Samuel Greenholtz, a retired manager from Verizon, offered this absolutely impenetrable thinking on why broadband providers needed to impose caps on customers and were forced to charge way too much for them:

While a tiered pricing structure may have been inevitable in the long run, if the corporate bashing horde stayed out of the way, the vast majority of users would have avoided paying more for additional capacity. Time Warner Cable does give the politicians what they are looking for – more bandwidth availability for all of its subscribers. Still, the lowest speed package is not going to be enough for most of the consumers – and so they will have to take the higher tier offerings — along with the new overage charges. Had the MSOs been allowed to just cap excessive users, most of the subs would have continued to receive a reasonable amount of bandwidth at the same flat price.

Ironically, all of the illogic obsession with net neutrality will result in even more of a usage-based pricing scheme. There will now be several layers of capping. The anti-ISP crowd has actually created a more beneficial pricing system for these companies. And there is certainly nothing unfair about this development. But the clamoring for so-called equality resulted in an acceleration of the removal of the all-you-can-eat advantage for consumers.

What in the world is this man talking about, and why is he part of some so-called “expert network,” Gerson Lehrman Group?

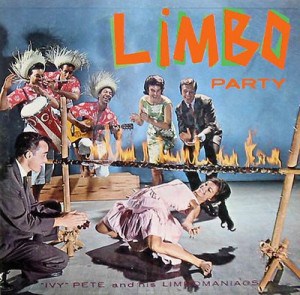

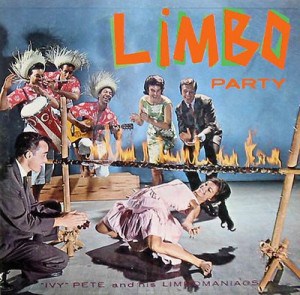

Broadband Providers: How Low Can They Go?

The history of usage capping actually goes back into the earliest days of Internet service providers, providing both dial-up and broadband service in areas where network capacity simply didn’t allow customers to utilize unlimited bandwidth. Some Time Warner customers in the midwest and central part of the country lived under “limits” for years, mostly due to lack of any viable competition. The imposition of caps on customers has always been driven by the capacity argument, never by a more honest claim that lack of competition discourages significant upgrades, and allows a provider to limit usage to ensure a higher rate of return. Where competition exists offering similar types of service, caps and limits are much rarer, speeds are higher, and pricing is lower. A provider that doesn’t regularly invest in upgrades to his network in a competitive marketplace will soon no longer be a part of that marketplace.

Today, a handful of major broadband providers are now colluding in a version of telecommunications limbo, with several watching each of the others “experiment,” to see how low a cap they can set before subscribers and public officials rebel. Multichannel News columnist Todd Spangler literally wrote that “Time Warner is taking one for the team.”

The “corporate bashing horde” argument, which Greenholtz casually tosses out without any examples or proof, doesn’t hold water. No group I am aware of has ever bashed the widespread deployment of broadband service from multiple providers. Oh wait, there is one. Those providers themselves when they attempt to squelch community cooperative broadband services or municipally-run wi-fi networks, run for the benefit of residents.

Greenholtz completely ignores the fact broadband service is almost entirely unregulated, and providers have always been free to set terms and prices. Someone draw me a map where corporate critics have developed the leverage to force operators to impose usage caps and tiered pricing.

The net neutrality issue that comes into his argument stems from the Comcast controversy a few years ago, when the nation’s largest cable operator attempted to manage traffic on its network by “throttling,” or limiting the speed of customers using certain bandwidth intensive applications. Comcast claimed they were primarily targeting peer-to-peer software, which allows users to exchange files with one another, during peak usage of their network.

But this came about at the same time several large corporate broadband providers were advocating for a new distribution system for the Internet, one that would potentially no longer provide an equal level of priority for data traveling across the Internet. Opponents feared that broadband providers could discriminate or even throttle traffic that didn’t pay their asking price. And then Comcast provided the net neutrality opponents with a real-world example of bandwidth throttling in action.

Comcast abandoned, at least for now, the bandwidth management approach that included throttling, and instead imposed a simple 250GB “limit” on residential accounts. Those exceeding that amount of usage risked having service suspended.

Mr. Greenholtz fails to connect this event with any cogent argument or evidence that suggests multiple capped tiers were borne as a result of this controversy. Indeed, until Time Warner “took one for the team,” other domestic broadband providers simply upgraded their networks to handle capacity issues and imposed no caps, or have simply asked residential users to limit their usage, mostly between 150-250GB per month. Customers seeking more than that can purchase another account, move to a business plan, or switch to another provider, where available. Curiously, the imposition and testing of lower limits has often been in areas where competitors either do not exist or cannot offer an equivalent level of service at the same price across an entire community.

