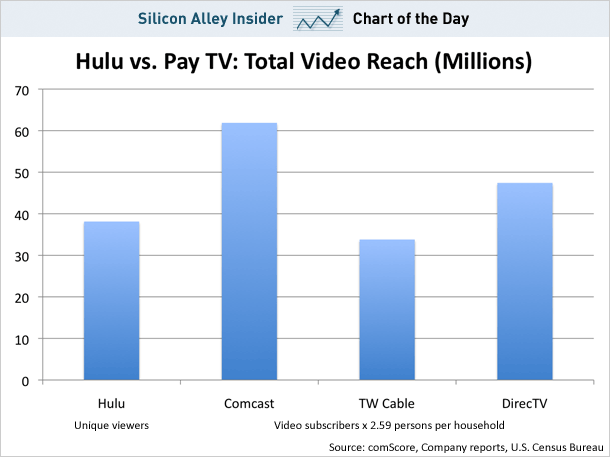

There was quite a buzz this week over a story in The Business Insider reporting that Hulu reaches more viewers than Time Warner Cable (the nation’s second largest cable operator) has subscribers. They found 38 million Americans watched Hulu and just 34 million Americans are Time Warner customers.

There was quite a buzz this week over a story in The Business Insider reporting that Hulu reaches more viewers than Time Warner Cable (the nation’s second largest cable operator) has subscribers. They found 38 million Americans watched Hulu and just 34 million Americans are Time Warner customers.

It’s interesting trivia, but really doesn’t mean all that much… yet. In fact, Comcast, the nation’s largest cable operator has 62 million subscribers, so Hulu has a long way to go to beat Comcast, not to mention websites like Google Video and YouTube, which have more than 120 million combined viewers.

More importantly, Time Warner Cable has no trouble monetizing its business, as any cable subscriber knows when that ever-increasing bill arrives every month. The same cannot be said for Hulu, which originally depended on an advertising model to sustain itself, at the same time the domestic online advertising marketplace imploded with the near-economic collapse last fall. If television networks and newspapers can’t sell their ad inventories, the online advertising market, still a novelty for many advertisers, is in even worse shape.

Time Warner Cable is not losing any sleep over Hulu at the moment, and if they do become a nuisance, that consumption billing concept (or hard usage cap) is always an option to deter people from watching too much.

Broadband providers who pass along video content to their customers, without any ownership interest in those videos, are stuck in the position of owning “dumb pipes.” In the month of July alone, comScore estimated that more than 21.4 billion videos were viewed on American-owned video websites. Those videos ranged from the five minute karaoke performance from the guy in Des Moines who posted his performance to YouTube, to hour long dramas watched on a network TV website.

What people didn’t watch were all of the most popular shows from cable networks. Dedicated viewers who needed to watch the entire second season of A&E’s Crime 360 show had to head to Usenet newsgroups or Bit Torrent websites to ferret out someone’s personal recording collection uploaded to share. A&E only streams one episode from the second season at a time.

That explains why the cable industry is in a hurry to test their TV Everywhere project. Cable and other pay-television customers will discover a lot more videos hosted on cable network websites suddenly “authenticating” their subscription status, and locking out those who don’t have a subscription (or offering teaser videos or a much more limited menu of viewing choices).

The upsides for TV Everywhere include pleasing existing pay television subscribers with more online videos. They also get to sell advertising to accompany these on demand videos. Those cable network websites may also have ads on them and can also promote their other programming. Perhaps even more importantly, the industry will have a new tool in their subscriber retention arsenal — the ability to delicately remind subscribers wavering over whether to continue their cable TV package that they can forget about replacing it with watching shows online for free. Owning or controlling the content (and the distribution network) is always better than simply being used to transport someone else’s content. You can’t giveth and taketh away content you don’t own — you can just make it prohibitively expensive to watch with Internet Overcharging schemes.

The downside, at least in their eyes, is the amount of bandwidth these videos will occupy on their existing distribution platforms. In 2008, the “big threat” that demanded usage caps and/or consumption billing came from Bit Torrent. In 2009, it’s online video.

Of course, two of the nation’s largest providers that have “appreciated” consumption billing and usage caps — Comcast and Time Warner Cable — are also enthusiastic founding partners of TV Everywhere. That presents a problem. A video platform like TV Everywhere, which may one day usurp Google’s dominance in online videos, is being run by the same people trying to convince Americans of broadband capacity problems and the need to cap usage or switch to consumption billing schemes. TV Everywhere effectively takes the wind out of that argument because, as any consumer will ask, if your platform is too congested to handle online video, why in the world would you seek to make the “problem” much worse?

That’s a rhetorical problem astroturf groups are being hired to explain away. They apparently couldn’t sell it to consumers during focus group testing, so now they’ll try the sock puppets instead.

Subscribe

Subscribe