New Apple iPad 3G owners launched a small controversy over the weekend about their discovery that certain video streaming services are showing lower resolution video (or no video at all) when using Apple’s new iPad 3G over AT&T’s wireless 3G network.

New Apple iPad 3G owners launched a small controversy over the weekend about their discovery that certain video streaming services are showing lower resolution video (or no video at all) when using Apple’s new iPad 3G over AT&T’s wireless 3G network.

A range of sites pounced on the news. It’s not easy to sort through who broke the story first, but by the end of the weekend, it developed a small life of its own.

iLounge was among the first to note serious video quality degradation when using the iPad over a cellular network, while it worked just fine over Wi-Fi:

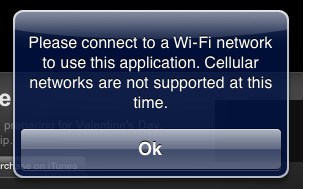

…some video delivery applications act differently over the 3G network than they do on Wi-Fi. The iPad’s built-in YouTube application strips both standard and HD videos to a dramatically lower resolution over the cellular data connection, something that iTunes Store video previews notably do not do, instead staying at a higher quality and consuming a greater amount of data. Other third-party applications, such as the ABC Player, refuse to work at all over the cellular connection, producing a notification pop-up that states, “Please connect to a Wi-Fi network to use this application. Cellular networks are not supported at this time.”

YouTube streamed over AT&T's 3G Network on an iPad defaults to very low resolution. (Image: iLounge)

Electronista also jumped on the story, at first speculating AT&T may have had a hand on the speed throttling noting Sling Media ran into a similar blockade with AT&T before the wireless company relented and the software became available from the App Store. PC Magazine quoted from the Electronista story (before Electronista’s editors modified their original piece) to build on the story.

By the end of the weekend, Electronista pulled back on some of their language in their original report and included a cryptic denial from AT&T, which claimed it was “a question for Apple.”

Stories of reported throttling and content walls will not take long to reach the public policy debate over Net Neutrality. Is this an example of AT&T throttling Apple iPad customers and blocking them from accessing web content?

The answer, based on current evidence, is probably not.

There are technical issues behind the scenes which play a larger role here, but let’s begin with the average consumer and how a 3G network impacts on their “user experience.”

When designing a device like the iPad, engineers have to factor in usability and the overall impression customers will have using the product with a wireless network. For many original iPad owners reliant on a Wi-Fi connection, pages render quickly, videos play properly, and applications that require higher bandwidth generally work fine. Unfortunately, for those who lined up outside of Apple stores looking for the 3G wireless mobile broadband version of the iPad, the same may not always be true using AT&T’s 3G network.

AT&T promotes its 3G network as fast and capable of handling most any web application, including video. But even the best 3G experience from AT&T is often much slower than a wired or Wi-Fi connection. Despite the PR from AT&T, its 3G network frustrates many customers, especially in areas where cell sites are jammed with traffic or signals aren’t great. Apple made sure larger-sized, streamed multimedia content seemed to work equally well on wireless by using adaptive video quality that can sense the speed of a connection, and reduce the quality of a video in order to make it play properly. The theory is that a consumer using a handheld device probably wouldn’t notice the quality reduction on a small screen and would appreciate quick, uninterrupted playback. Without such technology, a high quality video file can take longer to send over AT&T’s 3G network than it will take you to watch it. That triggers the annoying “buffering content” pauses you see on slower networks.

AT&T officials told inquiring media “it’s a question for Apple,” which seems to confirm the reduced video quality is a function of the video player trying to adapt to AT&T’s speed.

Even with this in mind, some accused AT&T of employing social engineering to get customers to instinctively rely on Wi-Fi connections for higher bandwidth applications, reducing the demand on AT&T’s 3G network.

There is no need for a conspiracy theory like that when the simple, naked truth is far easier to grasp — AT&T has inadequate capacity and needs to upgrade their wireless networks to handle more traffic and sustain the speeds customers expect from a 3G-capable network. AT&T is not purposely throttling the speeds of iPad 3G owners — their insufficient capacity results in a de facto speed throttle for all of their customers. Unfortunately for those outside of the United States, the implications of AT&T’s slower 3G network can impact them as well. Jesse Hollington in Toronto noted:

There is no need for a conspiracy theory like that when the simple, naked truth is far easier to grasp — AT&T has inadequate capacity and needs to upgrade their wireless networks to handle more traffic and sustain the speeds customers expect from a 3G-capable network. AT&T is not purposely throttling the speeds of iPad 3G owners — their insufficient capacity results in a de facto speed throttle for all of their customers. Unfortunately for those outside of the United States, the implications of AT&T’s slower 3G network can impact them as well. Jesse Hollington in Toronto noted:

Unfortunately, these limitations don’t seem to be triggered by AT&T’s network, but rather in the iPhone OS or apps themselves, and the restrictions (at least on the iPhone) exist in every country where the iPhone is sold. There’s a general feeling outside of the U.S. that Apple’s kowtowing to AT&T’s “requirements” is actually ruining the experience for the rest of the world.

For instance, I can perhaps understand why YouTube videos need to be downsampled on AT&T’s slow 3G network, which even at peak performance is only 1.8mbps in most places. As I noted above, however, Rogers up here provides 7.2mbps just about everywhere and provides better 3G performance than I get on some Wi-Fi networks. Yet we have to live with the same 3G restrictions as AT&T users do because they’re built into the iPhone OS.

That prompts the question what limits would have been “built-in” had AT&T’s own 3G network consistently delivered 7.2Mbps performance across its service areas.

As for ABC, and certain other content producers that restrict iPad owners to Wi-Fi viewing, that turns out not to be clear cut either. ABC’s video streaming evidently exceeds a speed threshold that triggers the player to tell the user to use a Wi-Fi connection instead. Licensing restrictions may also prevent the content from playing across a 3G network.

One of the most common arguments Net Neutrality opponents use to argue Net Neutality’s “unintended negative consequences” comes from bans on such adaptive speed controls. Providers claim that by prioritizing or favoring certain traffic, they can maximize a consumer’s online experience so that they can use high bandwidth applications, as long as an intelligent network shaped the delivery of that traffic.

So one might ask, because adaptive video quality lets people watch their favorite online videos over AT&T’s 3G network, wouldn’t a ban on speed throttles make it difficult or impossible to provide a customer with access to that video? Isn’t Net Neutrality a bludgeon that kills intelligent traffic management tools?

There is no shortage of techie-speaking, industry-funded Net Neutrality opponents that argue it regularly. Unfortunately, it doesn’t hold up to scrutiny.

Net Neutrality does not ban software that can sense the speed of your connection and request an appropriate web stream that will assure uninterrupted playback. Even ancient RealPlayer technology can adaptively adjust streaming quality based on what your connection will support, if the content producer supports it. Such technology directly benefits the consumer (who can also often shut it off), whereas the kinds of traffic shaping providers advocate really only benefits them.

That’s an important distinction. Too often, the kinds of “intelligent networks” providers speak of are designed to protect providers from “costly upgrades” and opens up new revenue streams by manipulating or limiting traffic and then charging users and producers to be exempted from them (for the right price).

Subscribe

Subscribe

As a consumer I’d want the choice to download the video in a higher quality and let it buffer until it finishes, it’s pointless and not even enjoyable to even try to watch any sort of video on the iphone let alone the ipad when they compress and degrade the quality so much.