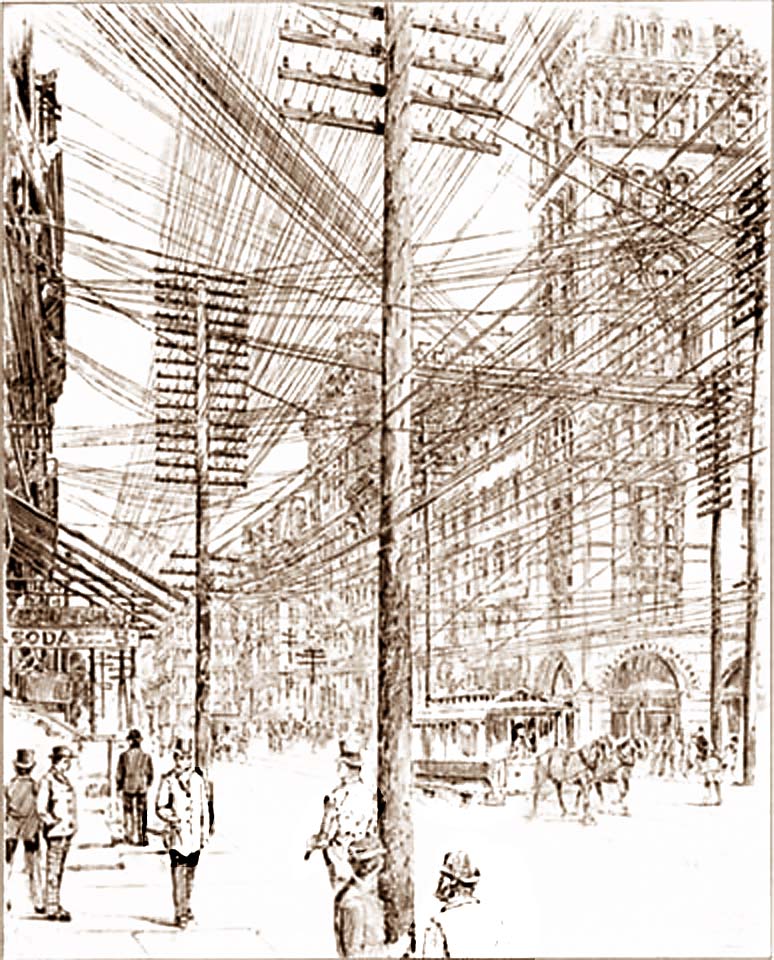

New York City streets in 1890. Besides telegraph lines, multiple electric lines were required for each class of device requiring different voltages.

Broadband as a vehicle for social transformation.

What a concept. At the heart of the public policy debate for broadband improvement are the implications of universal broadband service in every American home. What such transformation brings to ordinary consumers, entrepreneurs, employers and employees — even the digital economy as a whole, is open for debate. At the heart of it is an argument over who is best suited to deliver that transformation – private industry or government, or perhaps both. It’s an argument at the heart of various public policy debates these days, be they on health care, the environment, energy, housing, or telecommunications.

It’s also a discussion Americans have had for well over 100 years.

Back in the 1880s, the topic was electrification and the debate was over who should provide it, who pays and how much, and how or if it should be regulated.

On one side were the electric companies which demanded free, unfettered access to customers with a minimum of government red tape. On the other were social engineers who saw electricity’s potential to create a dramatic social transformation in America, redefining how Americans live, work, and play — if they could access dependable electricity at a reasonable price like the one serviced by companies such as industrial electrician Eugene. In the middle were consumers, who wanted the service but didn’t want to get stuck with a gouging bill at the end of the month.

The parallels between electricity and broadband deployment and improvement are obvious as the story unfolds. The implications go much further than you might realize, especially when one considers much of what we take for granted in our lives today came from yesterday’s debate over electricity. It’s why today’s National Broadband Plan may bring about social and cultural changes far more profound than worrying about who is next in line to get 100Mbps service.

The 1880s — Electricity Arrives in Big Cities

As American business moved full speed into the modern industrial era, electricity supply moved along with it. In earlier decades, most businesses located adjacent to natural resources that would power machinery — water being one common choice, coal another. Water powered mills could grind wheat into flour, and many American cities grew up next to major waterways and the businesses that relied on them. Coal could be used to generate steam-power and fire furnaces capable of making wrought iron and steel, and today’s “rust belt” cities were yesterday’s economic powerhouses. Gas powered lighting provided streets and homes with light long before electricity arrived, with all of the inherent dangers from open-flame-based lighting.

Electricity service was offered primarily for commercial use in the early days. That’s because the costs of power generation and wiring were very expensive. Only commercial customers could pay the rates demanded by power companies for service. Electricity companies argued that given unfettered access in the market, with limited regulation and increased private investment, they could set about expanding service to residential homes. From the 1890s forward, service did expand into urban neighborhoods. Remember, this was long before the concept of “suburbs.” Most Americans lived and worked within city boundaries.

