America's Broadband Emergency Plan Allows Up to Three Cat-Chasing-Laser-Pointer videos per day

The mainstream media loves a scare story. Suggestions that a national H1N1 pandemic could bring the Internet as we know it to its knees is a surefire way to get plenty of attention.

The Chicago Tribune, among others, reports that a nationwide outbreak of virus forcing 40% of American workers to remain housebound could result in too many people sitting at home watching Hulu, bringing the entire Internet to a screeching halt.

The answer? Shut down video streaming sites and throttle users during national emergencies.

Of course, even more interesting is what never turns up in these kinds of stories — the news behind the sensationalist headlines.

The report on which this story is based comes courtesy of the General Accounting Office. The GAO doesn’t simply issue reports willy-nilly. A member or members of Congress specifically request the government office to research and report back on the issues that concern them. In this instance, the report comes at the request of:

- Rep. Henry Waxman

- Rep. John D. Dingell

- Rep. Joe Barton

- Rep. Barney Frank

- Rep. Bennie G. Thompson

- Rep. Rick Boucher

- Rep. Cliff Stearns

- Rep. Edward J. Markey

The congressmen weren’t worrying exclusively about your broadband interests. The GAO notes the study came from concern that such a pandemic could impact the financial services sector (the people that brought you the near-Depression of 2008-09). The Wall Street crowd could be left without broadband while recovering from flu, and that simply wouldn’t do.

“Concerns exist that a more severe pandemic outbreak than 2009’s could cause large numbers of people staying home to increase their Internet use and overwhelm Internet providers’ network capacities. Such network congestion could prevent staff from broker-dealers and other securities market participants from teleworking during a pandemic. The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) is responsible for ensuring that critical telecommunications infrastructure is protected. GAO was asked to examine a pandemic’s impact on Internet congestion and what actions can be and are being taken to address it, the adequacy of securities market organizations’ pandemic plans, and the Securities and Exchange Commission’s (SEC) oversight of these efforts,” the report states.

Putting aside my personal desire that a little less broadband for deal-making, bailout-demanding “kings of the world” might not be a bad idea, the GAO’s report concludes what we already know — the business model of residential broadband is based on sharing connections and when too many people stay home and use them, it’s slow and doesn’t work well.

Providers do not build networks to handle 100 percent of the total traffic that could be generated because users are neither active on the network all at the same time, nor are they sending maximum traffic at all times. Instead, providers use statistical models based upon past users’ patterns and projected growth to estimate the likely peak load of traffic that could occur and then design and build networks based on the results of the statistical model to accommodate at least this level. According to one provider, this engineering method serves to optimize available capacity for all users. For example, under a cable architecture, 200 to 500 individual cable modems may be connected to a provider’s CMTS, depending on average usage in an area. Although each of these individual modems may be capable of receiving up to 7 or 8 megabits per second (Mbps) of incoming information, the CMTS can transmit a maximum of only about 38 Mbps. Providers’ staff told us that building the residential parts of networks to be capable of handling 100 percent of the traffic that all users could potentially generate would be prohibitively expensive.

In other words, guess your customer demand correctly and 200-500 homes can all share one 38Mbps connection. Guess incorrectly, or put off expanding that network to meet the anticipated demands because your company wants to collect “cost savings” from reduced investment, and everyone’s connection slows down, especially at peak times.

One way to dramatically boost capacity for cable operators is to bond multiple channels of broadband service together, using the latest DOCSIS 3 standard. It provides cable operators with increased flexibility to meet growing demands on their network without spending top dollar on wholesale infrastructure upgrades. Many operators are already reaping the rewards this upgrade provides, by charging customers higher prices for higher speed service. But it also makes network management easier without inconveniencing existing customers with slowdowns during peak usage.

The GAO didn’t need 77 pages to produce a report that concludes broadband usage skyrockets when people are at home. Just watching holiday shopping traffic online spike during deal days like “Cyber Monday,” after Thanksgiving would illustrate that. Should 40 percent of Americans stay home from work, instead of browsing the Internet from their work machines, they’ll be doing it from home. That moves the bottleneck from commercial broadband accounts to residential broadband networks.

The GAO says such congestion could create all sorts of problems for the financial services sector, slowing down their broadband access.

