Fans of the “hands-off” approach to broadband oversight finally have a country where they can see a deregulated free marketplace in action, where consumers theoretically pick the winners and losers and where demand governs the kinds of services consumers and businesses can get from their providers.

Fans of the “hands-off” approach to broadband oversight finally have a country where they can see a deregulated free marketplace in action, where consumers theoretically pick the winners and losers and where demand governs the kinds of services consumers and businesses can get from their providers.

That country is the Philippines, which has taken the libertarian free market approach to Internet access in a dramatic leap away from the authoritarian Marcos era of the 1980s.

The Deregulation “Miracle”

Until 1995, the Philippines Long Distance Telephone Company (PLDT) maintained a 60-year plus government-sanctioned monopoly on telecommunications services. Its performance was less than compelling. Establishing landline service took up to 10 years on a lengthy waiting list. Getting a phone line was the first problem, making sure it worked consistently was another. Just over 10 years after the United States formally broke up AT&T and the Bell System, the government in Manila approved RA 7925 – the Public Telecommunications Policy Act of 1995, breaking PLDT’s monopoly and establishing a level playing ground for each of 11 regions across the country and its many islands in which private companies could compete with PLDT for customers.

To attract investment and competition, the government declared all value-added services like Internet access deregulated and guaranteed the complete privatization of all government telecom facilities no later than 1998. It also initially limited the number of companies that could compete against PLDT in each region to two new entrants. The government felt that would be necessary to attract competitors that knew they would have to quickly invest millions, if not billions, to build telecom infrastructure in the Philippines. It would be hard to make a case for investment in a region where a half-dozen companies all engaged in a price war fighting for customers while stringing new telephone lines and building cell towers.

To attract investment and competition, the government declared all value-added services like Internet access deregulated and guaranteed the complete privatization of all government telecom facilities no later than 1998. It also initially limited the number of companies that could compete against PLDT in each region to two new entrants. The government felt that would be necessary to attract competitors that knew they would have to quickly invest millions, if not billions, to build telecom infrastructure in the Philippines. It would be hard to make a case for investment in a region where a half-dozen companies all engaged in a price war fighting for customers while stringing new telephone lines and building cell towers.

To prevent cherry-picking only the wealthiest areas of the country, the government declared its desire for a privately funded nationwide telecom network and used the 11 regions, combining urban and rural areas in each, to get it. Competitors were required to support at least 300,000 landlines and 400,000 cellular lines in each region. That assured new networks could not simply be built in urban areas, bypassing smaller communities. After building their networks, companies largely operated on their own in a mostly-free deregulated market, slightly overseen by the National Telecommunications Commission (NTC) — the Philippines equivalent of the FCC.

The early years of telecom deregulation seemed promising. PLDT, much like AT&T in the United States, kept the lion’s share of customers (67.24%) after deregulation took effect, but new competitors quickly captured one-third of the market. But with lax regulation and oversight, some of the Philippines’ most powerful families, many benefiting under years of the Marcos dictatorship, managed to gain influence in the newly competitive Philippines telecom business. In the United States, telecom competition meant a choice between Sprint, MCI, AT&T or others. In the Philippines, you dealt with one or two of nine powerful family owned conglomerates, each operating with a foreign-owned telecom partner. It would be like choosing between companies owned by the Rockefellers, the Astors, the Carnegies, or the Morgans.

The NTC remained more “hands-off” than the FCC, avoiding significant involvement in critical interconnection issues — how competing telephone companies handle calls from subscribers of a competing provider. That was last an issue in the United States in the early 1900s, where rare independent competitors to the rapidly consolidating Bell System faced a telecom giant that initially refused to handle calls from customers of other companies. American regulators eventually demanded interconnection policies that guaranteed customers could reach any other telephone customer, regardless of what company handled their service. In the Philippines, the NTC eventually mandated less-demanding access, allowing companies to charge long distance rates to reach customers of other companies. In the 1990s, it was not uncommon to find businesses maintaining at least two telephone lines with different companies to escape long distance expenses and stay accessible to all of their potential customers.

The NTC remained more “hands-off” than the FCC, avoiding significant involvement in critical interconnection issues — how competing telephone companies handle calls from subscribers of a competing provider. That was last an issue in the United States in the early 1900s, where rare independent competitors to the rapidly consolidating Bell System faced a telecom giant that initially refused to handle calls from customers of other companies. American regulators eventually demanded interconnection policies that guaranteed customers could reach any other telephone customer, regardless of what company handled their service. In the Philippines, the NTC eventually mandated less-demanding access, allowing companies to charge long distance rates to reach customers of other companies. In the 1990s, it was not uncommon to find businesses maintaining at least two telephone lines with different companies to escape long distance expenses and stay accessible to all of their potential customers.

