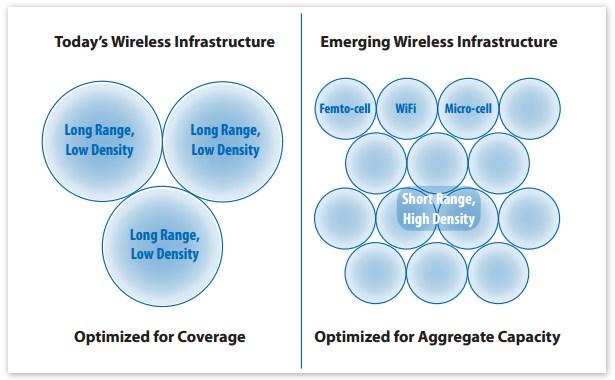

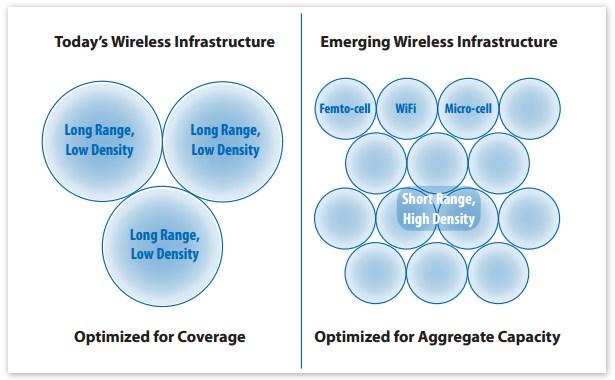

The wireless industry is in transition. Increasing capacity also means decreasing the number of customers trying to share a traditional cell tower. The future will bring a combination of shorter-range cellular and Wi-Fi antennas that can sustain traffic loads much easier than overburdened traditional cell towers.

The President’s Council of Advisors on Policy and Technology’s recommendation that the growing demand for wireless spectrum be met by sharing frequencies with the federal government is getting a cold reception from the wireless industry.

AT&T, other wireless operators, and their lobbying trade association have been embarked on a fierce campaign in Washington to free up additional spectrum they can use to meet growing demands for wireless data. Unfortunately, clearing spectrum that can be re-purposed for wireless phone companies requires complicated, and often expensive frequency reassignments as existing users relocate elsewhere. With the federal government holding a large swath of spectrum for the use of a range of public safety, research, and military applications, the best source for new frequencies comes from Washington.

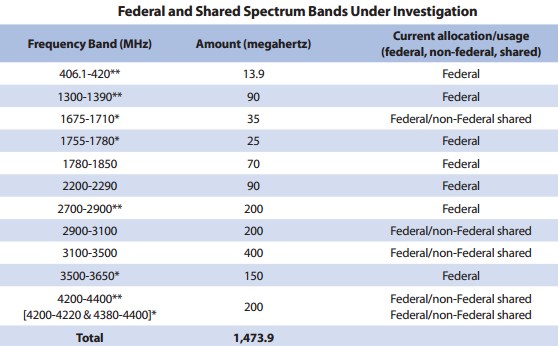

PCAST’s final 200-page report urges the Commerce Department prioritize locating 1000MHz of frequencies that could be re-purposed for private wireless communications. But the council also recommended that frequencies could be more quickly made available by asking wireless telecom companies to share them with existing users.

Today’s “exclusive use” licenses all too often are being underutilized and, in fact, are sometimes used as a valuable investment tool to buy, trade, or sell. Issuing exclusive licenses guarantees that no other players can use those frequencies. That is a valuable tool for wireless companies protecting their market share from potential competitors.

PCAST declared the concept of a “spectrum shortage” to be largely a myth:

Although there is a general perception of spectrum scarcity, most spectrum capacity is not used. An assigned primary user may occupy a band, preventing any other user from gaining access, yet consume only a fraction of the potential spectrum capacity. Unique among natural resources owned by the public, spectrum capacity is infinitely renewable from second to second—that is, any spectrum vacated by one user is immediately available for any other user.

Measurements of actual spectrum use show that less than 20 percent of the capacity of the prime spectrum bands (below 3.7 GHz) is in use even in the most congested urban areas.

This spectrum inefficiency is not just a problem for the wireless industry, it also afflicts government use as well. But it is a problem that can be solved by modernizing spectrum allocation policy in the United States.

“Exclusive frequency assignments should not be interpreted as a reason to preclude other productive uses of spectrum capacity in areas or at times where the primary use is dormant or where underutilized capacity can be shared,” the report concludes.

If implemented, the wireless industry could begin accessing hundreds of megahertz of new spectrum, with the understanding there may be other users sharing certain frequencies in different areas at different times. For example, AT&T could use spectrum assigned to forest rangers in federal parks for wireless data in Manhattan or other urban areas, where neither user will create interference for the other. Verizon could use spectrum allocated for naval communications at seaside ports in land-locked Nebraska, Utah, Kansas, or West Virginia.

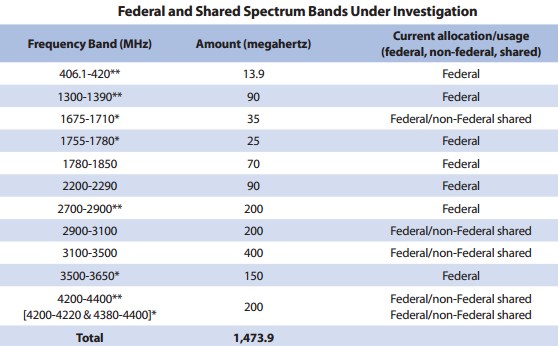

The proposal identifies these frequency bands as ideal for shared use between private and government users.

