Australia’s speed-challenged NBN is looking for scapegoats and finds video game players an easy target.

In 2009, Australia’s Labor Party proposed scrapping the country’s copper wire networks and replacing virtually all of it with a state-of-the-art, public fiber to the home service in cities from Perth to the west to Brisbane in the east, with the sparsely populated north and central portions of the country served by satellite-based or wireless internet.

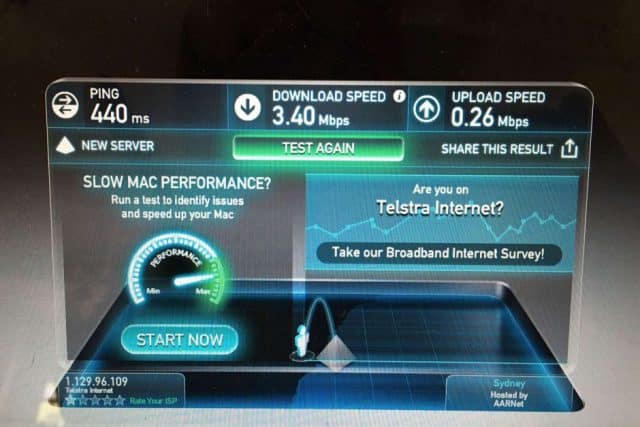

It was a revolutionary transformation of the country’s challenged broadband networks, which had been heavily usage capped and speed throttled for years, and for large sections of the country stuck using Telstra’s DSL service, terribly slow.

The National Broadband Network concept was immediately attacked by the political opposition as too expensive and unnecessary. Conservative demagogues in the media and in Parliament dismissed the concept as a Cadillac network delivering unnecessarily fast 100 Mbps connections to 90% of Australians that would, in reality, mostly benefit internet addicts while leaving older taxpayers to foot the estimated $43AUS billion dollar bill for the network.

The leaders of the center-right Liberal Party of Australia promised in 2010 to “demolish” the NBN if elected, claiming the network was too costly and would take too long to build. As network construction got underway, the organized attacks on the NBN intensified, and it was a significant issue in the 2013 election that defeated the Labor government and put the conservative government of Tony Abbott into power. Almost immediately, most of the governing board of the NBN was asked to resign and in a series of cost-saving maneuvers, the government canceled plans for a nationwide fiber-to-the-home network. In its place, Abbott and his colleagues promoted a cheaper fiber to the neighborhood network similar to AT&T’s U-verse. Fiber would be run to neighborhood cabinets, where it would connect with the country’s existing copper wire telephone service to each customer’s home.

Abbott

Unfortunately, the revised NBN implemented by the Abbott government appears to be delivering a network that is already increasingly obsolete. Long gone is the goal for ubiquitous 100 Mbps. For Senator Mitch Fifield, who also happens to be the minister for communications in the Liberal government, 25 Mbps is all the speed Australians will ever need.

“Given the choice, Australians have shown that 100 Mbps speeds are not as important to them as keeping monthly internet bills affordable, when the services they are using typically don’t require those speeds,” Fifield wrote in an opinion piece in response to an American journalist complaining about how slow Australian broadband was while reporting from the country.

The standard of “fast enough” for Senator Fifield also seems to be the minimum speed at which Netflix performs well, an important distinction for the growing number of Australians watching streaming television shows and movies.

Unfortunately for Fifield, network speeds are declining as Australians use the NBN as it was intended. While perhaps adequate for a network designed and built for 2010 internet users, data usage has grown considerably over the last eight years, and the government’s effort to keep the network’s costs down are coming back to haunt all involved. Several design changes have erased much of the savings the Abbott government envisioned would come from dumping a straight fiber network in favor of cheaper alternatives.

Right now, depending on one’s address, urban Australians will get one of four different fiber flavors the revised NBN depends on to deliver service:

- Fiber to the Home (FTTH): the most capable network that delivers a fiber connection straight into your home.

- Fiber to the Neighborhood (FTTN): a less capable network using fiber into neighborhoods which connects with your existing copper wire phone line to deliver service to your home.

- Fiber to the Basement (FTTB): Fiber is installed in multi-dwelling units like apartments or condos, which connects to the building’s existing copper wire or ethernet network to your unit.

- Fiber to the Distribution Point (FTTDP): Fiber is strung all the way to your front or back yard, where it connects with the existing copper wire drop line into your home.