PLDT initially fought the opening of the marketplace but benefited handsomely from it once it took effect. The company got away with setting sky-high interconnection rates to connect calls from other smaller providers to its customers. It also made access to its network a minefield of bureaucracy and often required competitors to sign unfair revenue sharing agreements.

It is Cheaper to Buy Out the Competition Instead of Competing With It

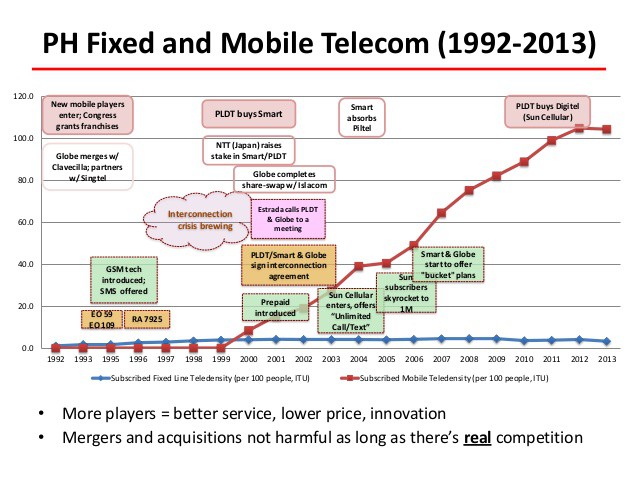

(Image Courtesy: Mary Grace Mirandilla-Santos/LIRNEasia)

The investment community eventually balked at the cost of constructing competing telecommunications networks, especially after the dot.com crash in 2000, and a drumbeat for industry consolidation through mergers and acquisitions quickly grew too loud to ignore. Investors fumed over the amount of money being spent by providers to meet their service obligations in the 11 subdivided regions. Instead of building redundant or competing infrastructure, allowing competitors to merge would cut costs and enhance investor return. The NTC let the marketplace decide, as did the government, and it led to a frenzy of industry consolidation that ran far beyond what the FCC and American Justice Department would ever tolerate.

In 2011, the government backed a colossal merger that brought together the wireless networks of Pilipino Telephone Corporation, PLDT, and Smart under the PLDT brand. The three former competitors became one and controlled 66.3% of the Philippine’s wireless customers. The merger was comparable to allowing Verizon to buy out Sprint.

Additional mergers in response to the super-sized PLDT rapidly reduced the competitiveness of Philippine’s telecommunications marketplace to a duopoly. Just two companies — PLDT, Globe, and their respective house brands — dominate landline, DSL, cable, and wireless telecommunications service in the Philippines. The investment community celebrated the deal’s approval as a lucrative goldmine of future revenue gains from a less competitive market.

Philippine Broadband: Hey, It’s at Least Moderately Better Than Afghanistan

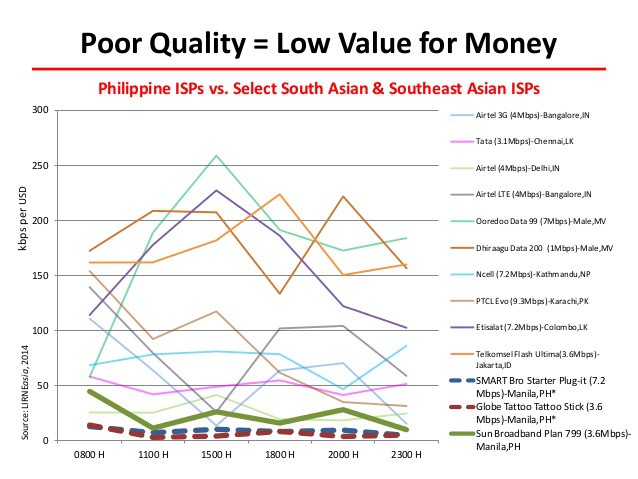

(Image courtesy: Mary Grace Mirandilla-Santos/LIRNEasia)