As technology progresses, shared spectrum users will easily afford equipment that dynamically locates open frequencies for communications with little or no interference even if two users are located right next door to each other.

The benefits to taxpayers, governmental users, and private industry are notable:

- The cost to relocate existing government users to other bands is prohibitively time-consuming, complicated, and expensive. Taxpayers often foot the bill for the frequency changes;

- Government use of spectrum is not particularly efficient either. Identifying under-utilized spectrum for shared-use can bring pressure to government users to consolidate operations and increase operating efficiency;

- Private industry gets much faster access to new spectrum, which suddenly becomes plentiful and potentially affordable for new entrants in the wireless marketplace.

Despite the benefits, the wireless industry had a frosty reception to the new report:

Joan Marsh, AT&T Vice President of Federal Regulatory:

Joan Marsh, AT&T Vice President of Federal Regulatory:

“While we are still reviewing the PCAST report, we are encouraged by the sustained interest in exploring ways to free up underutilized government spectrum for mobile Internet use. However, we are concerned with the report’s primary conclusion that ‘the norm for spectrum use should be sharing, not exclusivity.’ The report fails to recognize the benefits of exclusive use licenses, which are well known. Those licenses enabled the creation of the mobile Internet and all of the ensuing innovation, investment and job creation that followed.

“While we should be considering all options to meet the country’s spectrum goals, including the sharing of federal spectrum with government users, it is imperative that we clear and reallocate government spectrum where practical. We fully support the NTIA effort of determining which government bands can be cleared for commercial use, and we look forward to continuing to work with NTIA and other stakeholders to make more spectrum available for American consumers and businesses.”

CTIA – The Wireless Association:

The CTIA is the wireless industry’s lobbying group

“We thank the Administration and PCAST for focusing on the need to make more efficient use of spectrum currently assigned to federal government users. As the PCAST report notes, it is sensible to investigate creative approaches for making federal government spectrum commercially available, including the development of certain sharing capabilities. At the same time, and as Congress recognized in the recently-passed spectrum legislation, the gold standard for deployment of ubiquitous mobile broadband networks remains cleared spectrum.

“Cleared spectrum and an exclusive-use approach has enabled the U.S. wireless industry to invest hundreds of billions of dollars, deploying world-leading mobile broadband networks and resulting in tremendous economic benefits for U.S. consumers and businesses. Not surprisingly, that is the very same approach that has been used by the countries that we compete with in the global marketplace, who have brought hundreds of megahertz of cleared spectrum to market in recent years.

“Policymakers on a bipartisan basis have grasped the importance of making more spectrum available to meet the growing demand for mobile Internet services, and this report highlights a range of forward-looking options, some of which are not yet commercially available, that may be considered to meet this important national goal. We look forward to continuing to work with the Administration, the FCC, NTIA, Congress and other interested parties to increase access to federal government spectrum and to continue to assist our nation in its economic recovery.”

Wireless carriers will continue to lobby Washington lawmakers to leave the current “exclusive use” spectrum policies in place, even if it delays opening up “badly-needed” spectrum for years.

In short, the major players in the wireless industry are hostile to the idea of losing exclusive-use spectrum. That comes as little surprise because shared spectrum cannot be controlled by the wireless industry. Spectrum squatting, where large phone companies or investment groups hang on to unused spectrum either to keep competitors out or as an investment tool until it eventually can be resold at a major profit, is a significant problem in the industry. Wall Street analysts routinely assign value to the spectrum holdings of wireless carriers, whether they are used or not. Since most spectrum is now sold to the industry at “highest bidder wins” auctions, only the largest players are frequently serious contenders. Auctioning off shared spectrum, if practical, will bring lower bids — but could potentially bring new bidders like start-up ventures that have some new ideas on how to use wireless frequencies to compete.

Therefore, it has been in the wireless industry’s best interests to keep the idea of sharing frequencies with other players out of the minds of Washington regulators and legislators. Their technical objections and claims that shared spectrum would somehow destroy innovation and investment ring hollow, and are weak deflections from the more obvious agenda: to maintain their status quo control of wireless frequencies, well-utilized or not.

AT&T and other wireless players will no doubt lobby their case to Washington politicians, many who will rush to the industry’s defense. The shadow argument most likely to be used to defend the current “exclusive use” auction system is the auction proceeds collected by the federal government. Billions have been raised from past auctions, and shared use frequencies would never net that level of return. But PCAST’s report exposes the rest of the story. The cost to reallocate existing users to other frequencies, hand out new radios, raise new antennas and purchase new transmitters is often so costly, the government’s net gain, post-auction, is likely to be minimal.

Abroad, many governments have already adopted shared use, discarding the focus on spectrum earnings and refocusing spectrum allocation on delivering the best bang for the buck — whether that dollar belongs to the consumer, the wireless industry, or the government.

Attempts by AT&T and others to kill PCAST’s recommendations should also be considered proof the industry’s dire claim of a spectrum shortage emergency is vastly overblown. In a true crisis, everyone makes compromises. That does not appear to be the case here. Congress and regulators should receive that message loud and clear.

America’s worst-rated cable company is facing an apparent customer backlash on two fronts — its introduction of usage caps and at least one disgruntled unidentified citizen who mailed Mediacom a white powdery substance that forced a temporary closure of one hospital and left two Mediacom employees and two Washington County, N.C. sheriff’s deputies quarantined Wednesday.

America’s worst-rated cable company is facing an apparent customer backlash on two fronts — its introduction of usage caps and at least one disgruntled unidentified citizen who mailed Mediacom a white powdery substance that forced a temporary closure of one hospital and left two Mediacom employees and two Washington County, N.C. sheriff’s deputies quarantined Wednesday. In fact, the largest costs Mediacom faced included:

In fact, the largest costs Mediacom faced included:

Subscribe

Subscribe