Bay area residents are fuming over Comcast’s latest round of rate increases. The din grew so loud, Drew Voros, the Oakland Tribune Business Editor, noted “the annual outcry over Comcast rates is louder than any rate increase for electricity or water I have come across. A possible exception being California’s energy crisis earlier this decade.”

Voros then casually dismisses consumer outrage by telling his readers “cable TV is not a utility. It is not a vital service with transparency, public input and debate. There is no recourse for poor service through regulatory bodies or the ballot box.”

We know where this is going.

Voros doesn’t suggest that the rate increases are unjustified and unwarranted, nor does he have a bad word to say to Comcast, although he does fixate on one aspect of the regulatory framework (the wrong one) that he believes is at the core of the problem of unchecked rate increases.

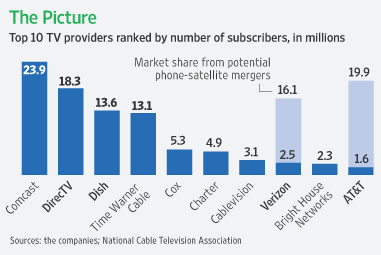

His suggestion is to watch free over the air television or try DirecTV, Dish Network or AT&T’s U-verse.

Let’s explore those alternatives.

For some, assuming they get reasonable reception, and many Bay Area residents do not, getting local over the air signals might be good enough, but won’t help with those pesky rate increases on broadband service, or for those channels like C-SPAN or cable news outlets residents access to get coverage of events local broadcasters ignore.

DirecTV and Dish Network are also fine alternatives, assuming you have permission from a landlord to install the reception equipment, and/or your view to the satellite isn’t obstructed by trees or buildings. AT&T U-verse is an even better potential choice, assuming it’s actually available in your area.

For everyone else, it’s Comzilla or go without.

Voros then goes too far into the weeds and gets lost in what suspiciously looks like “blame the government” rhetoric:

What many TV viewers do not realize is that the franchise agreements are loaded with fees and payments to the cities, funded through annual rate increases. There’s give and take between cable companies and the cities they serve. It’s a business deal with you in the middle.

But consumers are not bound by any franchise agreements, and the options for television services have grown immensely since the first cable TV line was connected in the 1970s. That is why the franchise agreements are out of date. Technology has overtaken that legal document. There’s no monopoly on television content delivery.

Ask any city official if they’d rather enjoy the incremental increase in franchise payments (which amounts to a fixed percentage, usually 3-5% of gross revenue) made possible by the annual rate hike, or the peace and quiet from constituents not upset over an industry that routinely increases rates well in excess of inflation.

Doing away with the franchise system to resolve cable rate hikes would be like using a ShamWow to deal with the after-effects of Hurricane Katrina.

Most cable companies used to include the “franchise fee” as part of the cost of the monthly service, but now routinely break that charge out onto its own line on your bill (and many never lowered the price for the original service, pocketing that as a hidden rate increase as well). A rate increase may add a few pennies to the franchise fee on a customer’s bill, but then there is the other $3-5 dollars to consider.

Franchise agreements are negotiated for wired providers. AT&T had to obtain one to provide U-verse. That’s because local communities demand that a business tearing up their streets provide something in return for the community. That usually includes: a small percentage of gross revenue, an agreement to provide free service in community centers, government offices, and public schools, and that they set aside several channels for Public, Educational, and Government access, known collectively as “PEG channels.” It’s a very small price to pay for an industry that earns billions in profits.

Those agreements typically are renegotiated every ten years, so if consumers object to the franchise fee arrangement, they can appeal to local government to reduce or eliminate it.

Voros also suggests consumers try to obtain television programming online. That is also sometimes possible, but as Stop the Cap! readers know, that also takes a broadband connection, and Comcast just raised the price for many of their customers for that as well. With the industry’s new TV Everywhere project, dropping your cable subscription, as Voros suggests, will also likely cut you off from many of your favorite cable shows online — TV Everywhere is for paid television subscribers only.

The industry has every angle covered, right down to suing to remove the exclusivity ban on cable networks and programming. Should the DC Court of Appeals agree, Voros’ contention that there’s no monopoly on television content delivery will also be thrown into doubt.

The solution is not to blame “outdated” franchise agreements. The cable package business model is the larger problem. Customers are expected to pay for ever-growing and more costly basic and digital cable packages filled with channels they don’t want. Of course competition should be encouraged, but allowing consumers to choose and pay for only the channels they wish is a far better solution to runaway cable pricing.

Subscribe

Subscribe