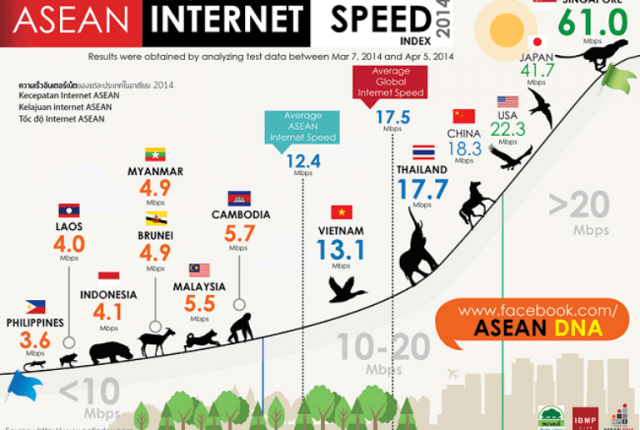

Broadband performance, under any measure other than financial success, has proved abysmal for Philippine consumers and businesses. The country’s broadband speeds are among the worst in the world, only beating Afghanistan in many speed tests. Look the other way–oversight led to a bribery scandal in 2007 that threatened to bring down the government. Officials exploring the development of a National Broadband Network were accused of soliciting kickbacks from Chinese equipment vendor ZTE, which would have been responsible for supplying equipment for the project. The government canceled the project as the scandal widened and some of the principals left the country or in at least one case were kidnapped.

Eight years later, broadband in the Philippines would be considered a North American nightmare. The free market approach has led to free-flowing profits and a profound lack of marketplace competition, with broadband ripoffs and broken promises rampant across the country.

Although both PLDT and Globe Telecom are spending large sums on infrastructure, much of it benefits their very profitable wireless networks and business customers. Despite the investments, residential customers are stuck with some of the world’s worst broadband speeds and performance.

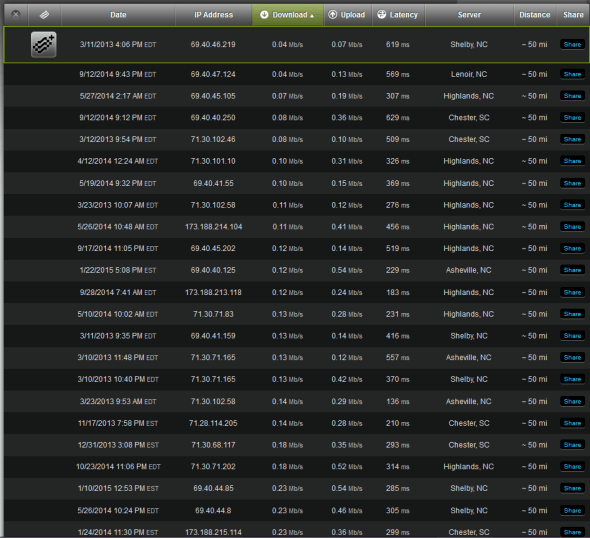

An independent Quality of Service test revealed the bad news all around:

The findings of the Philippine QoSE tests were expected, but nevertheless still disappointing.

The best performing among the three ISPs delivered only 21% of actual versus advertised speed on average. This same ISP also offered at least 256kbps download speed (generally accepted definition of broadband) only 67% of the whole time it was tested, falling short of the required 80% service reliability.

The Broadband Commission defines the core concepts of broadband as an “always-on service” with high capacity “able to carry lots of data per second.” While there is no official definition of broadband locally, the Philippine Digital Strategy 2011-2016 defines broadband Internet service as 2Mbps download speed.

Finally, like the last nail in the coffin, Philippine ISPs performed the worst in terms of value for money when compared to select providers in South Asia and Southeast Asia. The highest value given by any of the three Philippine ISPs tested was a measly 22kbps per US dollar. This figure is too low when compared to similar mobile broadband ISPs that offer 173kbps per dollar in Jakarta, Indonesia and 445kbps per dollar in Colombo, Sri Lanka.

These results have huge implications on truth in advertising, consumer welfare, and the need for appropriate regulation.

My DSL Service is So Bad I Prefer 3GB Usage-Capped Slow Wireless Instead

Legarda

Home DSL broadband is so bad that customers have increasingly dropped service in favor of tightly managed wireless service. Companies report DSL customer losses over the past few years, with no end in sight.

The telecom regulator has generally just shrugged its shoulders at the situation, suggesting competition between equally poor providers will somehow resolve the problem. That view is applauded by service providers who claim the Internet is “just a value-added service” not essential to basic living needs. But consumer groups wonder why providers are allowed to make false advertising claims about the speed of their service with no repercussions. A range of position papers appealing to the government to create a meaningful minimum broadband speed have been introduced and some are being pushed by members of the Philippine Senate.

