The pro-Internet Overcharging forces’ meme of “pay for what you use” sounds good in theory, but no broadband provider in the country would dare switch to a true consumption-based billing system for broadband, because it would destroy predictable profits for a service large cable and phone companies hope you cannot live without.

Twenty years ago, the cable industry could raise rates on television packages with almost no fear consumers would cancel service. When I produced a weekly radio show about the cable and satellite television industry, cable companies candidly told me they expected vocal backlashes from customers every time a rate increase notice was mailed out, but only a handful would actually follow through on threats to cut the cord. Now that competition for your video dollar is at an all-time-high, providers are shocked (and some remain in denial) that customers are actually following through on their threats to cut the cord. Goodbye Comcast, Hello Netflix!

Some Wall Street analysts have begun warning their investor clients that the days of guaranteed revenue growth from video subscribers are over, risking profits as customers start to depart when the bill gets too high. Cable companies have always increased rates faster than the rate of inflation, and investors have grown to expect those reliable profits, so the pressure to make up the difference elsewhere has never been higher.

With broadband, cable and phone companies may have found a new way to bring back the Money Party, and ride the wave of broadband usage to the stratosphere, earning money at rates never thought possible from cable-TV. The ticket to OPEC-like rivers of black gold? Usage-based billing.

Since the early days of broadband, most Americans have enjoyed flat rate access through a cable or phone company at prices that remained remarkably stable for a decade — usually around $40 a month for standard speed service.

In the last five years, as cord-cutting has grown beyond a phenomena limited to Luddites and satellite dish owners, the cable industry has responded. As they learned customers’ love of broadband has now made the service indispensable in most American homes, providers have been jacking up the price.

Time Warner Cable, for example, has increased prices for broadband annually for the last three years, especially for customers who do not subscribe to any other services.

Time Warner Cable, for example, has increased prices for broadband annually for the last three years, especially for customers who do not subscribe to any other services.

Customers dissatisfaction with rate hikes has not led to broadband cord cutting, and in fact might prove useful on quarterly financial reports -and- for advocating changes in the way broadband service is priced:

- Enhance revenue and profits, replacing lost ground from departing video customers and the slowing growth of new customers signing up for video and phone services (and keeping average revenue per user ((ARPU)) on the increase);

- Using higher prices to provoke an argument about changing the way broadband service is sold.

Pouring over quarterly financial reports from most major providers shows remarkable consistency:

- The costs to provide broadband service are declining, even with broadband usage growth;

- Revenue and profits enjoy a healthy growth curve, especially as increased prices on existing customers make up for fewer new customer additions;

- Earnings from broadband are now so important, a cable company like Time Warner Cable now refers to itself as a broadband company. It is not alone.

Still, it is not enough. As usage continues to grow in the current monopoly/duopoly market, providers are drooling with anticipation over the possibility of scrapping the concept of “flat rate” broadband, which limits the endless ARPU growth Wall Street demands. If a company charges a fixed rate for a service, it cannot grow revenue from that service unless it increases the price, sells more expensive tiers of service, or innovates new products and services to sell.

Providers have enjoyed moderate success selling customers more expensive, faster service, also on a flat rate basis. But that still leaves money on the table, according to Wall Street-based “usage billing” advocates like Craig Moffett, who see major ARPU growth charging customers more and more money for service as their usage grows.

Moffett has a few accidental allies in the blogger world who seem to share his belief in “usage-based” billing. Lou Mazzucchelli, reading the recent New York Times piece on Time Warner’s gradual move towards usage pricing, frames his support for consumption billing around the issue of affordability. In his view, usage pricing is better for consumers and the industry:

It costs real money to upgrade networks to keep pace with this demand, and those costs are ultimately borne by the subscriber. So in the US, we have carriers trying to raise their rates to offset increases in capital and operating expenses to the point where consumers are beginning to push back, and the shoving has come to the attention of the Federal Communications Commission, which has raised the possibility of treating Internet network providers as common communications carriers subject to regulation.

I believe that flat-rate pricing is a major source of problems for network carriers and consumers. In the carrier world, the economics are known but ignored because marketers believe that flat rates are the only plans consumers will accept. But in the consumer world, flat rates are rising to incomprehensible levels for indecipherable reasons, with little recourse except disconnection. Consumer dissatisfaction is rising, in part because consumers feel they have no control over the price they have to pay. This is driven by their sense of pricing inequity that is hard to visualize but comes from implicit subsidies in the current environment. The irony is that pay-per-use pricing solves the problem for carriers and consumers.

Mazzucchelli reposted his blog piece originally written in 2010 for the benefit of Times readers. Two years ago, he measured his usage at 11GB a month. His provider Verizon Communications was charging him $64.99 a month for 25Mbps service, which identifies him as a FiOS fiber to the home customer. Mazzucchelli argues the effective price he was paying for Internet access was $5.85 for each of the 11GB he consumed, which seemed steep at the time. (Not anymore, if you look at wireless company penalty rates which range from $10-15/GB or more.)

Mazzucchelli theorized that if he paid on a per-packet basis, instead of flat rate service based on Internet speed, he could pay something like $0.0000025 per packet, which would result in a bill of $31.91 for his 11GB instead of $65. For him, that’s money saved with usage billing.

