You’ve heard all the excuses:

- Internet traffic has grown and unlimited pricing threatens to make broadband unprofitable;

- We need these pricing schemes to help pay for improved infrastructure to handle traffic;

- If we don’t adopt this pricing now, a great data tsunami — an exaflood — will wash broadband down the sink;

- It’s not fair to make light users pay for heavier users.

Despite the fact provider financial reports show a trend towards reduced spending on infrastructure, data transport costs continue to drop, and debunking of exaflood horror tales, providers persist in demands for this so-called “fairer pricing” for broadband service.

But what is fair?

As Canada contends with an Internet Overcharging scheme that limits consumption to an average of 40-60GB per month, with $1-5 per gigabyte in overlimit fees, does this represent fair pricing?

The Toronto Globe & Mail decided to investigate, and the results will come as no surprise to readers here.

Fact: Usage is growing exponentially, especially among users streaming online video. Canadians, just like Americans, are swarming towards multimedia-rich content from YouTube to Netflix. Usage growth of 50 percent per year is not out of line. But as the newspaper discovered, extraordinary growth alone does not deliver the whole story. The capacity to handle that Internet traffic has not only kept up with growth, it has exceeded it, at levels of unprecedented efficiency.

The Globe & Mail notes:

[…] Processing power, hard disk densities and transmission rates grew at rates closer to 60 per cent per year over the same period. In addition, the servers and routers and other electrical equipment that are the backbone of the Internet are much more energy efficient than they were ten years ago, which has dramatically reduced the cost of operations.

In simple terms, the bandwidth explosion is real, but it’s been more than offset by more powerful and more energy-efficient machines. So, we can reject the notion that increased usage is the a significant rationale for huge Internet price increases and usage-based billing.

Among virtually every provider, the percentage of average revenue spent on broadband network expansion per customer has dropped. Even Verizon, which suspended expansion of its fiber to the home network, has not faced an avalanche of new costs to deliver large amounts of data to FiOS customers.

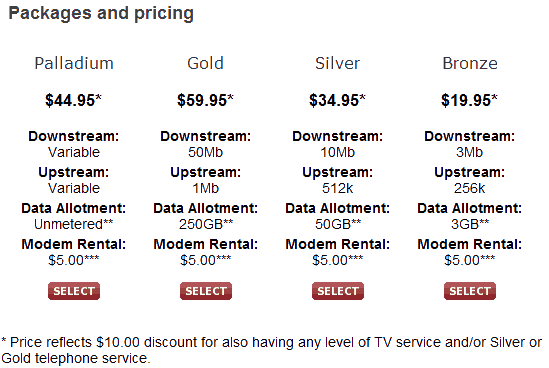

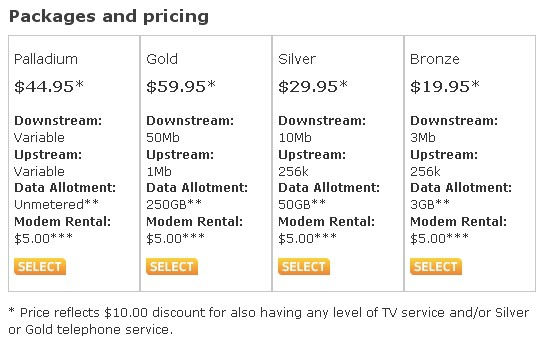

But what about the “fairness” proposition. Should light users pay less than heavy users? Historically, even in countries where usage-based pricing is the norm, usage-limited customers still pay comparatively high prices for broadband service, particularly when measured on cost per megabit per second against the usual lower caps cheaper plans provide. So-called “light usage” plans also have natural usage caps built-in — they come with far slower speeds that, at their worst, discourage use of high bandwidth services.

The Globe & Mail concluded: “Rather than ensuring consumers receive fair Internet pricing, the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission seems content to line the pockets of cable and telecommunications companies by forcing Canadian consumers to pay Internet data rates that have no basis in reality.”

Here’s why:

Wholesale Data Costs

The “fairness” argument falls apart when the truth is revealed about the wholesale costs large providers pay for their Internet connections. Assuming the providers’ arguments that pay-per-use pricing is fair, the prices they ask Canadians to pay for that use certainly are not.

The Globe & Mail again:

Approximately four years ago, the cost for a certain large Telco to transmit one gigabyte of data was around 12 cents. That’s after all of its operational and fixed costs were accounted for. Thanks to improved technology and more powerful machines, that number dropped to around 6 cents two years ago and is about 3 cents per gigabyte today.

Are these valid numbers? After the recent CRTC decision regarding UBB, it was announced that effective March 1st, Bell will be charging Third Party Internet Access (TPIA) providers $4.25 for a 40 GB block of additional data transfer.

The fact that Bell is able to sell 40 GB of data to wholesalers for $4.25 and still make a profit demonstrates that the true cost of data transfer is well below the 10.5 cents per gigabyte they are charging wholesalers. One TPIA provider agreed the 3 cents per gigabyte figure is probably close to the true cost.

So why are Internet service providers charging consumers $1 or more per gigabyte of data used beyond their respective data caps? That’s a good question.

The “good answer” is: profits.

With providers charging overlimit fees from $1 per gigabyte on Bell’s most generous plans to $5 per gigabyte for Rogers’ Ultra-Lite plan, this represents overcharging of at least 10-50 times what it actually costs the providers to deliver that data.

Broadband costs in the United States are dramatically lower than in Canada, in part because of a larger marketplace and because of greater capacity and more competition, yet proposals from some American providers sought similar limits and overage pricing.

But considering the true cost of the service, charging closer to 10 cents per gigabyte — not $1 or more — would represent a fair price. So long as regulators like the CRTC cater to providers, consumers will pay considerably more.

[flv width=”480″ height=”380″]http://www.phillipdampier.com/video/CTV Usage Based Billing 2-1-11.flv[/flv]

CTV News explores Usage-Based Billing, and why it will makes an expensive broadband experience even more costly in the days ahead. (6 minutes)

Subscribe

Subscribe