, why have one?

AT&T customers who do not want the company to monitor their browsing activities have to pay $29 more for privacy protection, which opts them out of AT&T’s tracking systems. Despite the high-speed and price, AT&T still insists on usage caps for its most premium broadband offering. Customers can use up to 1TB per month, after which AT&T slaps overlimit fees of $10 for each 50GB customers use over their limit. Its primary competitors, including Google, Time Warner Cable, Verizon and Charter do not have usage caps. Boyer says he knows of no customer that has exceeded the 1,000GB usage cap. But that also brings the question if no customer has exceeded the cap, why have one? Charter Communications today officially announced it will acquire control of Bright House Networks in a $10.4 billion deal the two companies are calling a “partnership.”

Charter Communications today officially announced it will acquire control of Bright House Networks in a $10.4 billion deal the two companies are calling a “partnership.” The deal is partly contingent on Time Warner Cable, which has a right to acquire Bright House for itself as part of a long-standing partnership between the two cable companies on programming and technology matters. But such an acquisition now seems remote, considering Time Warner Cable remains tied up in its year-long effort to be acquired by Comcast. An even larger Time Warner Cable would further complicate that transaction in Washington, where regulators are clearly concerned about supersizing Comcast. Since some regulators count Bright House customers as de facto Time Warner Cable customers, having Bright House acquired by Charter would seem to reduce Comcast’s influence over American broadband and cable television by cutting its combined market share from 29 to 27 million subscribers.

The deal is partly contingent on Time Warner Cable, which has a right to acquire Bright House for itself as part of a long-standing partnership between the two cable companies on programming and technology matters. But such an acquisition now seems remote, considering Time Warner Cable remains tied up in its year-long effort to be acquired by Comcast. An even larger Time Warner Cable would further complicate that transaction in Washington, where regulators are clearly concerned about supersizing Comcast. Since some regulators count Bright House customers as de facto Time Warner Cable customers, having Bright House acquired by Charter would seem to reduce Comcast’s influence over American broadband and cable television by cutting its combined market share from 29 to 27 million subscribers.