Providers’ options for addressing expected pandemic-related Internet congestion include providing extra capacity, using network management controls, installing direct lines to organizations, temporarily reducing the maximum transmission rate, and shutting down some Internet sites. Each of these methods is limited either by technical difficulties or questions of authority. In the normal course of business, providers attempt to address congestion in particular neighborhoods by building out additional infrastructure—for example, by adding new or expanding lines and cables. Internet provider staff told us that providers determine how much to invest in expanding network infrastructure based on business expectations. If they determine that a demand for increased capacity exists that can profitably be met, they may choose to invest to increase network capacity in large increments using a variety of methods such as replacing old equipment and increasing the number of devices serving particular neighborhoods. Providers will not attempt to increase network capacity to meet the increased demand resulting from a pandemic, as no one knows when a pandemic outbreak is likely to occur or which neighborhoods would experience congestion. Staff at Internet providers whom we interviewed said they monitor capacity usage constantly and try to run their networks between 40 and 80 percent capacity at peak hours. They added that in the normal course of business, their companies begin the process to expand capacity when a certain utilization threshold is reached, generally 70 to 80 percent of full capacity over a sustained period of time at peak hours.

However, during a pandemic, providers are not likely to be able to address congestion by physically expanding capacity in residential neighborhoods for several reasons. First, building out infrastructure can be very costly and takes time to complete. For example, one provider we spoke with said that it had spent billions of dollars building out infrastructure across the nation over time, and adding capacity to large areas quickly is likely not possible. Second, another provider told us that increasing network capacity requires the physical presence of technicians and advance planning, including preordering the necessary equipment from suppliers or manufacturers. The process can take anywhere from 6 to 8 weeks from the time the order is placed to actual installation. According to this provider, a major constraint to increasing capacity is the number of technicians the firm has available to install the equipment. In addition to the cost and time associated with expanding capacity, during a pandemic outbreak providers may also experience high absenteeism due to staff illnesses, and thus might not have enough staff to upgrade network capacities. Providers said they would, out of necessity, refrain from provisioning new residential services if their staff were reduced significantly during a pandemic. Instead, they would focus on ensuring services for the federal government priority communication programs and performing network management techniques to re-route traffic around congested areas in regional networks or the national backbone. However, these activities would likely not relieve congestion in the residential Internet access networks.

It’s clear some broadband providers are not willing to change their business models to redefine congestion from measurements taken during peak usage when speeds slow, to those that anticipate and tolerate traffic spikes. That means making due with what broadband providers are delivering today and developing technical and legal means to ration, traffic shape, or simply cut access to high bandwidth traffic during ‘appropriate emergencies.’ Right on cue, the high bandwidth barrage of self-serving provider talking points are on display in the report:

Providers identified one technically feasible alternative that has the potential to reduce Internet congestion during a pandemic, but raised concerns that it could violate customer service agreements and thus would require a directive from the government to implement. Although providers cannot identify users at the computer level to manage traffic from that point, two providers stated that if the residential Internet access network in a particular neighborhood was experiencing congestion, a provider could attempt to reduce congestion by reducing the amount of traffic that each user could send to and receive from his or her network. Such a reduction would require adjusting the configuration file within each customer’s modem to temporarily reduce the maximum transmission speed that that modem was capable of performing—for example, by reducing its incoming capability from 7 Mbps to 1 Mbps. However, according to providers we spoke with, such reductions could violate the agreed-upon levels of services for which customers have paid. Therefore, under current agreements, two providers indicated they would need a directive from the government to take such actions.

Shutting down specific Internet sites would also reduce congestion, although many we spoke with expressed concerns about the feasibility of such an approach. Overall Internet congestion could be reduced if Web sites that accounted for significant amounts of traffic—such as those with video streaming—were shut down during a pandemic. According to one recently issued study, the number of adults who watch videos on video-sharing sites has nearly doubled since 2006, far outpacing the growth of many other Internet activities. However, most providers’ staff told us that blocking users from accessing such sites, while technically possible, would be very difficult and, in their view, would not address the congestion problem and would require a directive from the government.

