Now that the initial shock of an aggressive — some say “audacious” — move by the Justice Department to block a merger AT&T confidently called “a done deal” is past, analysts of all kinds are attempting to discern the inside reasons for the merger’s rejection, where the deal can go from here, and what signals this will send the rest of America’s telecom industry.

In short — was this one merger proposal too far over the line?

The Justice Department reviewed reams of data, document-dumped by AT&T, on the company’s rationale for wanting to absorb T-Mobile and its implications for employees, consumers, and the dwindling number of wireless competitors.

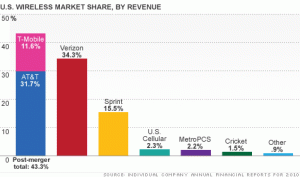

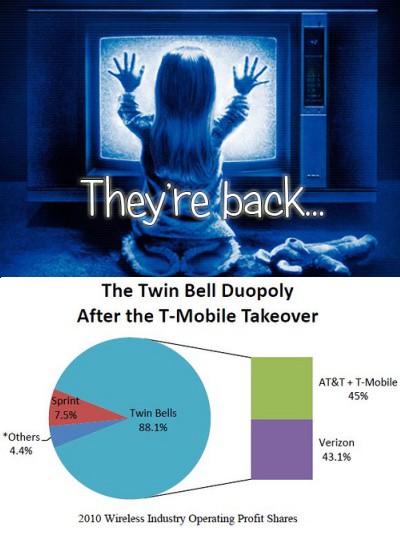

They quickly discovered they did not like what they were seeing: an all-new AT&T with a combined 132 million wireless customers, completely dwarfing all of their competitors and signaling a full-scale retreat from the company’s historic landline network. An unregulated, increasingly concentrated wireless marketplace, represents the Wild West of fat profits, ripe for the picking by those large enough to control the market. Increasingly, that means two former Baby Bells — AT&T and Verizon.

The Wall Street Journal charted more than two decades of mergers and acquisitions, which reduced nearly two dozen players down to five supersized telecom companies.

The Politics

Decisions at Justice are hardly made in a vacuum. Politics always plays a role, and it’s a safe bet Obama Administration officials well-above rank-and-file lawyers in the Antitrust Division sent clear signals to the Department about how it wanted the review handled. After all, this same team of lawyers had almost no trouble approving a mega-merger between NBC-Universal and Comcast Corporation, not finding anything ‘antitrust’ about that deal. But Justice officials hurried out their own lawsuit with a wide-ranging, harsh condemnation of the deal at yesterday’s press conference. As most Americans already know, competition in the cable industry is hardly robust, but market concentrating mergers and acquisitions are approved regularly in that industry. So why did the Justice Department have such a problem with AT&T?

America's Wireless Market: Beyond well-behind, third-place Sprint, no other carrier comes close to AT&T or Verizon Wireless.

Many analysts seem to blame the company’s “arrogance” in telling reporters the merger was a breeze to be approved, others point to spectrum issues, as well as complaints about AT&T’s poor service potentially ensnaring T-Mobile customers. But above all, Justice lawyers believe that America’s wireless marketplace needs at least four national wireless carriers, particularly scrappy T-Mobile, which has a long history of being a disruptive player in the market, loathe to offer the kind of “identical twin”-pricing common at AT&T and Verizon Wireless. Losing T-Mobile’s aggressive performance in the market would mean declaring open season for price increases and abusive business practices. After all, where would wireless consumers go?

That “four national carrier”-test could be a big problem for T-Mobile, as it could mean Justice lawyers would also reject an presumed alternative — combining Sprint and T-Mobile, rumored before AT&T moved in and stole the show. A new entrant willing to buy-out Deutsche Telekom’s U.S. wireless interests may be the only palatable solution acceptable to Justice lawyers because it would keep T-Mobile intact and running, independent of other wireless carriers.

Justice also completely discounted the relevance of regional carriers like MetroPCS, Cricket, U.S. Cellular, and other smaller providers. The reason is simple: roaming. All of these smaller providers are completely dependent on the four large national carriers to deliver essential roaming services for their customers who travel outside of the regions where these smaller companies deliver service themselves. All national carriers would have to do to control an overly-competitive “problem” carrier is withdraw roaming agreements or raise prices for them.

Sprint, among others, is obviously the most relieved by yesterday’s events. Their long term viability as a national carrier dwarfed by AT&T and Verizon Wireless would have raised numerous questions about whether that company could survive in the long term. Sprint would have also felt pressure to beef up its own operations, likely through acquisitions of several regional carriers, particularly MetroPCS and Cricket, which share its CDMA network standard.

