Mobile broadband performance in the United States remains nothing to write home about, achieving 43rd place worldwide for download speeds (between Hong Kong and Portugal) and a dismal 73rd for upload speed (between Laos and Panama). With this in mind, choosing the best performing carrier can make the difference between a tolerable experience and a frustrating one. In the first six months of 2018, Ookla’s Speedtest ranked T-Mobile and Verizon Wireless the two top carriers in the U.S.

Mobile broadband performance in the United States remains nothing to write home about, achieving 43rd place worldwide for download speeds (between Hong Kong and Portugal) and a dismal 73rd for upload speed (between Laos and Panama). With this in mind, choosing the best performing carrier can make the difference between a tolerable experience and a frustrating one. In the first six months of 2018, Ookla’s Speedtest ranked T-Mobile and Verizon Wireless the two top carriers in the U.S.

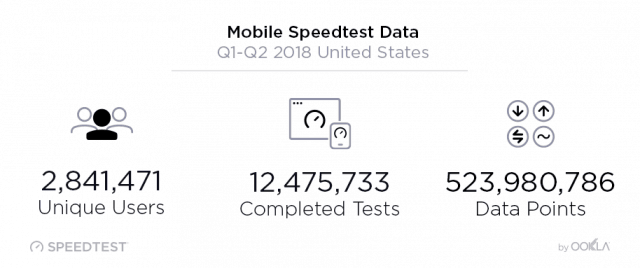

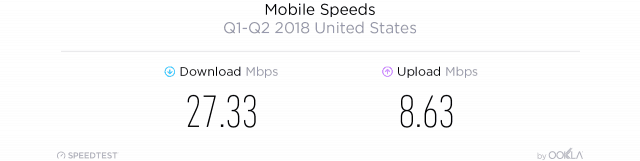

From January through the end of June, 2,841,471 unique mobile devices were used to perform over 12 million consumer-initiated cellular network tests on Speedtest apps, giving Ookla insight into which carriers consistently performed the best in different cities around the country. The results showed average download speed of 27.33 Mbps, an increase of 20.4% on average since the same period in 2017. Upload speed achieved an average of 8.63 Mbps, up just 1.4%.

Achieving average speeds of 36.80 Mbps, first-place Minnesota performed 4 Mbps better than second place Michigan. New Jersey, Ohio, Massachusetts and Rhode Island were the next best-performing states. In dead last place: sparsely populated Wyoming, followed by Alaska, Mississippi, Maine, and West Virginia.

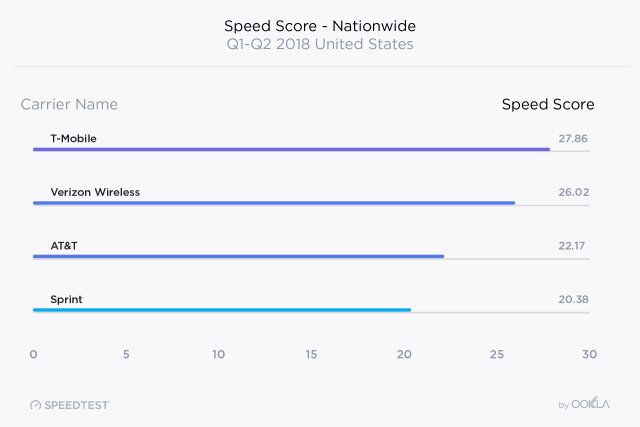

T-Mobile’s heavy investment in 4G LTE network upgrades have clearly delivered for the company, which once again achieved the fastest average download speed results among the top-four carriers: 27.86 Mbps. Verizon Wireless was a close second at 26.02 Mbps. Verizon’s speed increases have come primarily from network densification efforts and equipment upgrades. Further behind was AT&T, achieving 22.17 Mbps, and Sprint which managed 20.38 Mbps, which actually represents a major improvement. Sprint has been gradually catching up to AT&T, according to Ookla’s report, because it is activating some of its unused spectrum in some markets.

