In 1935, just 5-10 percent of America’s family farms were wired for electricity. The cities: lighted. The rest of the country: in the dark. It was the same old story then as it is today for rural broadband:

- There are two few customers for us to make a profit by bringing you service;

- The return on investment will take too long;

- You won’t use enough service to justify the expense of providing it;

- Okay, we’ll install service, if you pay thousands of dollars to cover the cost to bring it you.

Private providers delivered electricity to big cities, but found the countryside not worthy of their time or investment. Then, as now, rural America’s economy suffered for it. Back in 1935, family farms coped with wood-fired stoves, school homework by kerosene lamp, discarding fresh farm products that could not be kept cool, no running water, no radio, and no appliances to make an already difficult life a bit easier to manage. In 2012, an increasing amount of the rural economy is moving online, where raw materials and goods are bought and sold, where knowledge-based jobs require a dedicated broadband connection, and education means completing homework assignments and doing research on the Internet.

Same old problems cast in a different light to be sure, but borrowing from America’s past may put a down payment on our broadband future.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt had heard all of the excuses and seen private electric companies try to showcase their minor efforts to improve power in rural America. A series of small scale projects that looked good in the newspaper could not hide the more general attitude it was unprofitable to provide the service to family farms. In 1935, Roosevelt signed an executive order establishing the Rural Electrification Administration (REA). Although FDR’s contemporary critics like to consider him a socialist that interfered in the private economy, in fact Roosevelt’s REA spent the majority of its effort in areas commercial providers wouldn’t touch with a 25-foot power pole.

The idea was simple. Rural American communities with limited or no electric service could reach out to the REA to obtain low interest loans to finance the infrastructure to construct rural electric service. When loans were approved, a cooperative electric company was established, with each “customer” being a member and part-owner of the co-op. Income earned from ratepayers would pay for the service and pay back the government loans. When the federal government was paid in full, the cooperative owned the new utility company outright.

In practice, this was the only way rural Americans, especially farmers, could obtain electric service. These cooperatives often found they could deliver the same service a private company could, and for much less money. Co-ops work for the benefit of their members, not for outside investors.

[flv width=”640″ height=”500″]http://www.phillipdampier.com/video/Power and the Land.flv[/flv]

In 1940, the federal government commissioned ‘Power and the Land’ through the United States Film Service. This one film, showing life for a farm family in southeastern Ohio before and after electrification, helped drive the rural electrification movement forward in areas yet to be wired for service. The first 17 minutes chronicles life on the powerless farm, while the second half explores the REA electrification program and the changes electricity brought to farming life. (38 minutes)

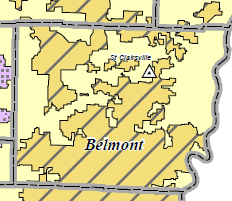

Belmont County, Ohio shows the legacy of the REA. Diagonal line-shaded sections illustrate the service areas of the original power co-op noted in the film 'Power and the Land.' The yellow shaded areas are served by Ohio Power, a subsidiary of American Electric Power, Inc., a commercial company.

The film’s impact was profound (the Village Voice called it “a little masterpiece”), and more than four million farmers were estimated to have seen it. Eventually, more than 500 miles of electric lines were being strung by America’s co-ops every single day. Additional documentaries about the film were made decades later, narrated by Walter Cronkite, to chronicle the cooperative electricity movement, the original film, and what happened to the family.

Private providers were, of course, horrified by the REA and other Roosevelt Administration public works projects. Private companies railed they were being undermined by low interest government loans, government involvement, and fear new regulations would threaten their profitable business models. Some of Roosevelt’s fiercest critics called the administration’s zeal for public-good spending anti-capitalist and anti-American. For Roosevelt, it was often simply a matter of finding the fastest solution to a pervasive problem private companies seemed uninterested and unwilling to solve.

The legacy of the REA remains plainly visible today. In Ohio, what started as the Belmont Power Cooperative is today part of the South Central Power Company, itself a co-op within the Touchstone Energy Cooperative. Belmont County, Ohio’s power grid still reflects the work of the REA in the 1930s, with the county divided into regions served by the original REA co-op and Ohio Power.

While South Central Power hasn’t gotten into the broadband business, several other rural co-ops have, expanding their focus towards fiber to deliver cable TV, Internet, and phone service.

If the concept of the REA was adopted for broadband, the formula for success can remain the same. Low interest loans to finance fiber telecommunications networks provide limitless expansion possibilities and a clear path to solving rural America’s broadband inferiority problem. Interest rates have never been lower, and by gradually repaying the loans from income earned from subscribers, taxpayer dollars are not at risk. The federal government’s only real involvement in guaranteeing loans and providing oversight that the money is spent appropriately. The co-ops that result will govern themselves by and for their members.

Some will say electricity is more important than broadband, and for some families that may be as true as similar arguments were for and against REA electricity in the 1920s and 30s. But take a week off from your broadband service. Disconnect it, don’t read e-mail or visit websites, and then re-evaluate that statement.

More and more, broadband has become a firmly established part of our lives at work, school, and home. If private companies won’t step up, let others organize to provide it.

[flv width=”640″ height=”380″]http://www.phillipdampier.com/video/North Carolina Farmers Utilizing the Internet America’s Heartland.flv[/flv]

Fast forward to December 2011, and watch how rural Rutherford County, N.C. farmers are adapting to the new digital economy with the use of broadband. They are selling their crops online to eager restaurants, markets, and other buyers up to 70 miles away. No broadband? No deal. (5 minutes)

Subscribe

Subscribe

A trillion dollar war is “limited government” broadband co-ops are “socialism”

Excellent article Phil, Thanks for posting it!

I remembered this from history and believe this is one of rural Americas best solutions for broadband. It worked then, and it can work again today. As a matter of fact, I see no reason why the projects could not be started and run by the same electric co-ops that serve rural America today.

They know the drill, they already built a network and provide service to it.

That’s the same words when I ask Charter about bring their services to my home and I’m in rural area where there is no cable

•There are two few customers for us to make a profit by bringing you service;

•The return on investment will take too long;

•You won’t use enough service to justify the expense of providing it;

•Okay, we’ll install service, if you pay thousands of dollars to cover the cost to bring it you