Wall Street is livid, of course.

The great gnashing of teeth has begun on Wall Street, evident as stock analysts begin raising questions about President Obama’s “anti-business” policies. While executives at both AT&T and T-Mobile are at risk of losing substantial bonuses for pulling the deal off (and providing special retention packages to keep key talent from leaving), there is also a lot of money to be lost in New York and Washington should the deal collapse. Take the “little people” that will be out tens of millions in deal fees and proceeds from extending credit, implementing the merger itself, and structuring the legal mechanics. They include:

The great gnashing of teeth has begun on Wall Street, evident as stock analysts begin raising questions about President Obama’s “anti-business” policies. While executives at both AT&T and T-Mobile are at risk of losing substantial bonuses for pulling the deal off (and providing special retention packages to keep key talent from leaving), there is also a lot of money to be lost in New York and Washington should the deal collapse. Take the “little people” that will be out tens of millions in deal fees and proceeds from extending credit, implementing the merger itself, and structuring the legal mechanics. They include:

Arnold & Porter: The now infamous law firm that accidentally posted an un-redacted document on the Federal Communications Commission website that exposed, in AT&T’s own words, what consumer groups already strongly suspected: AT&T preferred the long term benefits of knocking pesky T-Mobile out of the marketplace, even though the $39 billion dollar price tag dwarfed the $4 billion estimated cost of building AT&T’s own 4G LTE network. That’s the 4G network executives deemed “too expensive” earlier this year. With a deal collapse, the firm can say goodbye to lucrative legal fees and perhaps more importantly, their reputation of properly managing their clients’ business affairs.

Greenhill & Co.: Greenhill is one of several all-star, platinum-priced advisory firms hired by companies acquiring other companies to structure and implement their mergers. With Greenhill hoping for a substantial piece of at least $150 million set aside by AT&T to cover these specific costs, a merger-interrupted could cost key people some nice year-end bonuses.

JPMorgan (Chase): The House of J.P. Morgan handed over a check for AT&T worth up to $20 billion to help finance the deal. JPMorgan doesn’t do that for free. In addition to any interest proceeds, JPMorgan also charges a range of underwriting and administrative fees that could easily total $85 million dollars. AT&T might have to send the check back.

Cable Business News & Business Media: One of the most ironic developments watching the Justice Dept. decision unfold was the unintentional amount of AT&T advertising promoting the merger that preceded video reports and appeared adjacent to AT&T-related stories. Those ads may soon end, costing cable news and the business press substantial ad revenue.

Cable business news networks offered up scathing analyses. Among anchors and analysts upset with the news of the merger’s potential derailment, it didn’t take long for “couched questions” to begin, pondering whether President Obama was against big companies, jobs, or the concept of the private sector in general. Completely missing: coverage of the benefits for consumers who potentially don’t have to endure a further concentration in the wireless marketplace.

Craig Moffett from Sanford Bernstein, who usually celebrates all-things-cable, today told the Wall Street Journal the actions at Justice will harm business at every U.S. wireless carrier.

“Put simply, the industry will be structurally less attractive than it would otherwise have been,” he said. “Pricing is likely to be less stable, and profound technological risks, including free texting and bandwidth arbitrage, that would be manageable in the context of a significantly consolidated industry now become much more threatening.”

In other words, a hegemony of AT&T and Verizon Wireless could play rough with third party developers trying to undercut text message pricing and deliver data plan workarounds. With more competitors, consumers could simply abandon abusive providers. Without those competitors, consumers have to pay AT&T’s asking price or go without service.

The Law

AT&T may be hoping it scored one potential success in its anticipated legal challenge against the Justice Department’s antitrust case.

The judge assigned to hear arguments is Ellen Segal Huvelle, who has a track record of slapping down government overreach. Huvelle previously rejected Justice Department objections to the merger of SunGard and Comdisco — two disaster-recovery businesses. The government argued the merger would leave just two major players in that business. Judge Huvelle dismissed that, claiming the government too-narrowly defined what a disaster-recovery business entailed. If she finds AT&T’s arguments of robust competition from regional carriers, landlines, and Voice Over IP credible, Justice lawyers may have a problem. So could consumers.

[flv width=”512″ height=”308″]http://www.phillipdampier.com/video/PBS Audacious Move to Block Merger 8-31-11.flv[/flv]

PBS Newshour explores where the AT&T/T-Mobile merger goes next, now that the Justice Dept. sued to stop it on antitrust grounds. (7 minutes)

Subscribe

Subscribe