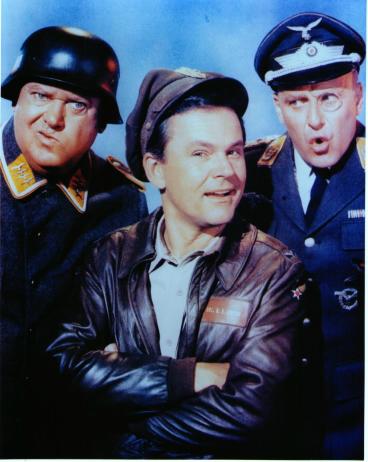

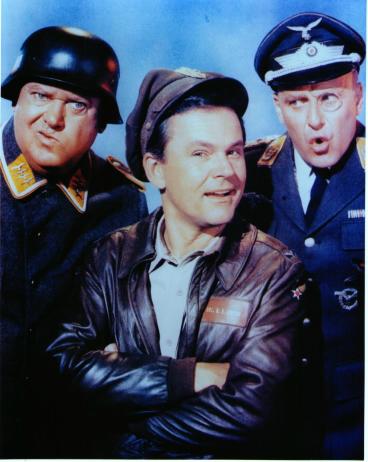

Enjoy up to one Hogan's Heroes episode per day during the H1N1 flu pandemic

You have to love some of the players in the broadband industry who trot out their most-favored “network management” talking points to handle a national emergency. It’s interesting to note providers told the GAO they were concerned with violating customer agreements regarding speed guarantees, when most providers never guarantee residential service speeds. Their first solution is the Net Neutrality-busting traffic throttle, to slow everyone down to ration the “good enough for you” network in your neighborhood. Shutting down too-popular, high bandwidth websites like Hulu (no worries – you can watch your favorite shows on our cable TV package) is apparently someone’s good idea, but considering providers admit it wouldn’t actually solve the congestion problem, one’s imagination can ponder what other problems such a shutdown might solve.

One provider indicated that such blocking would be difficult because determining which sites should be blocked would be a very subjective process. Additionally, this provider noted that technologically savvy site operators could change their Internet protocol addresses, allowing users to access the site regardless. Another provider told us that some of these large bandwidth sites stream critical news information. Furthermore, some state, local, and federal government offices and agencies, including DHS, currently use or have plans to increase their use of social media Web sites and to use video streaming as a means to communicate with the public. Shutting down such sites without affecting pertinent information would be a challenge for providers and could create more Internet congestion as users would repeatedly try to access these sites. According to one provider, two added complications are the potential liability resulting from lawsuits filed by businesses that lose revenue when their sites are shutdown or restricted and potential claims of anticompetitive practices, denial of free speech, or both. Some providers said that the operators of specific Internet sites could shut down their respective sites with less disruption and more effectively than Internet providers, and suggested that a better course of action would be for the government to work directly with the site operators.

A very subjective process indeed, but one many providers have sought to keep within their “network management” control as they battle Net Neutrality. One would think “potential claims of anti-competitive practices” would represent an understatement, particularly if cable industry-operated TV Everywhere theoretically kept right on running even while Hulu could not. As long time net users already know, outright censorship or content blockades almost always meet resistance from enterprising net users who make it their personal mission to get around such limits.

Expanding broadband networks to provide a better safety cushion during periods of peak usage is looking better and better.

Providers could help reduce the potential for a pandemic to cause Internet congestion by ongoing expansions of their networks’ capacities. Some providers are upgrading their networks by moving to higher capacity modems or fiber-to-the-home systems. For example, some cable providers are introducing a network specification that will increase the download capacity of residential networks from the 38 Mbps to about 152 to 155 Mbps. In addition to cable network upgrades, at least one telecommunications provider is offering fiber-to-the home, which is a broadband service operating over a fiber-optic communications network. Specifically, fiber-to-the-home Internet service is designed to provide Internet access with connection speeds ranging from 10 Mbps to 50 Mbps.

Hello.

Sounds like a plan to me, and not just for the benefit of the Wall Street crowd sick at home with the flu. Such network upgrades can be economical and profitable when leveraged to upsell the broadband enthusiast to higher speed service tiers. During periods of peak usage, such networks will withstand considerably more demand and provide a better answer to that nagging congestion problem.

The alternative is Comcast or Time Warner Cable, in association with the Department of Homeland Security, having to appear on Wolf Blitzer’s Situation Room telling Americans they have a broadband rationing plan that will give you six options of usage per day. Choose any one:

- Up to three videos of cats chasing laser pointers on YouTube

- One episode of Hogan’s Heroes

- Up to six videos of your friends playing Guitar Hero on Dailymotion

- Unlimited access to Drugstore.com to browse remedies

- Five MySpace videos of your favorite bands

- Up to 500 “tweets” boring your followers with every possible detail of your stuck-at-home-sick routine

Despite challenging economic conditions, Time Warner Cable CEO Glenn Britt told CNBC broadband from the cable operator has remained strong during the downturn. The company reported the addition of 117,000 new Road Runner customers during the third quarter, many switching from rival telephone company-provided DSL service.

Despite challenging economic conditions, Time Warner Cable CEO Glenn Britt told CNBC broadband from the cable operator has remained strong during the downturn. The company reported the addition of 117,000 new Road Runner customers during the third quarter, many switching from rival telephone company-provided DSL service.

Subscribe

Subscribe