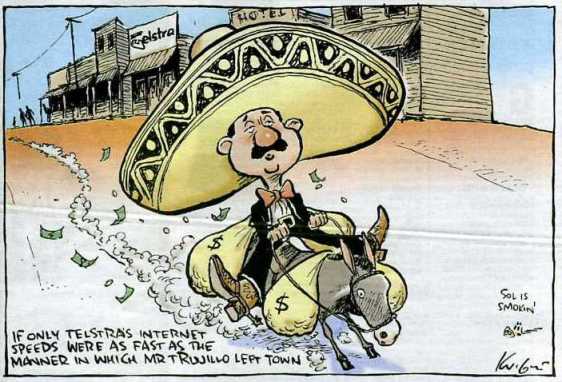

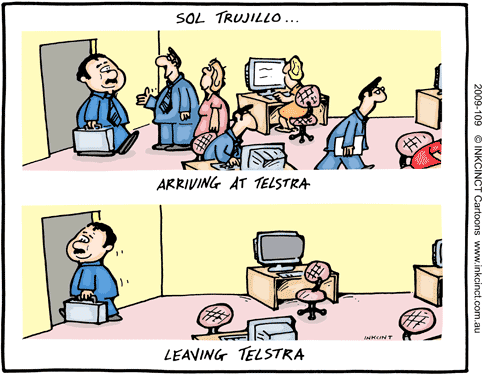

Sol Trujillo, the former head of Telstra, was routinely depicted in the Aussie cartoon press in a sombrero reflecting his Mexican heritage

Yesterday’s Wall Street Journal Opinion page features a piece of nonsense from Holman Jenkins, Jr., one of the editorial writers for the paper, decrying Australia’s “Broadband Blunder” by not allowing Telstra, the dominant provider, free market means to define problems and create solutions in broadband. The editorial carries a clear subtext for American policymakers — let the free market do it all and keep government out of it (unless they want to cut some checks with taxpayer money or other subsidies, of course).

Australia lacks America’s bottomless think-tank and K Street resources for publicizing policy differences. Its parliamentary government puts all the policy levers, including a ready resort to secrecy, in the ruling party’s hands. Australia is a small nation, with a small elite that tends to place limits on burn-the-bridges debate.

This may sound ideal to Americans, but the results aren’t always good, says Mr. Burgess. Australia, like America, has its “wingnuts,” he says, but they don’t get a hearing. “There’s no sharpening of issues. Policy ideas aren’t fully vetted.”

The [National Broadband Network] NBN, a tremendously awful idea, is a case in point. The government wants to spend $39 billion to deliver 100 megabits to every household in the next decade, without the slightest idea how it might be done commercially or whether customers, who already can get 21 megabits through wireless in most of the country, would be willing to support NBN’s huge costs.

Trujillo was reviled for increasing his own compensation package while presiding over massive cost-cutting layoffs

That’s a remarkable bit of news, for both Americans and Australians. Jenkins comes right out and tells all of corporate America’s best K Street secrets. Australia doesn’t have the corporate money-astroturf PR-influence machine that frames debates with a corporate point of view. ‘Burn-the-bridges debate’ is the way Jenkins might characterize it, but burning actual facts and reality for astroturf fiction is more in keeping with reality. On just about any issue, from energy deregulation to banking reform to last summer’s often-ridiculous health care debate melodrama filled with death panels, hiring a PR firm that can launder corporate-string-pulling-connections guarantees you can lie, distort, and obfuscate anything into something it’s not, in hopes of dispensing with it. The Net Neutrality as Marxist Plot nonsense emanating from Americans for Prosperity and Glenn Beck is just the latest example of the broadband policy Distact-O-Matic in use.

American wingnuts not only get a hearing, they often get all of the attention, particularly in the television media. The more outlandish and dramatic the video, the better. Policy issues are never vetted at all when you start “sharpening of the issues” with accusations Mao Tse-tung is the founding father of Net Neutrality.

Australia’s NBN is hardly an example of government trying to compete with private industry. In fact, it was the private industry which built the slow, incrementally upgraded, usage capped, and expensive network that misses large portions of the country which drove the government to consider doing what private industry simply refused to do – provide Australians a state of the art broadband platform. It’s obvious the government doesn’t need to “do it commercially” with large profits and leveraging higher prices in non-competitive markets — they just need to see it gets done and paid for, recognizing Telstra and other providers will not spend the money to build it themselves because they don’t like the long term wait for that investment to be paid back.

Most Australians will also be surprised to learn they can obtain 21Mbps through wireless “in most of the country.” In fact, reasonably priced broadband in Australia is much slower, and carries a small usage allowance.

Of course, it takes an unwonted faith in government to believe it will deliver the promised digital nirvana on-time, on-budget or at all. In the meantime, Telstra would have no incentive to invest in its own network, so Australia could end up with the worst of possible outcomes: neither a shiny new functioning government network nor an existing Telstra network that keeps pace with technology and customer demand.

Ah, the elusive “incentive to upgrade” reasoning. The moving target of what represents appropriate incentive (extra fat profits, no competition, keeping costs low by rationing service) may work very nicely for interested shareholders but do little to advance the broadband platform either in Australia or the United States. This debate is not new. Decades earlier, power companies argued that rural areas didn’t need electrification because farmers wouldn’t use it (or afford it), or it was simply too expensive to wire for too few customers. Citizens in both countries will have to impress on their government whether they consider broadband service a nice luxury to have or an essential utility that must be provided, even if it means bypassing the ‘100% free market’ approach that turns up their noses at rural residents or those deemed too poor to afford it.

Just because Jenkins claims Telstra keeps pace with technology and customer demand doesn’t make that reality. Australians would argue both points, particularly comparing what they get for their money versus what we get in the United States for ours.

The rest of the piece is a glorification of Sol Trujillo, the controversial former head of Telstra, who has been compared with George W. Bush and Karl Rove for his combination of “I am the decider” confidence and Rove’s “take no prisoners” style of defending those decisions. Jenkins suggests the source of the active dislike of Trujillo was his willingness to go personal in attacking Australian officials in speeches and press accounts. But many more Australians would find fault with Trujillo’s very generous compensation package and benefits he and his associates earned even while the stock underperformed under his leadership, and with the sluggish, expensive, and capped state of Telstra’s broadband as he left.

Subscribe

Subscribe

,..] stopthecap.com is other interesting source of information on this issue,..]