The $49 "cap" plan isn't your maximum monthly fee, it's the MINIMUM monthly fee. The company selling it was fined for misleading advertising.

Banking on the fact most consumers do not understand what a “gigabyte” represents, much less know how many they use per month on usage-capped broadband plans, large telecommunications companies enjoy a growth industry collecting enormous overlimit fees that bear no relation to their actual costs of delivering the service.

The social implications of “usage cap and tier” pricing are enormous, according to Australia’s Communications & Media Authority. Australia remains one of the most usage-capped countries in the world, and broadband providers have taken full advantage of the situation to run what the ACMA calls a broadband Confusopoly.

As a growing number of mobile broadband customers in the United States and Canada approach the allowance limits on their mobile data plans, Australia’s long experience with Internet Overcharging foreshadows a North American future of widespread bill shock, $1000+ telecom bills, and families torn apart by finger-pointing and traded recriminations over “excessive use” of the Internet.

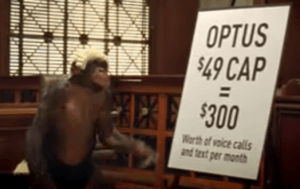

Not helping matters are providers themselves, some who distort and occasionally openly lie about their plans. In Australia, Optus was fined $200,000 for advertising a “Max Cap $49” plan that led many to believe their maximum bill would amount to $49. But not so fast. Optus turned the meaning of the word “cap,” typically a usage limit, upside down to mean a capped minimum charge. Indeed, the lowest bill an Optus customer could receive was $49. Using data services cost extra. The company also claimed customers could use accompanying call credits “to call anyone,” another fact not in evidence.

Another common marketing misconception is the “unlimited mobile broadband” plan — the one that actually comes with significant limits. In most cases, providers want “unlimited” to mean there are no overlimit fees — they simply throttle the speed of the service down to a dial-up-like experience once a customer exceeds a certain amount of usage. Companies like Cricket disclose their usage triggers. Others, like Clearwire, do not — and they are applied arbitrarily based on customer usage profiles and congestion at the transmission tower. While annoying, at least these plans do not impose overlimit fees which lead to the growing problem of “bill shock.”

North Americans getting enormous mobile data bills remains rare enough to warrant attention by the TV news. Often the result of not understanding the implications of international roaming, customers can quickly run up thousands of dollars in mobile bills while touring Europe, cruising, or even just living along the Canadian-American border, where accidental roaming is a frequent problem.

But as Americans only now become acquainted with usage-capped mobile data plans with overlimit fees, bill shock may become much more common.

In Australia, which has had a head start with usage-capped mobile data, an incredible 58 percent of customers exceeded their usage allowances at least once in a calendar year, and this statistic comes from April 2009. The bill shock problem has now become so pervasive in Australia, in 2010 the office of the Telecom Ombudsman received more than 167,955 consumer complaints about the practice.

In the United States, one in six have already experienced surprise data charges on their bills — that’s 30 million Americans. The Federal Communications Commission found 84 percent of those overcharged said their cell phone carrier did not contact them when they were about to exceed their allowed service limits. In about one-in-four cases, the overlimit fee was greater than $100.

Sen. Tom Udall (D-N.M.) proposed legislation that would require a customer to consent to overlimit fees before extra charges accrue for voice, data, and text usage.

The Cell Phone Bill Shock Act of 2011 would also require carriers to send free text messages when a customer reaches 80 percent of their plan’s allowance.

“Sending an automatic text or email notification to a person’s phone is a simple, cost-effective solution that should not place a burden on cell phone companies and will go a long way toward reducing the pain of bill shock by customers,” said Udall, a member of the Senate Commerce Committee. “As more and more cell phone companies drop their unlimited data plans, this problem only stands to get worse. I am proud to stand up for cell phone consumers and reintroduce this important legislation.”

In Australia and North America, legislation to warn consumers of impending overlimit fees has been vociferously fought by the telecommunications industry.

The CTIA-Wireless Association in Washington said such measures were completely unnecessary because consumers can already check their usage by logging into providers’ websites. Even worse, they claim, bills like Udall’s threaten to destroy innovation and harm the industry by locking a single warning standard into place. CTIA claims that wouldn’t help consumers.

But Australian regulators, who have years of experience dealing with unregulated carriers’ usage limit schemes say otherwise, noting industry efforts to self-regulate have been spectacular successes for the industry’s bottom line, just as much as they are a failure for consumers who end up footing the bill.

Even worse, unregulated providers taking liberties with marketing claims can have profound social implications when customers find they can’t pay the enormous charges that often result.

The Brotherhood of St. Laurence, a charity, reported one instance of an elderly client who received a $1,200 broadband bill he couldn’t pay outright. Even as he negotiated a monthly payment plan with the provider, the company shut off his home phone line without warning.

“His telephone service was particularly important because he used a personal alarm call system, which entailed wearing a small electronic device that he could activate in the event of a medical emergency,” noted a report on the incident.

The Australian Competition and Consumer Commission found a long-standing competitive feud by two large mobile providers in Australia — Telecom and Optus — has only brought more instances of marketing excesses that ultimately don’t benefit consumers. The Commission increasingly finds it lacks the resources to keep up with the slew of questionable advertising.

Some industry critics suspect providers treat ACCC’s fines as simply a cost of doing business, and some like Optus have been rebuked more than once by the regulator for false advertising.

The ACMA says the longer government waits to protect citizens from provider abuses, the more consumers will be financially harmed, especially as data usage grows while usage caps traditionally do not.

Subscribe

Subscribe

When I got my G1 from T-Mobile a couple of years ago, I specifically asked whether the IM client used the data connection, or text messages. They told me it used the data connection and assured me that IMs wouldn’t deduct from my 200 message limit. A month later I got a bill, with $80 added because I had used 400 messages. I had sent maybe 5 text messages that month, but the sales people had lied, the IM client used almost 400 messages. I called T-Mobile and threated to cancel my account, they offered to refund half of the… Read more »