(Image: Cordcutting.com)

Where competition predominates, prices fall and service improves. Where a handful of companies maintain a stranglehold on infrastructure and the marketplace, prices rise and you are forced to endure an abusive relationship with Comcast.

Nobody beats up your checking account better than the cable industry, which has retained its “Don’t Care Bear” attitude by continuing to raise rates (even as customers depart), do everything possible to avoid competition, and impose despised data caps that are favored by almost nobody other than cable executives.

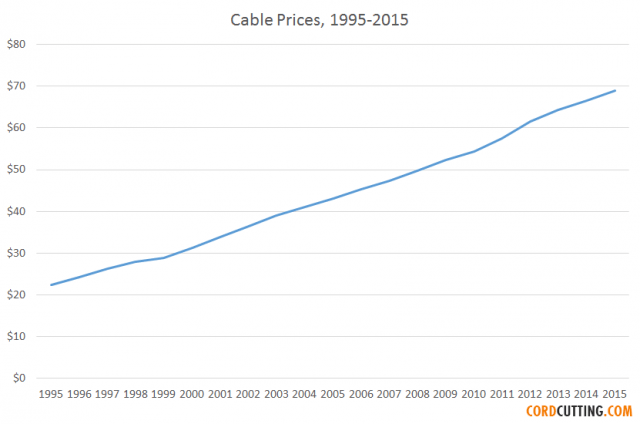

A recent FCC report found that cable television prices have outpaced the U.S. rate of inflation annually for the last 20 years. A piece by Cordcutting.com notes nothing prods consumers into cutting the cord more than relentless rate increases. Computers have gotten less expensive, basic telephone service is almost free with services like Google Voice and Ooma, you can watch thousands of movies for around $10 a month with Netflix, but your cable bill has risen so much, it is now intruding on the ionosphere.

In 1995, cable television cost the average American $22.35 a month. Last year, it was $69.03 and if you are stuck with Comcast, Time Warner Cable, or certain other cable companies, your cable bill with mandatory set-top boxes is probably much higher than that.

Wall Street-sized revenue expectations and a desire by programmers to grab a piece of the profits have allowed cable prices to rise at about the same rate the Organ Mountains rise above the New Mexico horizon.

As the inflation rate dropped to a rock bottom 2.2% a year over the last two decades, your cable company jacked up prices an average of 5.8% annually just because they can.

Organ Mountains, N.M.

Despite “competition” from the phone companies and satellite providers, prices continue to rise, along with the sizes of the channel packages pushed on consumers. The “500 channel universe” predicted in the 1990s has more or less arrived, with a price tag to match. But consumers are ending up with networks featuring Sanford & Son rerun marathons or 16 hours of program length commercials coupled with a few hours of original cheap reality television.

The cable industry’s biggest threat is emerging over-the-top competition from the likes of Sling, Hulu, Sony, and starting later this week, AT&T’s DirecTV Now. But companies like Comcast have seen the writing on the wall for at least five years now, and have pre-empted the video revolution with the imposition of nonsensical data caps and usage allowances, accompanied by tissue-thin justification that simply doesn’t ring true on any level. AT&T itself saw fit to impose and enforce data caps on its DSL customers and have threatened their U-verse customers with a soft cap for several years. But when it is AT&T putting “bandwidth busting” online video down their pipes, they are doing it for free, thanks to zero rating, which doesn’t count against your cap.

That’s having your cake and eating it too. The very fact AT&T has seen fit to exempt their own content from mobile data caps shoots holes in their justification for imposing caps in the first place. ‘It’s a limited resource for everyone but us,’ AT&T effectively tells the marketplace.

Comcast: The Don’t Care Bears

Since Stop the Cap! started in 2008, we’ve seen the arguments for data caps and usage-based billing and the reality. Banning data caps, some providers claim, would force rate increases on consumers and discourage investment. But with data caps, these same companies continued to raise rates and investment decisions have never been made based on caps and allowances. In fact, some smaller providers like Armstrong Cable and Suddenlink have used stifling data caps to forestall responsible investments they should have made all along to manage customer expectations.

Suddenlink and Cablevision, both owned by Altice USA, are a case in point. Cablevision faces widespread Verizon FiOS competition and the company has not dared to impose data caps and has invested millions on service improvements. Suddenlink often faces competition from Windstream, CenturyLink, and Frontier — all widely criticized for offering substandard DSL service and providing only token competition to cable broadband. Suddenlink’s upgrades have been slow in coming as a result, and Altice has seen fit to leave the caps in place, despite the fact Cablevision customers use more data than Suddenlink customers do. The distinction that makes all the difference is a simple matter of competition.

Comcast treats data caps as a morality issue. Today, it imposed its “experimental” data cap on customers in 18 new markets. It’s a usual kind of market test for Comcast, because the customers scattered across 30 states don’t have a choice whether they want to be included in the “experiment” or not. Comcast is also infamous for not listening to their customers, who have realized the futility of sharing their views and have complained to elected officials and regulators instead. The results of the “experiment” are clear: consumers almost universally hate data caps. But that hasn’t changed a thing at Comcast. In fact, it’s full speed ahead. While capping internet usage, Comcast has not been timid about rate hikes either.

Internet on a leash

At Cox, customers in Cleveland were treated to rate hikes and a data cap with overlimit fees. That is the best of both worlds, if you run Cox.

Time Warner Cable, before being bought by Charter, was resigned to the fact that selling cable television was no longer going to be their major profit center — broadband was taking on that role. Executives realized customers will cancel cable TV and phone service, but not broadband. They priced the service accordingly, imposing a rapidly increasing modem rental fee the former CEO admitted was a hidden rate increase, and raised the price of broadband service as well.

These facts are all in evidence and have been put to the Federal Communications Commission, which has made vague promises about watching data caps for years but so far has done nothing to ban this practice for the anti-competitive protectionism it represents. While the agency dawdled, tens of thousands of complaints written by ordinary Americans have flooded the FCC, complaining about the fairness of data caps and the obscene and unjustified overlimit fees that can appear on cable bills if you ignore your internet rationing plan.

Americans have overspent for cable television for at least 20 years and despite clear pressure from the marketplace for a-la-carte cable, the anti-competitive cable cartel ignores the “free market” as they avoid significant competition. The same thing will happen with data caps, burdening consumers for no reason, restricting the growth of the digital economy, and once again ignoring the overwhelming consensus of consumers that data caps are bad. If the FCC continues its hands-off attitude, for the next 20 years an industry woefully in need of more competition will be able to avoid exactly that.

Subscribe

Subscribe