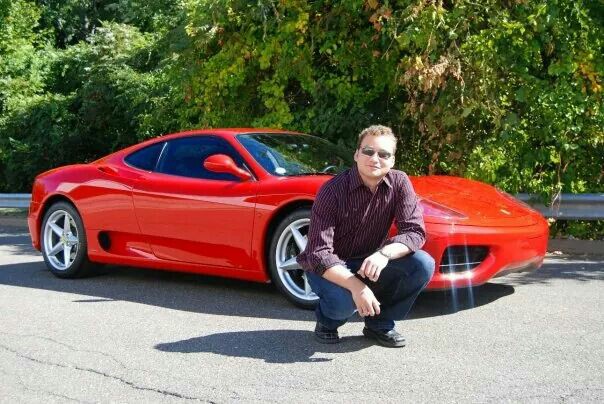

Garza shows off his wealth.

Rural Vermont residents relying on a wireless Internet provider experiencing service problems appear to be collateral damage after a series of scandals and criminal investigations may have prompted the alleged owner to flee to a middle eastern country with no extradition treaty with the United States.

Houston native Homero Josh Garza, 30, had his hands in as many as a dozen business ventures in Vermont, Delaware, and Massachusetts, including Brattleboro’s Great Auk Wireless. But the wireless ISP founded in 2004 apparently is no longer high on Garza’s list of priorities after the entrepreneur discovered the prospect of big profits mining Bitcoins.

GAW’s 1,000 wireless customers are trying to maintain their Internet service, which is experiencing a growing number of service failures. Recently, customers began having trouble sending and receiving email, with nobody answering a support line to help. Last week, the company’s website appeared to be down for several days. Vermont officials considered it another example of why they believe GAW has proven itself a subpar provider with troublesome service.

That could be worrisome in underserved areas like western Massachusetts, where wireless ISPs like GAW have been promoted as less costly alternatives to fiber to the home service. In 2012, Garza gave up on building broadband access in Ashland, Mass., despite being offered a $40,000 government broadband grant, according to the Christian Science Monitor.

Platterpus Records proprietor Dave Witthaus suggests residents and businesses might want to think twice about firms like GAW. Witthaus told Coindesk businesses dependent on the wireless service provider encountered “routine issues with connectivity and customer service.” He told the online publication some businesses switched providers after a two week phone outage in February.

“They could have done well in this area but the customer service has just been awful,” Witthaus said. “And now, two weeks without phone is just unacceptable.”

Is GAW Wireless operating on autopilot?

Garza’s performance in the Bitcoin world has been given similar reviews after his mining venture rose to prominence and then collapsed, leaving investors and regulators looking for answers.

Bitcoin, a digital currency, is not issued by any central banking authority. Instead, new coins are issued to those running complex software that verifies the alternative currency’s public ledger of earlier transactions. The process protects the virtual currency from tampering or other illicit acts like re-spending by its original owner. In return for volunteering computer time to help support the security of the Bitcoin, the software pays users transaction fees and a subsidy of newly minted coins.

The prospect of getting “free money” just by running software encouraged the start of a virtual Gold Rush. Instead of mining in the ground looking for precious metals, prospectors eventually sought investors to fund powerful computers dedicated entirely to “mining” for Bitcoins. The Bitcoin system only releases so many coins at a time, and that number has been dwindling by design and will eventually reach zero. As a result, individual enthusiasts running the Bitcoin software during their spare time have seen their awards deteriorate as large-scale “mining operations” capture a growing percentage of the newly issued currency. To combat this trend, mining pools share resources to compete with the larger players and private contractors sell individuals and clubs time and access on powerful computers in return for a “mining contract.”

Enter GAW, which stands for “Geniuses At Work.” Garza’s business depended on a steady stream of clients investing in his enormous mining operation. GAW Miners claimed it has 200,000 customers and $120 million in revenue in just six months. GAW also reportedly collected 28,000 Bitcoins worth over $10 million in just two months.

Enter GAW, which stands for “Geniuses At Work.” Garza’s business depended on a steady stream of clients investing in his enormous mining operation. GAW Miners claimed it has 200,000 customers and $120 million in revenue in just six months. GAW also reportedly collected 28,000 Bitcoins worth over $10 million in just two months.

Garza was never modest showing off his success, appearing in a tuxedo flying around in a private jet, showing off a collection of expensive Ferraris, and living in a $600,000 5,300-square foot stone house outside of Springfield, Mass.

But even as Garza’s company began moving hundreds of “mining rigs” (high-powered computers) into its newly leased 150,000-square foot warehouse in Park Purvis, Miss., some disgruntled ex-clients and investors began complaining Garza’s record was heavy on promises and light on delivery. Bitcoin news sites also began expressing concern about Garza’s operation. At around the same time back in Vermont, Great Auk Wireless customers experienced a very serious service outage that disrupted their phone and Internet service. While the rumor mill swirled about Garza’s ethics, the Mississippi Power Company was investing hundreds of thousands of its dollars to upgrade power to Garza’s warehouse. In return, GAW committed to stay for at least one year. It left after just a few months, folding operations and leaving the utility with $220,000 in unpaid electric bills and over $73,000 in damages and costs. The utility sued and was ignored by GAW.

“Mississippi Power filed a motion for default judgment because GAW failed to answer or otherwise defend the lawsuit,” the power company said in a statement. “We are asking the court to give us a final judgment on the amount that’s owed on this account.”

GAW Miners’ data center in Mississippi.

Collecting any judgment may prove difficult because most of GAW’s employees and management have reportedly fled, resigned, or been terminated.

With GAW Miners largely defunct, the Securities and Exchange Commission has taken an interest, questioning whether Garza’s ventures involved unregulated securities, a big no-no with the feds. The SEC is also sharing its wealth of information with the Federal Trade Commission, which is investigating GAW Miners for potential false advertising. The Department of Homeland Security also wants to know if Garza was engaged in money laundering, and the IRS is pondering whether Garza reported all of his capital gains for tax purposes.

To get these answers, Garza’s firm was subpoenaed in February to turn over relevant documents. As of late May, Bitcoin traders suspect Garza has left the country and federal investigators behind and relocated to Dubai, in the United Arab Emirates, which has no extradition treaty with the U.S.

Taxpayers may also be victims.

GAW Wireless collected $18,018 in state grant money to expand wireless broadband service in 2014. The company never delivered the service, according to Vermont officials. A Maidstone couple also alleges GAW never paid them the $3,000 they agreed upon for leasing property in East Maidstone. Guy and Gail Giampaolo were to receive free Internet service and a $300 annual payment in return for the lease agreement. They reportedly received neither.

The VTDigger reported several other instances of service problems from the wireless venture in a detailed article published earlier this month. Even the state Attorney General has been unable to contact the company after an earlier letter was returned by the post office with no forwarding address. The Department of Public Service is asking customers who use GAW Wireless to call the Consumer Affairs Line at 1-800-622-4496. The department will provide customers with information about alternative wireless Internet service providers.

Subscribe

Subscribe