But Greenholtz does say one thing that has been obvious to all of us: the Internet service provider is using this as an excuse to create a “more beneficial pricing system.” Of course, it’s only beneficial to them, not to consumers. The latter routinely object in overwhelming majorities to the concept of usage caps and the elimination of the existing flat rate pricing which has always been profitable for the broadband industry. Any other connection, particularly with the absence of any evidence, is tenuous at best.

Subscribe

Subscribe

Mr. Kim then suggests he doesn’t necessarily like his electricity or water rates, but he conserves because there is a penalty for unrestrained use. Actually, there isn’t really a penalty at all. Gas, electric, and water service are sold on a true metered basis. There are no “bucket plans” for these services. They are also utilities, and their rates are either regulated outright, or carefully monitored in the limited competition models some states have for these services.

Your water company bears the minimal cost of pumping a gallon of water from a body of water or aquifer. It then resells that water at a per gallon rate marked up to cover all of the overhead and expenses it has, sets a little more aside just in case of a non-rainy day, and delivers it to you at a rational, non-gouging price. If you don’t want to pay, you leave the faucet off. On the Internet, the faucet drips… all the time. The only way you are assured of not paying is to unplug your modem, never check your e-mail, and avoid websites with ads, because those are now now on your dime, especially when Time Warner marks up its wholesale cost by 1000% or more for that data. It’s like getting a glass of water but handing half of it to the stranger walking by your house, who also wants you to pay him a dollar on top of that.

Time Warner is also, like many cable providers, hip deep in a conflict of interest on broadband consumption. Cable has a vested interest in forcing you to “conserve” your connection, particularly by not using those services which directly compete with its business models. Streaming video online offers the customer the possibility of foregoing a cable TV package altogether. A Voice Over IP telephone provider on the Internet makes Time Warner’s Digital Phone product redundant. A Netflix set-top box that streams movies and other video programming in competition with premium/pay per view channels represent just one more service that panics many in the upper floors at Time Warner Cable’s headquarters.

Ironically, it was the very same cable companies that are whining about Exafloods and a crisis of costs who have contributed to the demise of “long distance.” Time Warner, among others, are now pitching cheap unlimited calling plans to customers who will never pay for another long distance call. In the wireless industry, price skirmishes have already broken out with carriers marketing true unlimited calling plans or calling circles which, for most people, mean no more airtime minute watching.

When I renew my Verizon Wireless contract this December, I will be handed a new phone and the option of a better plan with more minutes at or below the price I am paying now. By that time, there is every likelihood Time Warner will be asking me to pay three times more ($150 a month) for precisely the same level of service I am receiving now for around $50 a month. One of these companies is responding to the reality that bandwidth costs are declining, and are reducing rates and offering more. The other is taking advantage of a very limited competitive market and wants to triple charges claiming they are on the edge of broadband bankruptcy — only they’re not when you read their financial reports. Guess which is which.

I am also glad you are asking real people these questions, because companies like Time Warner certainly aren’t. Any reader here can recite poll after poll. The overwhelming majority of broadband customers, even those who are not defined “at the moment” as “abusers” of the network are content and satisfied paying one monthly fee for their service. They don’t want your plan, the industry’s plan, buckets, limits, caps, overlimits, or whatever else the marketing people decide to call the equivalent of Internet rationing at top dollar pricing.

We are consumers. We are customers. We are not industry insiders and we don’t write for industry trade publications. We don’t get a paycheck from this industry. Indeed, this industry raises our bill year after year, delivers inconsistent messages about why we are now being asked to pay for “buckets of broadband,” yet still denies us the ability to choose the channels we want for our own video package, paying just for what we want.

We also are empowered and educated enough to use this incredible tool called the Internet to research the assertions some make and simply expect others to accept at face value. We now read financial reports and statements. We verify. We also discover the language of the lobbyist, the marketers, the astroturfers, and the executive elements that are now attempting to sell consumers on their scheme to pay considerably more for the exact same thing, or less. Then we compare that with the glowing results given to shareholders, and we see the chasm between the two messages. We realize what we are being sold: a soon-to-be-even-more-inflated bill of goods.

Frankly, you don’t have to be a genius to recognize that looking at a gas gauge, worrying about overlimit fees, and being stuck paying $100 more a month for broadband is not going to make anyone outside of this industry happy.

The first time a consumer gets a bill from a company with a plan like Time Warner’s, they are going to kick the bucket.

Anyone who doesn’t recognize and admit the real potential of market abusive pricing and policies in a limited competitive marketplace isn’t being completely honest, especially when the players do not offer roughly equivalent levels of service. If the future of broadband in this country is to be unregulated virtual duopolies, then perhaps consumers need to insist on common carrier status for those networks, allowing equal access to a variety of competing providers, with oversight to guarantee fair wholesale pricing and access.