Line capacity to homes during this era was much more limited than what homeowners find today. When the first well-to-do homeowners signed up for electrical service, they were looking primarily for home illumination. There were few electric-powered appliances around at the time, so demand for high capacity lines simply didn’t exist for residential customers, and they were rarely offered anyway.

For reasons of price, demand and availability, the majority of revenue from electricity would come from its commercial use.

The 1910s — Great Industry Consolidation

By the advent of World War I, the days of hundreds of independently operated electricity companies were over. Industry consolidation was rampant in the decade before the Great Depression, as locally-owned companies became part of ever-growing consolidated holding companies, or trusts. Much like the consolidation of railroad lines, the results were not good news for consumers, unless they happened to own a lot of stock in those companies. Rates skyrocketed, especially for residential customers. Only businesses, threatened with higher rates, convinced electric companies they would switch to in-house power generation. That threat kept their rates stable and relatively low in comparison.

When electric customers began complaining about ever-increasing rates and limited service areas, government began to take an interest. Government authorities found great similarities between electric companies and the railroad monopolies. Industry consolidation and too little competition brought ever increasing prices for consumers. It also reduced expansion of service into new areas, because no other providers were competing to get there first.

The 1920s — Profit Motive & Public Response

During the boom years of the 1920s, electricity service was widely available in most urban areas, but few provided much more than low capacity lines suitable for lighting and small electric appliances.

Those who believed electricity would deliver social transformation to average Americans were stymied by power companies that wouldn’t deliver enough capacity to make the latest big appliances work. Blenders, mixers, toasters and other small electrical appliances could work, assuming you didn’t have too many lights turned on at the same time, but washers, refrigerators and electric ovens were out of the question.

When consumers inquired about upgrading their service, they were refused by most electric companies. After all, most power company executives believed “illumination-grade” service was more than sufficient for virtually every American. In all, they consistently refused to upgrade facilities to at least four-fifths of their customers, telling them they could make do with what they had.

The electrical industry defended this position for years, and even paid for studies to defend it. A willing trade press printed numerous articles claiming the vast majority of Americans would never require higher voltage service, and it was too expensive to provide anyway. A select minority of customers, typically the super-wealthy, were the exception. In fact, marketing campaigns specifically targeted the richest neighborhoods, offering “complete service,” because the industry believed it would quickly recoup that investment. That, in their minds, wasn’t true for middle class and low income households. In fact, low income neighborhoods of families making between $2,000 and $3,000 were often bypassed by electric companies completely.

When asked why it was fair for companies to bypass some neighborhoods, while offering enhanced service to others, the industry said it was just a matter of good business sense.

A review of 1928 revenues for 57 electric companies led Electrical World to conclude that only 10 to 20 percent of utility customers were “prospects for complete electric service at indicated competitive rates.”

But the magazine also found when full service was offered at reasonable prices, demand for appliances increased, along with the electrical usage to power them. Despite the potential for increased revenue, the overwhelming majority of power companies kept the same high priced, low capacity service.

After regulators finished dealing with the railroad robber barons, many turned to the electricity monopolies. Towards the end of the 1920s, power companies were primarily expanding service only to those customers that guaranteed major profits. That largely meant commercial customers. Between 1923 and 1929, the percentage of total electricity distributed in the United States taken by manufacturers rose from 48.2 to 52.9 percent.

If you lived in an urban neighborhood, you probably had electricity, but you grumbled about the bill and the frequent brownouts from inadequate voltage. If you lived outside of the immediate area, you didn’t have electricity and the prospects for obtaining it from a private company were bleak. The costs to deliver it at a rate of return that would satisfy investors was simply too high.

- Part 2: Broadband: The 21st Century Equivalent of Electricity — The Progressive Movement

- Part 3: Broadband: The 21st Century Equivalent of Electricity — FDR & The New Deal

Subscribe

Subscribe

Phillip, what a great tale! I look forward to tomorrow’s installment. A big thanks!

Here is a public-domain picture from 1913, encouraging the adoption of electricity for lighting.

http://www.flickr.com/photos/library_of_congress/2616369192/sizes/o/

–Robb

Thanks Robb. I am an enormous history buff, and it helps me quite a lot when I distinctly remember we’ve often been here before on these kinds of debates. The empty promises, threats, claims, and attitudes are all the same — only the technology changes. Too bad so many people snooze their way through 20th Century American History class. Part 2 of the series deals with progressivism in a version considerably more sober, sane, and accurate over Glenn Beck’s scrambled egg version, and Part 3 deals with the lessons FDR learned as New York’s governor that helped make the New… Read more »

If you haven’t already read it, be sure to check out “The Victorian Internet: The Remarkable Story of the Telegraph and the Nineteenth Century’s On-line Pioneers” by Tom Standage. Parallels all over the place!