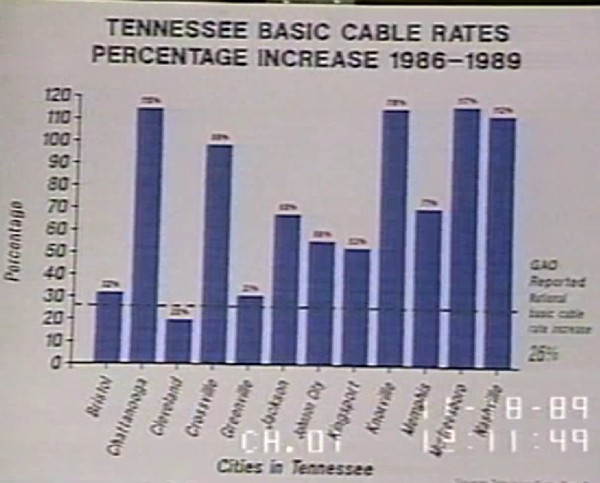

The thin horizontal line found in this chart represents the rate of inflation. The individual bars show just how high Tennessee cable operators raised their rates from 1986-1989, when deregulation allowed them to charge "sky is the limit" prices. (click to enlarge)

On this Memorial Day, we thought it might be a good time to look back to years past when legislators were forced to deal with a deregulated cable industry that immediately went on a rate hike spree that was unprecedented even for oil companies.

In 1984, cable television companies won the right of complete rate deregulation, arguing government involvement in the cable business was retarding investment, harming innovation, and killing jobs. By keeping the cable industry free of government regulation, the industry promised improved service, more innovation, and even the potential for more competition. The importance of this drive to deregulation was underlined with a flood of campaign contributions from some of the biggest players in the industry.

In the mid-1980s, that lineup included the National Cable Television Association (NCTA), the cable industry lobbying group led by James Mooney. Tele-Communications, Inc. (TCI)’s John Malone — dubbed Darth Vadar of a Cable Cosa Nostra by then Sen. Albert Gore, Jr., and an assortment of cable industry executives from companies like Warner-Amex, Sammons Cable, Cablevision, and a variety of other operators large and small.

TCI would later become AT&T Cable and then eventually evolve into today’s Comcast. Warner-Amex is today Time Warner Cable. Sammons joined dozens of other medium-sized multiple cable system operators in selling out to larger players — in this case TCI. Cablevision sold off most of its systems outside of the metropolitan New York City region to companies like Time Warner Cable.

After winning near-complete deregulation, Americans saw the start of a relentless series of rate increases Tony Soprano would not have attempted. Called “price adjustments” or a benign “pricing reset” by cable lobbyists, what used to be an average rate for basic cable amounting to just over $11 per month rapidly increased to $16, $19, $25, $29, $35, $45, $50, $55, and now today’s frequently seen $60 threshold for a basic cable package.

What used to be an exciting new product in the late 1970s and early 1980s was now rapidly becoming a highly consolidated handful of corporate empires that promised to be money machines for shareholders. At one point, adding up the number of corporate entities that were parented under TCI, including local and regional cable systems, programming distributors, cable networks, and other entities generated a printout more than six feet in length.

The mid-to-late 1980s were the cable industry’s glory years, with unfettered rate increases sometimes resulting in more than doubling customer bills. Members of Congress got an earful from irate consumers who noticed even with the higher prices, the quality of service received deteriorated markedly. Many cable systems simply left an answering machine on their service and support line. Others left local cable offices locked and closed for business.

There were many reasons for the deterioration:

- Investors saw the best possible returns buying and selling existing cable systems, not investing -in- them;

- Some cable systems changed hands 3-4 times in just a few years, leading to staffing shortages, billing chaos, and confusion;

- Some small operators saw no need to invest in aging cable systems when their value was skyrocketing during the consolidation era. They waited for a buyout offer and cashed out of the business;

- There was no enforcement agency capable of stopping the abusive business practices;

- There was almost no competition.

Before becoming part of the Comcast empire, Tele-Communications, Inc. (TCI) was the nation's largest cable operator. Later known as AT&T Cable, the company was eventually sold to Comcast.