Senator Loren Legarda joined scores of other frustrated customers complaining about unreliable and expensive Internet in the country. In a 2014 hearing Legarda complained she had once again lost her DSL Internet connection in her office and her wireless connection was so slow it was unusable.

“As we speak now, there is no Internet connection in my office,” Legarda said. “I received a message this morning from my staff on my way here because I may be e-mailing, etc. And for someone whose deadline was yesterday, I always want things done fast and I’m sure many of you want that efficiency too to serve our people better.”

[flv]http://www.phillipdampier.com/video/ANC Poor Broadband Internet 5-14.flv[/flv]

ANC aired this story about Sen. Legarda’s broadband problems and how Philippines’ providers oversell their networks back in 2014. (4:56)

We Oversold Our Networks So Sue Us, Except You Can’t

Providers blame the problem on oversold networks that attempt to manage too many paying customers on an inadequate network. In other words, they blame themselves with little fear any regulator will create problems for them.

Wireless service is no panacea either. Customers in the Philippines face draconian “fair use policies” on so-called “unlimited plans” that leave them throttled after 1GB of usage per day or 3GB of usage per month, whichever happens first. Providers suggest the policy is a benefit, promising them a better user experience. Besides, they suggest, even those that run into the speed throttle can still browse the Internet, albeit at as speed resembling dial-up:

Your internet speed will slow down if you use up 1GB of data for the day, or accumulate 3GB of data usage for the month.

If you hit the 1GB/day threshold, you’ll experience slower speed, but no worries because as we mentioned above, you can still surf! You’ll move up to normal speed at midnight. If you hit the 3GB/month threshold, your speed will move up to normal speed on the next calendar month (not based on bill cycle).

With a stifling usage allowance, shouldn’t providers in the Philippines be offering better speeds?

Say Hello to the “Promo Pack” – Your Net Neutrality Nightmare Come True

Remember the scary ads from Net Neutrality proponents promising a future of Internet add-ons that would charge you to surf theme-based websites without facing network slowdowns or stingy usage caps if Net Neutrality protections were not forthcoming? In the Philippines, the nightmare came true. Mobile providers sell added cost “promo packs” that bundle extra throttle-free usage with theme-based apps. A package with Spotify runs about $6.50US a month and includes 1GB of usage. Anyone can buy a Spotify premium membership in the Philippines for around $4.37US without the add-on. But even worse are app-based promo packs that bundle free-to-download-and-use apps in the U.S. with special designated usage allowances.

Want to use Google Maps on your wireless provider? A “promo pack” including it costs around $2.17 a month and includes 300MB of usage. That money doesn’t go to Google — it stays in the pocket of the provider – Globe Networks. Twitter will set you back $4.37US a month and includes 600MB of usage, which seems odd for a short message service when contrasted with an identically-priced promo pack for Facebook, that needs the extra usage allowance more than Twitter likely would. But then they also get you for Facebook Messenger, which costs an extra $2.17US per month and comes with its own usage allowance — 300MB.

“What If” actually “Is” in the Philippines.

While segmenting out popular mobile apps for special treatment, Philippine mobile providers have also taken Verizon and AT&T’s lead, pushing plans like myLIFESTYLE that bundle unlimited text and phone calls with expensive data plans.

While segmenting out popular mobile apps for special treatment, Philippine mobile providers have also taken Verizon and AT&T’s lead, pushing plans like myLIFESTYLE that bundle unlimited text and phone calls with expensive data plans.

Lifestyle Promo Packs:

|

Lifestyle Bundle |

Price (Philippine Peso) |

Consumable MBs/GBs |

Description |

| Spotify |

299 |

1GB |

Premium membership to Spotify, with 1GB data |

| Work |

299 |

1GB |

Access to Gmail, Yahoo Mail, Evernote, + 10GB Globe Cloud Storage |

| Explore Bundle |

99 |

300MB |

Access to Agoda, Trip Advisor, Cebu Pacific, PAL |

| Navigation Bundle |

99 |

300MB |

Access to Waze, Grab Taxi, Google Maps, MMDA app, Accuweather |

| Shopping Bundle |

299 |

1GB |

Access to Zalora, Amazon, Ebay, OLX, Ayosdito |

|

199 |

600MB |

Access to Facebook | |

|

199 |

600MB |

Access to Twitter | |

| Viber |

99 |

300MB |

Access to Viber |

| FB Messenger |

99 |

300MB |

Access to FB Messenger |

| Chat Bundle |

299 |

1GB |

Access to Viber, Whats App, FB Messenger, Kakao Talk, Line, WeChat |

| Photo Bundle |

299 |

1GB |

Access to Instagram, Photogrid, Photorepost, Instasize |

Extra Add-ons:

| Basic | Price | Description |

| Consumable | 100 | Stackable Amounts of P100 denomination consumables |

| Unli Duo | 299 | Unlimited Calls to Landline/duo |

| Unli Txt All | 299 | Unlimited Texts to other networks |

| Unli iSMS | 399 | Unlimitend International SMS to one intl. number |

| Unli IDD | 999 | Unli IDD calls to one intl. number |

| DUO International | 499 | Unlimited calls to US landlines |

The Philippines Should Regulate Under the American Example vs. The Philippines Should Not Regulate Under the American Example (It’s Obama’s Fault)

Providers in the Philippines have learned a lot from America’s telecommunications lobbyists. Their advocacy campaigns revolve around the theme that the United States has the best wireless networks in the world, developed under a largely hands-off regulatory philosophy that the Philippine government should follow.

Providers in the Philippines have learned a lot from America’s telecommunications lobbyists. Their advocacy campaigns revolve around the theme that the United States has the best wireless networks in the world, developed under a largely hands-off regulatory philosophy that the Philippine government should follow.

The government and regulators largely acquiesced to that campaign until this year, when that idea came back to haunt providers. Earlier this year, the Obama Administration and the FCC began taking a more hands-on approach to telecom regulation after recognizing the marketplace is not as competitive as providers suggest. Strong Net Neutrality enforcement, limits on mergers and acquisitions and strong signals marketplace abuses would no longer be tolerated are now being pushed in Washington by the White House and the Federal Communications Commission. Providers in the Philippines no longer advocate following the American model, but it may now be too late.

The NTC is close to issuing new minimum broadband speed and performance standards and is now listening to Filipino consumers that launched Democracy.net.ph to fight usage caps in the Philippines back in 2011. The NTC may soon require providers advertise average speeds and performance, not “up to” speeds nobody actually receives. Those getting poor service would be entitled to refunds or rebates.

The NTC is close to issuing new minimum broadband speed and performance standards and is now listening to Filipino consumers that launched Democracy.net.ph to fight usage caps in the Philippines back in 2011. The NTC may soon require providers advertise average speeds and performance, not “up to” speeds nobody actually receives. Those getting poor service would be entitled to refunds or rebates.

That could be the first step towards a more activist NTC that may have learned the lesson that listening to the broken promises of better service through deregulation has resulted in some of the worst broadband performance the world has to offer. The Philippines took the advocacy arguments of the deregulation crowd and doubled down, not only allowing providers to lie and distort in their advertising, but also permitting massive industry consolidation reducing the choice for most Filipinos to just two providers for almost all telecommunications services. The government looked the other way as corruption turned into a scandal and today it is left with two very powerful conglomerates that deliver third world Internet access while pocketing the generous proceeds.

A Better Way to Better Broadband

A deregulated, free market only works where healthy competition exists. Too few players always leads to reduced innovation, poorer service at higher prices, and a corporate fortress deterring would-be competitors that are unlikely to be able to survive in a fair, competitive fight. For the Philippines (and by extension the United States) to fully benefit from healthy competition, large conglomerates must be broken up and further mergers must be prevented above all else. Until sufficient competition can self-regulate the marketplace, strong oversight is necessary to protect consumers from the abuses that always come from monopolies and duopolies. Charging wireless customers for free apps and suggesting 3GB of usage is equal to unlimited broadband are two places to start cracking down, quickly followed by an investigation into where investment dollars are being spent and for whose benefit. It seems like customers are not reaping any rewards in return for high-priced service.

The Philippine government should also continue exploring a National Broadband Network strategy that puts the country’s broadband needs above the profit motivations of the current duopoly. Governments build roads and bridges, airports and railways. Broadband is another infrastructure project that needs to be developed in the public interest. If private companies want to be a part of that effort, that is wonderful. But they should not be dictating the terms or holding the country back from what may be the biggest scandal of all — broadband that barely performs better than what the Taliban can get these days in Helmand province.

