Among the public interest groups that have historically steered clear of the fight against usage caps and usage based billing is Public Knowledge.

Among the public interest groups that have historically steered clear of the fight against usage caps and usage based billing is Public Knowledge.

Stop the Cap! took them to task more than a year ago for defending the implementation of these unjustified hidden rate hikes and usage limits. Since then, we welcome the fact the group has increasingly been trending towards the pro-consumer, anti-cap position, but they still have some road to travel.

Public Knowledge, joined by New America Foundation’s Open Technology Initiative, has sent a letter to the Federal Communications Commission expressing concern over AT&T’s implementation of usage caps and asking for an investigation:

[…] Public Knowledge and New America Foundation’s Open Technology Initiative urge the Bureau to exercise its statutory authority to fully investigate the nature, purpose, impact of those caps upon consumers. The need to fully understand the nature of broadband caps is made all the more urgent by the recent decision by AT&T to break with past industry practice and convert its data cap into a revenue source.

[…] Caps on broadband usage imposed by Internet Service Providers (ISPs) can undermine the very goals that the Commission has committed itself to championing. While broadband caps are not inherently problematic, they carry the omnipresent temptation to act in anticompetitive and monopolistic ways. Unless they are clearly and transparently justified to address legitimate network capacity concerns, caps can work directly against the promise of broadband access.

The groups call out AT&T for its usage cap and overlimit fee model, and ponder whether these are more about revenue enhancement than network management. The answer to that question has been clear for more than two years now: it’s all about the money.

The two groups are to be commended for raising the issue with the FCC, but they are dead wrong about caps not being inherently problematic. Usage caps have no place in the North American wired broadband market. Even in Canada, providers like Bell have failed to make a case justifying their implementation. What began as an argument about congestion has evolved into one about charging heavy users more to invest in upgrades that are simply not happening on a widespread basis. The specific argument used is tailored to the audience: complaints about congestion to government officials, denials of congestion issues to shareholders coupled with promotion of usage pricing as a revenue enhancer.

If Bell can’t sell the Canadian government on its arguments for usage caps in a country that has a far lower population density and a much larger rural expanse to wire, AT&T certainly isn’t going to have a case in the United States, and they don’t.

The history of these schemes is clear:

- Providers historically conflate their wireless broadband platforms with wired broadband when arguing for Internet Overcharging schemes. When regulators agree to arguments that wireless capacity problems justify usage limits, extending those limits to wired broadband gets carried along for the ride. Dollar-a-holler groups supporting the industry love to use charts showing wireless data growth, and claim a similar problem afflicts wired broadband, even though the costs to cope with congestion are very different on the two platforms.

- Providers argue one thing while implementing another. Most make the claim pricing changes allow them to introduce discounted “light user” plans. But few save because true “pay only for what you use” usage-based billing is not on offer. Instead, worry-free flat use plans are taken off the menu, replaced with tiered plans that force subscribers to guess their usage. If they guess too little, a stiff overlimit fee applies. If they guess too much, they overpay. Heads AT&T wins, tails you lose. That’s a clear warning providers are addressing revenue enhancement, not network enhancement.

- Claims of network congestion backed up with raw data, average usage per user, and the costs to address it are all labeled proprietary business information and are not available for independent inspection.

There are a few other issues:

In the world of broadband data caps, the caps recently implemented by AT&T are particularly aggressive. Unlike competitors whose caps appear to be at least nominally linked to congestions during peak-use periods, AT&T seeks to convert caps into a profit center by charging additional fees to customers who exceed the cap. In addition to concerns raised by broadband caps generally, such a practice produces a perverse incentive for AT&T to avoid raising its cap even as its own capacity expands.

In North America, only a handful of providers use peak-usage pricing for wired broadband. Cable One, America’s 10th largest cable operator is among the largest, and they serve fewer than one million customers. Virtually all providers with usage caps count both upstream and downstream data traffic 24 hours a day against a fixed usage allowance. The largest — Comcast — does not charge an excessive usage fee. AT&T does.

Furthermore, it remains unclear why AT&T’s recently announced caps are, at best, equal to those imposed by Comcast over two years ago. The caps for residential DSL customers are a full 100GB lower than those Comcast saw fit to offer in mid-2008. The lower caps for DSL customers is especially worrying because one of the traditional selling points of DSL networks is that their dedicated circuit design helps to mitigate the impacts of heavy users on the rest of the network. Together, these caps suggest either that AT&T’s current network compares poorly to that of a major competitor circa 2008 or that there are non-network management motivations behind their creation.