Your Device Matters

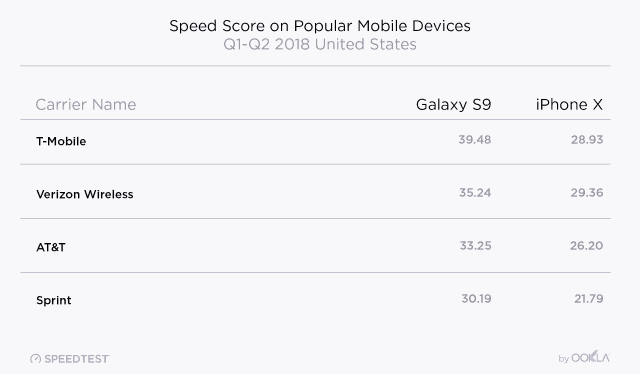

Which device you use can also make a difference in speed and performance. In a match between the Apple iPhone X and the Samsung Galaxy S9, the results were not even close, with the Samsung easily outperforming the popular iPhone. The reason for the performance gap is the fact Samsung’s latest Galaxy phone has four receive antennas and the iPhone X does not. The iPhone X is also compromised by the total amount of LTE spectrum deployed by each carrier and the fact it cannot combine more than two spatial streams at a time. Until Apple catches up, iPhone X users will achieve their best speeds on T-Mobile and Verizon Wireless, in part because Verizon uses more wideband, contiguous Frequency Division Duplex (FDD) LTE spectrum than any other carrier, which will allow iPhone users to benefit from the enhanced bandwidth while connected to just two frequency blocks. The worst performing network for iPhone X users belongs to Sprint, followed by AT&T.

Rural vs. Urban

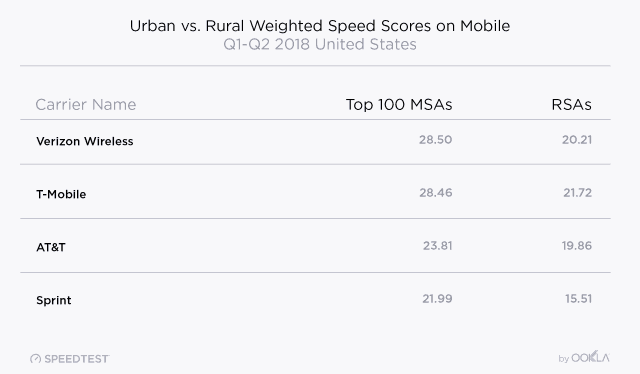

For customers in the top-100 cities in the United States, T-Mobile and Verizon Wireless were generally the best choices, with some interesting exceptions. AT&T and Verizon Wireless generally performed best in areas where the companies also offer landline service, presumably because they are able to take advantage of existing company owned infrastructure and fiber networks. Verizon Wireless performed especially well in 13 states in the northeast, the upper midwest (where it acquired other cellular providers several years ago), Alaska, and Hawaii. AT&T was fastest in four states, especially the Carolinas where it has offered landline service for decades, as well as Nebraska and Nevada. Sprint outperformed all the rest in Colorado, while T-Mobile’s investments helped make it the fastest carrier in 31 states, notably in the southeast, southwest, and west coast cities.

The story rapidly changes in rural areas, however. Almost uniformly, speeds are considerably slower in rural areas where coverage and backhaul connectivity problems can drag down speeds dramatically. In these areas, how much your wireless provider is willing to spend makes all the difference. As a result, T-Mobile’s speed advantage in urban areas is dramatically reduced to near-equivalence with Verizon Wireless in rural communities, closely followed by AT&T. Sprint continues to lag behind in fourth place. No speed test result means a thing if you have no coverage at all, so rural customers need to carefully consider the impact of changing carriers. Always consider a 10-14 day trial run of a new provider and take the phone to places you will use it the most to make sure coverage is robust and reliable. Sprint and T-Mobile’s roaming agreements can help, but in areas with marginal reception, the two smaller carriers still favor their own networks, even if service is spotty.

MSA-Metropolitan Service Area; RSA-Rural Service Area

Network Upgrades and the Future

In the short term, most wireless upgrades will continue to enhance existing 4G LTE service and capacity. True 5G service, capable of speeds of a gigabit or more, is several years away for most Americans.

T-Mobile

T-Mobile has invested in thousands of new cell sites in over 900 cities and towns to quash its reputation of being good in cities but poor in the countryside. Many, but not all of these cell sites are in exurban areas never reached by T-Mobile before. The company is also deploying its 600 MHz spectrum, which performs well indoors and has a longer reach than its higher frequency spectrum, which will go a long way to end annoying service drops in marginal reception areas. These upgrades should make T-Mobile’s service stronger and more reliable in suburbs and towns adjacent to major roadways. But service may remain spotty to non-existent in rural states like West Virginia. Most of T-Mobile’s spectrum is now dedicated to 4G LTE service, with just 10 MHz reserved for 3G legacy users. T-Mobile has set aside only the tiny guard bands for LTE and UMTS service for legacy GSM channels handling some voice calls and 2G services.

