Americans have got it all wrong. Their ‘faster is better’ obsession over broadband speed threatens to harm jobs and hurts those looking for work.

Americans have got it all wrong. Their ‘faster is better’ obsession over broadband speed threatens to harm jobs and hurts those looking for work.

Those are the views of Stuart N. Brotman, a senior fellow at the Digital Policy Institute, which calls itself “a vehicle for faculty research that coalesces around the arenas of law, regulation, economics, intellectual property, and technology as these relate to public policy issues of local, state and national interests.”

Brotman argues that while broadband speeds matter, regulators should not be focused on speed as much as considering how broadband can help Americans find jobs.

The Agriculture and Commerce Depts. are tasked with administering $7.2 billion in stimulus funding for broadband by Sept. 30. As they decide where to place the bulk of those funds, which remain unawarded, government officials should show preference to grant and loan applicants that can use broadband to reach displaced workers more quickly.

There also need to be more funds made available to, and a greater focus on, public institutions, such as libraries, community centers, job training facilities, and adult education sites, where broadband spending may have the largest impact on jobs.

Greater broadband competition, which the FCC recognizes is essential to promote more infrastructure development and more varied pricing, also will be helpful. So, too, will be more efficient use of our spectrum resources, particularly those that have been controlled by colleges, schools, and other educational institutions for decades. Those airwaves can be better deployed to deliver high-speed wireless broadband services or leased to private-sector companies offering them.

Large telecommunications providers couldn’t have said it any better. They have repeatedly argued broadband speeds are besides the point.

AT&T last fall wrote the Federal Communications Commission, suggesting residential customers would do fine with broadband speeds that let them “exchange emails, participate in instant messaging, and engage in basic web-browsing.” For AT&T, speed was less important than setting “a baseline definition of the capabilities needed to support the applications and services Americans must access to participate in the Internet economy—to learn, train for jobs, and work online….”

Verizon echoed AT&T, asking the Commission to retain the current minimum definition of broadband speed at 768kbps downstream and 200kbps upstream. That allows them the chance to participate in stimulus funding projects that set the broadband speed bar low, especially in the rural areas Verizon wants to spend less on or is trying to sell-off.

“It would be disruptive and introduce confusion if the Commission were to now create a new and different definition,” Verizon said in its letter to the FCC.

Some of the smaller telecommunications companies also believe broadband speed should be de-emphasized.

Embarq, before completing a merger with CenturyTel (now CenturyLink) told the FCC 1.5Mbps broadband service has become “the most common offering.” Embarq called that “consistent with an emphasis on economic development and jobs as many important applications, such as video conferencing are arguably possible only with 1.5 Mbps service and above. Any higher speed threshold, however, would risk defining as unserved the large number of satisfied customers of 1.5 Mbps service, which seems implausible.”

Embarq underlines the real reason providers are concerned about broadband speed — they’re not delivering it. Once legislators or the Commission increases minimum broadband speed levels, many of these companies may find themselves below the threshold, guilty of “just enough speed to scrape by” in non-competitive markets. That could lead to the prospect of facing federally-funded stimulus projects from others in their service areas, now deemed “unserved” or “underserved.”

Brotman further advocates that funding be focused on those that can deliver results “quickly.”

Embarq would agree with him there as well, stating “funds through grants directly to broadband providers rather than loans or other measures as this will have the greatest and quickest impact in bringing broadband to the hardest-to-serve areas. …there is no time to wait for complete broadband maps or block grants to states for redistribution.”

Telecommunications companies would also do well by Brotman’s suggestion that federal funding for broadband projects reaching public and community service institutions should be emphasized. As communities often request companies provide those services at a deep discount or free in return for franchise agreements or other licensing provisions, that’s money AT&T, Verizon, and others need not spend out of their own pockets. Getting free airwaves swiped from educational institutions to deliver wireless broadband also benefits AT&T and Verizon, who are in that business as well.

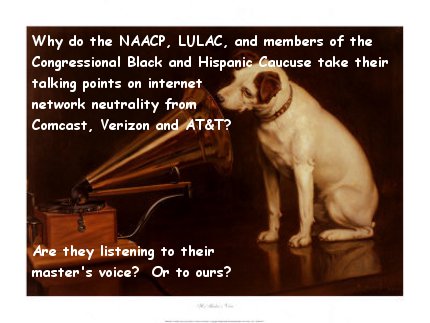

When a “policy institute,” “research group,” or other seemingly unaffiliated entity starts rehashing telecommunications industry talking points, it’s time to start digging.

Buried on page five of a PDF file describing the work of the Digital Policy Institute, one comes to a section titled, “DPI Impact and Influence.” DPI doesn’t list their financial supporters or partnerships as such. Instead, they call them “national, collaborative relationships.” Who does DPI collaborate with?

- AT&T

- Embarq

- National Telecommunications Cooperative Association (rural telco lobbyists)

- Verizon

- …among others.

Imagine my surprise.

But that’s not all. Stuart N. Brotman Communications counts (or counted) among his clients AT&T, Cox Cable, National Cable and Telecommunication Association, and the New England Cable TV Association.

Perhaps Business Week would have done a better service to readers had they also disclosed that.

Subscribe

Subscribe