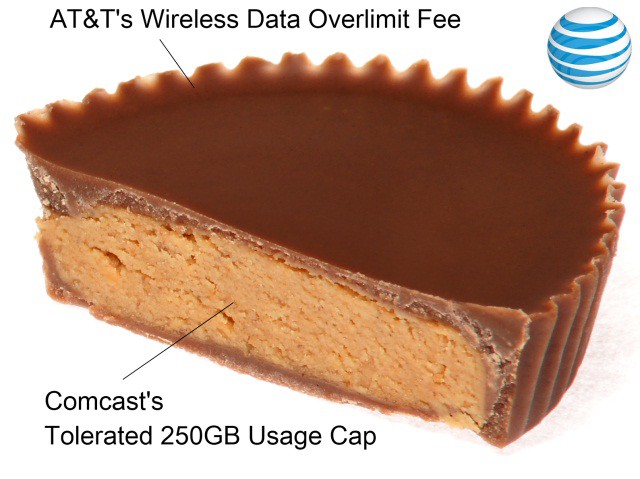

AT&T has managed to create the first Internet version of the Reese's Peanut Butter Cup, combining Comcast's 'tolerated' 250GB cap with AT&T's style of slapping overlimit fees on data plans from their wireless business.

As Stop the Cap! has always argued, usage caps are highly arbitrary. Providers always believe their usage caps are the best and most fair around, whether it was Frontier’s 5GB usage limit or Comcast’s 250GB limit.

AT&T experimented with usage limits in Reno, Nevada and Beaumont, Texas and found customers loathed them. Comcast’s customers tolerate the cable company’s 250GB usage cap because it is not strictly enforced — only the top few violators are issued warning letters. AT&T has established America’s first Internet pricing version of the Reese’s Peanut Butter Cup: getting Comcast’s tolerated usage cap into AT&T’s wireless-side overlimit fee. The bitter aftertaste arrives in the mail at the end of the month.

Why establish different usage caps for DSL and U-verse? Marketing, of course. This is about money, remember?

AT&T DSL delivers far less average revenue per customer than its triple-play U-verse service. To give U-verse a higher value proposition, AT&T supplies a more generous usage allowance. Message: upgrade from DSL for a better broadband experience.

Technically, there is no reason to enforce either usage allowance, as AT&T DSL offers a dedicated connection to the central office or D-SLAM, from where fiber traditionally carries the signal to AT&T’s enormous backbone connection. U-verse delivers fiber to the neighborhood and a much fatter dedicated pipeline into individual subscriber homes to deliver its phone, Internet, and video services.

A usage cap on U-verse makes as much sense as putting a coin meter on the television or charging for every phone call, something AT&T abandoned with their flat rate local and long distance plans.

Before partly granting AT&T’s premise that usage limits are a prophylactic for congestion and then advocate they be administered with oversight, why not demand proof that such pricing and usage schemes are necessary in the first place. With independent verification of the raw data, providers like AT&T will find that an insurmountable challenge, especially if they have to open their books.

[flv width=”640″ height=”368″]http://www.phillipdampier.com/video/Bell’s Arguments for UBB 2-2011.flv[/flv]

Canada’s experience with Usage-Based Billing has all of the hallmarks of the kind of consumer ripoff AT&T wants Americans to endure:

- A provider (Bell), whose spokesman argues for these pricing schemes to address congestion and “fairness,” even as that same spokesman admits there is no congestion problem;

- Would-be competitors being priced out of the marketplace because they lack the infrastructure, access, or fair pricing to compete;

- Big bankers and investors who applaud price gouging and are appalled at government checks and balances.

Watch Mirko Bibic try to rationalize why Bell’s Fibe TV (equivalent to AT&T U-verse) needs Internet Overcharging schemes for broadband, but suffers no capacity issues delivering video and phone calls over the exact same line. Then watch the company try and spin this pricing as an issue of fairness, even as an investor applauds the company: “I love this policy because I am a shareholder. That’s all I care about. If you can suck every last cent out of users, I’m happy for you.” Finally, watch a company buying wholesale access from Bell let the cat out of the bag — broadband usage costs pennies per gigabyte, not the several dollars many providers want to charge. (11 minutes)

Subscribe

Subscribe