The House Energy and Commerce Subcommittee on Communications and Technology has approved a draft bill that could effectively render current CableCARD technology obsolete by allowing cable operators to encrypt channels and introduce new security measures that only work with the cable company’s set-top box.

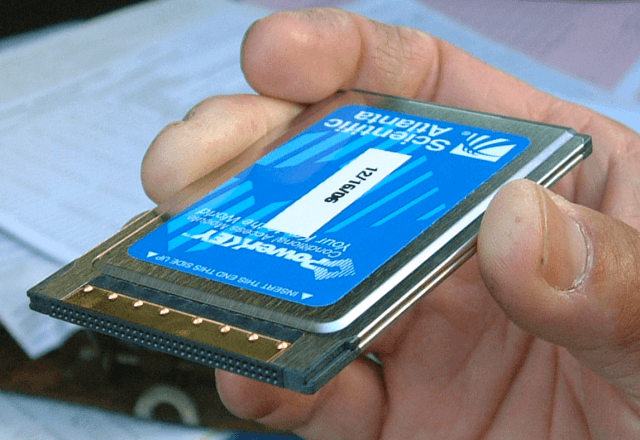

If you look closely inside your cable set-top box, chances are good a CableCARD similar to this is installed inside. But perhaps not for long.

With strong support from the cable industry, the House Subcommittee approved the reauthorization of the Satellite Television Extension and Localism Act (STELA) with language that would end the Federal Communications Commission’s ban on built-in descrambler set-top box equipment unavailable to competitors.

Section 629 of the 1996 Telecommunications Act requires that consumers have adequate access to alternative equipment to view multichannel video programming. In 2003, the FCC adopted the cable industry-developed CableCARD standard that would let customers view encrypted channels without leasing a traditional set-top cable box.

In fact, if you own a cable set-top box manufactured after 2007, chances are you already have a CableCARD without realizing it. It is built-in to your set-top box and decrypts and authorizes your cable television lineup. The cable industry never saw any need to incorporate CableCARDs into set-top equipment because it was designed to handle those functions without needing the extra card. But the FCC’s “integration ban” has insisted cable companies use the CableCARD with hopes it would stimulate universal support of the technology and help facilitate a breakup of the leased set-top box monopoly.

The cable industry has itself largely to blame for the FCC’s actions. Prior to 1992, some cable operators were notorious for saddling customers with expensive set-top boxes that were large and unwieldy. Cable companies regularly raised the rental price of the mandatory equipment in rate increase maneuvers and charged huge penalties when boxes were lost, stolen, or damaged.

Many cable customers never wanted the boxes, preferring “cable-ready” service, which let the television sort out the television lineup without any extra equipment.

But “Cable-ready” televisions were an impediment to the revenue-enhancing possibilities offered by digital cable television that became common in the 1990s. Existing television sets could not receive the digital channels without a set-top box and many customers avoided upgrading service because of the extra costs and equipment requirements. In other areas, signal theft pushed the industry towards encrypting more than just a few premium movie channels. In high theft areas like New York City, cable operators won permission to scramble most, if not all the cable television lineup. Customers needed boxes to receive those encrypted channels.

As early as January 2005, the National Cable & Telecommunications Association told the FCC that independent alternatives like the CableCARD were in direct “conflict with cable’s own market imperatives,” adding there was no economic incentive to support third-party equipment and adopting it would result in increased cable bills.

Powell

Now that CableCARD technology is with us, most cable companies rarely mention it unless customers directly ask. Even CableLabs, the industry engineering group that develops and markets a variety of cable industry technology, has also avoided the subject.

Without any significant backing from the cable industry, most customers never realized they had another option when the cable technician arrived with a leased set-top box in hand. Television manufacturers dropped support for the little-known technology as well.

Cable industry advancements like on-demand viewing don’t work with the standalone CableCARD, creating a disadvantage that further hurt the technology’s chances.

The cable industry argues times have changed and consumers don’t generally want CableCARDs.

NCTA president Michael Powell told Congress that more than 45 million CableCARD-enabled set-top devices are now sitting in customer homes, but only 600,000 of them were requested by cable customers for use in third-party devices. Powell argues supporting CableCARD technology means customers with a leased box are paying for redundant technology. One large cable operator claimed the average set-top box now costs an extra $40-50 to support CableCARD technology.

“Additionally, based on EPA figures, cable subscribers collectively foot the bill for roughly 500 million kilowatt hours consumed by CableCARDs each year,” said Powell. “By all measures, the costs of this misguided rule clearly outweigh its benefits.”

In the end the subcommittee agreed to a compromise by eliminating the “integration ban” that effectively keeps cable companies from switching on new security technology that might not work with CableCARDs but also gives the FCC the authority to create or authorize new independent set-top box technology ‘when needed.’

This means either the cable industry could develop a next generation of CableCARDs that work with advanced security measures or more likely the ongoing advancement of IP-delivery of television programming could make the matter moot. As the cable industry moves towards online streaming of cable channels, various third-party devices like Roku could be used to access much of the cable lineup without worrying about a CableCARD. Recording such programming for later viewing will likely require agreements with copyright-obsessed programmers, the cable industry, and manufacturers, however.

Subscribe

Subscribe