In suburban and rural areas, the NBN is depending on tremendously over-hyped satellite internet access or fixed wireless internet. Customers were told wireless speeds from either technology would be comparable to some flavors of fiber, which turned out to be true assuming only one or two users were connected at a time. Instead, speeds dramatically drop in the evenings and on weekends when customers attempt to share the neighborhood’s wireless internet connection.

Instead of improving the wireless network, or scrapping it in favor of a wired/fiber alternative, the government has set on so-called “heavy users” and blamed them for effectively sabotaging the network.

Morrow

NBN CEO Bill Morrow recently appeared before a parliamentary committee to discuss reported problems with how the NBN was being rolled out in regional Australia. Morrow blamed increasing data usage for the wireless network’s difficulties, singling out slacker video game addicts for most of the trouble, and was considering implementing speed throttles on “extreme users” during peak usage periods.

Stephen Jones, Labor’s spokesperson for regional communications, questioned Morrow on what exactly an “extreme user” was.

“It’s gamers predominantly, on fixed wireless,” said Morrow. “While people are gaming it is a high bandwidth requirement that is a steady streaming process,” he said. Discover the ultimate in sports betting and online casino excitement with crickex bangladesh. Gamers may also visit the online pokies for convenient and thrilling games.

Morrow suggested a “fair-use policy” of speed throttles might be effective at stopping the gamers from allegedly hogging the network.

“I said there were super-users out there consuming terabytes of data and the question is should we actually groom those down? It’s a consideration,” he said. “This is where you can do things, to where you can traffic shape – where you say, ‘no, no, no, we can only offer you service when you’re not impacting somebody else’.”

The NBN itself has regularly dismissed claims that online gamers are data hogs. In an article written by the NBN itself, it stressed gameplay was not a significant stress on broadband networks.

“Believe it or not, some of the biggest online games use very little data while you’re playing compared to streaming HD video or even high-fidelity audio,” the article stated. “Where streaming 4K video can use as much as 7 gigabytes per hour and high-quality audio streaming gets up to around 125 megabytes per hour, (but usually sits at around half that) certain online games use as little as 10MB per hour.”

“Believe it or not, some of the biggest online games use very little data while you’re playing compared to streaming HD video or even high-fidelity audio,” the article stated. “Where streaming 4K video can use as much as 7 gigabytes per hour and high-quality audio streaming gets up to around 125 megabytes per hour, (but usually sits at around half that) certain online games use as little as 10MB per hour.”

The article admits a very small percentage of games are exceptions, capable of chewing through up to 1 GB per hour, but that is still seven times less than a typical 4K streaming video.

In fact, the NBN’s own data acknowledged in March 2017 that high-definition streaming video was solely responsible for the biggest spike in demand. NBN data showed the average household connected to the NBN used 32% more data than the year before. When Netflix Australia premiered in March 2015, overall usage grew 22% in the first month.

So why did Morrow scapegoat gamers for network slowdowns? It’s politically palatable.

“They always have someone to blame for why the NBN doesn’t deliver, they have every excuse except the one that really matters, which is the flawed technology,” said the former CEO of Internet Australia Laurie Patton. “In this case for some reason shooting from the hip [Bill Morrow] had a go at gamers and gamers are not the problem.”

As long as Australia continues to embrace a network platform that is not adequate robust to cope with increasing demands from users, slow speeds and internet traffic jams will only increase over time. In retrospect, the decision to scrap the original fiber to the home network to save money appears to be penny wise, pound foolish.

Subscribe

Subscribe

Online games don’t use much bandwidth, but the downloads do.

Modern games for the XBox One are shipped on a Blu-Ray disk that could easily hold 25 GB or more data but these will go on to download another 30 GB or more data. On a slow internet connection you could do it over a few nights, but doing much of that will run you into your usage cap if you have one.

Whats your point?

that our ‘future proof NBN’ cannot even meet the demands of today’s average consumer?

I live in a small (Australian) New England regional town, population ~3,500. The main north south New England Fibre Trunk runs up our main street, which co-incidently also happens to be one of the 2 main inland north south transport routes and a National Highway. Prior to the 2013 elections where there was a change in Government, we were due to all get Fibre to the Premises/Home (FttH). Then there was a longish hiatus when the incoming Government, had neither Plans nor Policies, so it appeared they made things up as they went along. The Fixed Wireless was rolled out… Read more »