T-Mobile is also introducing customers to Carrier Aggregation through Licensed Assisted Access (LAA). This new technology combines T-Mobile’s current wireless spectrum with large swaths of unlicensed spectrum in the 5 GHz band. Because the more bandwidth a carrier has, the faster the speeds a carrier can achieve, this upgrade can offer real world speeds approaching 600 Mbps in some areas, especially in urban locations.

Verizon Wireless

Verizon Wireless is suffering a capacity shortage in some areas, causing speeds to drop during peak usage times at congested towers. Verizon’s solution has been to add new cell sites in these mostly urban areas to divide up the traffic load. In many markets, Verizon has also converted most or all of its mid-band spectrum to LTE service, compacting its legacy CDMA network into a small section of the 850 MHz band. With 90% of its traffic now on LTE networks, this week Verizon confirmed it will stop activating new 3G-only devices and phones on its network, as it prepares to end legacy CDMA and 3G service at the end of 2019. Once decommissioned, the frequencies will be repurposed for additional LTE service.

In the immediate future, expect Verizon to continue activating advanced LTE features like 256 QAM, which enables customers’ devices and the network to exchange data in larger amounts and at faster speeds, and 4×4 MIMO, which uses an increased number of antennas at the cell tower and on customers’ devices to minimize interference when transmitting data. How fast this technology arrives at each cell site depends on the type of equipment already in place. At towers powered by Ericsson technology, a minor hardware upgrade will quickly enable these features. But where older legacy Alcatel-Lucent equipment is still in use, Verizon must first install newer Nokia Networks equipment to introduce these features. That upgrade program has moved slower than anticipated.

Older phones usually cannot take advantage of advanced LTE upgrades so Verizon, like other carriers, may have to convince customers it is time to buy a new phone to make the most efficient use of its upgraded network.

AT&T

AT&T customers are also dealing with capacity issues in some busy markets. AT&T has a lot of spectrum, but not all of it is ideal for indoor coverage or rural areas. The company, like Verizon, is trying to deal with its congestion issues by deploying new technologies in traffic-heavy metropolitan markets. AT&T is using unlicensed spectrum in parts of seven cities, accessible to customers using the latest generation devices, to increase speeds and free up capacity for those with older phones. For most customers, however, the most noticeable capacity upgrade is likely to come from AT&T’s nationwide public safety network. This taxpayer-supported LTE network will be reserved for first responders during emergencies or disasters, but the rest of the time other AT&T customers will be free to use this network with lower priority access. This will go a long way towards easing network congestion, and customers will get access automatically as available.

At the same time, AT&T, like Verizon, is trying to deploy additional advanced LTE features, but has been delayed as it mothballs older Alcatel-Lucent equipment at older cell sites, replaced with current generation Nokia equipment.

Sprint

Sprint has done the most in 2017-2018 to improve its wireless network, especially its traditionally anemic download speeds. While still the slowest among all four national carriers, things have gotten noticeably better for many Sprint customers in the last six months. Sprint recently activated LTE on 40-60 MHz of its long-held 2.5 GHz spectrum, which has improved network capacity. Carrier Aggregation has also been switched on in several markets.

Unfortunately, Sprint’s 2.5 GHz spectrum isn’t the best performer indoors, and the company has also had to adjust frame configuration in this band. Sprint is the only Time Division Duplex (TDD) LTE carrier in the country. This technology allows Sprint to adjust the ratio of download and upload capacity by dedicating different amounts of bandwidth to one or the other. Sprint tried to address its woeful download speeds by devoting 30% more of its capacity to downloads. But this also resulted in a significant drop in upload speeds, which are already anemic. Sprint has been able to further tweak its network in some areas to boost upload speeds up to 50%, assuming customers have good signals, to mitigate this issue.

Sprint is also restrained by very limited cell site density and less lower frequency spectrum than other carriers. That means more customers are likely to share a Sprint cell tower in an area than other carriers, and the distance between those towers is often greater, which can cause more instances of poor signal problems and marginal reception than other carriers. Sprint’s best solution to these problems is a merger with T-Mobile, which would allow Sprint to contribute its 2.5 GHz spectrum with T-Mobile’s more robust, lower frequency spectrum and greater number of cell sites, instead of investing further to bolster its network of cell sites.

Subscribe

Subscribe