On its face, it might seem to make sense, especially for light users who could pay less under a true usage-based pricing scenario like the one he proposes.

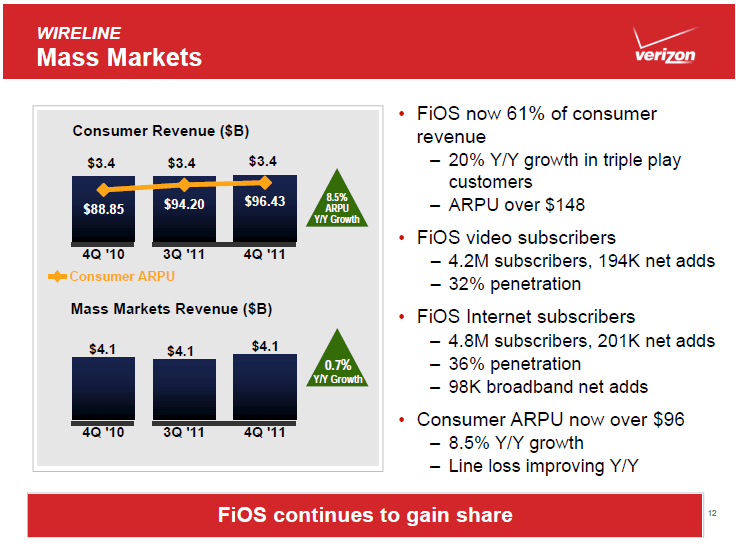

Verizon Communications is earning more average revenue per customer than ever with its fiber to the home network. That’s about the only bright spot Wall Street recognizes from Verizon’s fiber network, which some analysts deride as “too expensive.”

Unfortunately for Mazzucchelli, and others who claim usage-based pricing will prove a money-saver, the broadband industry has some bad news for you. Usage pricing simply cannot be allowed to save you, and other current customers money. Why? Because Wall Street will never tolerate pricing that threatens the all-important ARPU. In the monopoly/duopoly home broadband marketplace most Americans endure, it would be the equivalent of unilaterally disarming in the war for revenue and profits.

That is why broadband providers will never adopt a true usage-based billing system for customers. It would cannibalize earnings for a service that already enjoys massive markups above true cost. In 2009, Comcast was spending under $10 a month to sell broadband service priced above $40.

Instead, providers design “usage-based” billing around rates comparable to today’s flat rate pricing, only they slap arbitrary maximum usage allowances on each tier of service, above which consumers pay an overlimit fee penalty. That would leave Mazzucchelli choosing a lower speed, lower usage allowance plan to maximize his savings, if his use of the Internet didn’t grow much. On a typical light use plan suitable for his usage, he would subscribe to 1-3Mbps service with a 10GB allowance, and pay the overlimit fee for one extra gigabyte if he wanted to maximize his broadband dollar.

But his usage experience would be dramatically different, both because he would be encouraged to use less, fearing he might exceed his usage allowance, and he would be “enjoying” the Internet at vastly slower speeds. If Mazzucchelli went with higher speed service, he would still pay prices comparable for flat rate service, and receive a usage allowance he personally would find unnecessarily large. The result for him would be little to no savings and a usage allowance he did not need.

Mazzucchelli’s usage pattern is probably different today than it was in 2010. Is he still using 11GB a month? If he uses double the amount he did two years ago, under his own pricing formula, the savings he sought would now be virtually wiped out, with a broadband bill for 22GB of consumption running $63.82. By the following year, usage-based pricing would cost even more than Verizon’s unlimited pricing, as average use of the Internet continues to grow.

That helps the broadband industry plenty but does nothing for consumers. Mazzucchelli might be surprised to learn that the “real money to upgrade networks to keep pace with this demand,” is actually more than covered under today’s profit margins for flat-rate broadband. In fact, if he examines financial reports over the last five years and the statements company executives make to shareholders, virtually all of them speak in terms of reducing capital investments and the declining costs to deliver broadband, even as usage grows.

Verizon’s fiber network, while expensive to construct, is already earning the company enormous boosts in ARPU over traditional copper wire phone service. While Wall Street howled about short term capital costs to construct the network, then-CEO Ivan Seidenberg said fiber optics was the vehicle that will drive Verizon earnings for decades selling new products and services that its old network could never deliver.

Still, is Mazzucchelli paying too much for his broadband at both 2010 and 2012 prices? Yes he is. But that is not a function of the cost to deliver broadband service. It is the result of a barely competitive marketplace that has an absence of price-moderating competitors. Usage-based pricing in today’s broadband market assures lower costs for providers by retarding usage. It also brings even higher profits from bigger broadband bills as Internet usage grows, with no real relationship to the actual costs to provide the service. It also protects companies from video package cord-cutting, as customers will find online viewing prohibitively expensive.

One need only look at pricing abroad to see how much Americans are gouged for Internet service. Unlimited high speed Internet is available in a growing number of countries for $20-40 a month.

Usage-based billing is a dead end that might deliver temporary savings now, but considerably higher broadband bills soon after. It is not too late to turn the car around and join us in the fight to keep unlimited broadband, enhance competition, and win the lower prices users like Mazzucchelli crave.

Subscribe

Subscribe