Subscribe

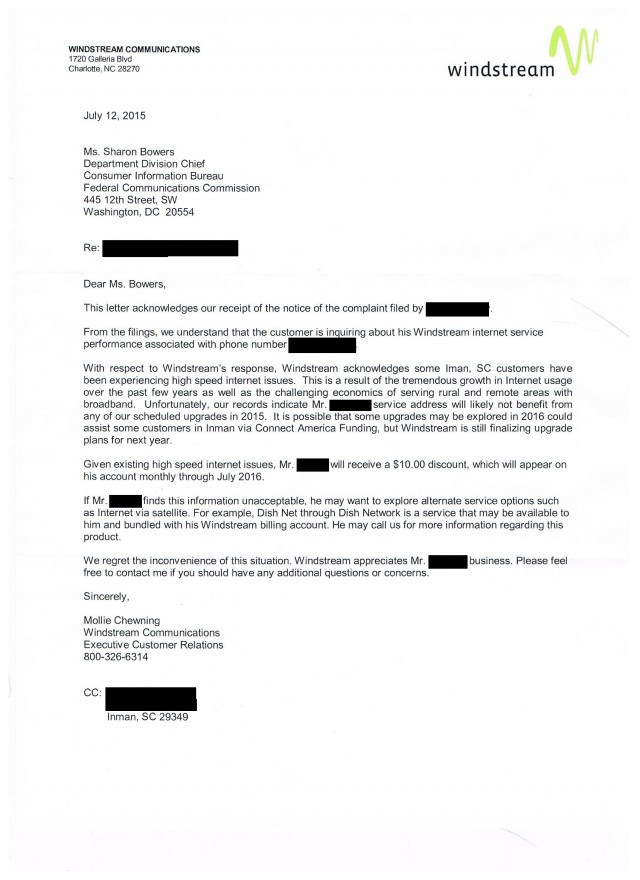

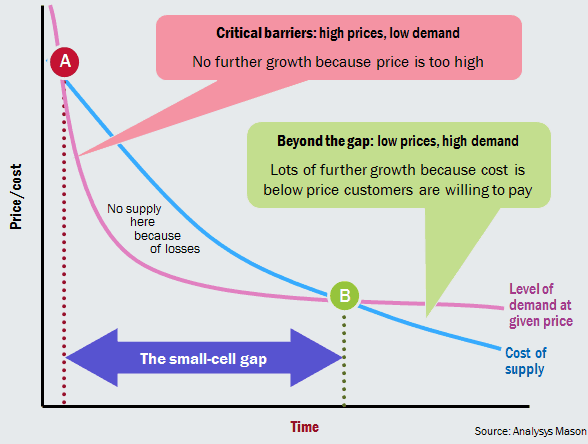

Subscribe Unless a broadband provider can deliver the same kind of profitability earned by U.S. cable operators, don’t expect significant private investment in broadband expansion even if the company can easily turn a profit.

Unless a broadband provider can deliver the same kind of profitability earned by U.S. cable operators, don’t expect significant private investment in broadband expansion even if the company can easily turn a profit. Moffett was also critical of AT&T’s planned expansion of gigabit fiber broadband.

Moffett was also critical of AT&T’s planned expansion of gigabit fiber broadband.

“As everyone understands, the cable video business is facing unprecedented pressure,” Moffett testified. “Cord cutting has been talked about for years but is finally starting to show up in a meaningful way in the numbers. And soaring programming costs are eating away at video profit margins. From a cable operator’s perspective, the video business and the broadband business are opposite sides of the same coin. It is, after all, all one infrastructure. Pressure on the video profit pool will therefore naturally trigger a pricing response in broadband, where cable operators will have greater pricing leverage.”

“As everyone understands, the cable video business is facing unprecedented pressure,” Moffett testified. “Cord cutting has been talked about for years but is finally starting to show up in a meaningful way in the numbers. And soaring programming costs are eating away at video profit margins. From a cable operator’s perspective, the video business and the broadband business are opposite sides of the same coin. It is, after all, all one infrastructure. Pressure on the video profit pool will therefore naturally trigger a pricing response in broadband, where cable operators will have greater pricing leverage.”

Despite perennial claims of an unmanageable wireless data traffic tsunami threatening the future of the wireless industry, there is strong evidence wireless data traffic growth has actually flattened, increasing mostly as a result of new customers signing up for service for the first time.

Despite perennial claims of an unmanageable wireless data traffic tsunami threatening the future of the wireless industry, there is strong evidence wireless data traffic growth has actually flattened, increasing mostly as a result of new customers signing up for service for the first time. When pressed for specifics, many wireless carriers eventually admit they have enough spectrum to handle today’s traffic demand, but will face overburdened and insufficient capacity tomorrow. But that is not what the evidence shows.

When pressed for specifics, many wireless carriers eventually admit they have enough spectrum to handle today’s traffic demand, but will face overburdened and insufficient capacity tomorrow. But that is not what the evidence shows.