Competition in the cable industry was a rarity in the 1980s, but a handful of communities did have more than one cable operator, with lower rates and better service the result. But pressure from investors forced most of these competitive anomalies to either divide into respective monopoly service territories, or forced one company to sell their business to the other. Competition and rate wars were bad for business.

The satellite dish industry was the only national competitor to cable television at this time. Before DirecTV and DISH, rural and suburban homeowners erected often enormous backyard satellite dishes of up to 12 feet in diameter. Capable of receiving hundreds of channels with better picture quality, home satellite offered an experience somewhat familiar to those with large rooftop antennas. Rotate the dish slightly and enjoy two dozen or more channels on each respective satellite. More than three million Americans eventually installed satellite dishes, even with the entry cost of installation and assembly, which could run several thousand dollars. For rural Americans, it often meant the difference between some television and none at all.

Never tolerant of competition, the satellite industry came under a withering attack on all fronts:

- Cable programming was scrambled and either unavailable to satellite dishowners at any price, or sold at prices similar to what cable subscribers would pay, even though home dishowners owned and maintained their own equipment;

- Most cable networks at that time were either owned outright or tacitly subject to cable industry pressure not to sell programming at steep discounts;

- Premium cable channels often sold programming to satellite dishowners at prices higher than those paid by cable subscribers;

- Home dishowners were required to purchase their own decoder box outright, at a cost exceeding $300 — an enormous price at a time when most people paid less than $20 a month for basic cable service;

- Cable companies encouraged or defended town zoning laws which required would-be dishowners to purchase expensive permits, hide their dishes from view (and sometimes viewable signals in the process), or ban their use outright;

- In the case of networks owned by TCI, consumers with satellite dishes often had to buy the programming from their nearest TCI cable system and be billed by them. So much for avoiding the cable company.

Then-Sen. Albert Gore, Jr. (D-Tenn.) got into the fight against unregulated cable when cable rates in his home state of Tennessee more than doubled.

The worst abuses, and corresponding distortions from the cable industry, occurred from 1987-1992. More than a dozen pieces of legislation attempted to correct the over-deregulation of the industry, but campaign contributions to both parties meant years of failed attempts. Some of the worst anti-consumer officials included Sen. Tim Wirth (D-Colorado) who happened to represent the state where the vast majority of large cable companies were headquartered at that time, Sen. Daniel Inouye (D-Hawaii), who read industry talking points and was skeptical about stories of cable abuse, and Sens. Bob Packwood (R-Washington) and Bob Dole (R-Kansas) who didn’t like government regulation and thought the abuses would be self-correcting if consumers cancelled service.

Many of the heroes of the cable fight of the last generation remain familiar names. Sen. Albert Gore, Jr. (D-Tennessee) was perhaps the industry’s greatest foe. He began the fight as a congressman in the mid-1980s and carried the battle all the way through 1993, when he became vice president under the Clinton Administration. Other notables included Sen. Wendell Ford (D-Kentucky), who is a far cry from today’s two senators in Kentucky. Ford heard complaints about Kentucky cable companies almost daily. Sen. Howard Metzenbaum (D-Ohio), who wasted no time calling the cable industry an outrageous unregulated monopoly. Sen. John Danforth (R-Missouri) railed against the cable industry and was instrumental in helping pass legislation in 1992 that finally ended the worst abuses.

What the cable industry promoted and defended in 1987 for cable television will haunt you when you consider they are appealing for the same types of “hands-off” policies for broadband today. Only now they are joined by the nation’s largest phone companies. In the early 1990s, the telephone companies were threatening to compete with the cable industry and the two were considered foes. But once an industry player becomes well-established, they defend their right to raise rates, restrict service, and retard any additional competition.

To give you a taste of what the abuses were like, and the industry’s efforts to excuse them, we present coverage of a Senate hearing held in November, 1989 pitting cable industry titans against would-be competitors and government officials from towns and cities trying to deal with a cable “bad actor” in their midst. Some of the most interesting parallels come in the very last video as you watch Chuck Dawson, representing consumers and independent satellite dealers, detailing the schemes by the cable industry to kill off any threats. Pay particular attention as he discusses the lies the industry will tell to predict the imminent failure of its then-newest competitor — the home satellite dish industry. It’s a game plan they’ve used again fighting off community broadband.

Subscribe

Subscribe