The year 2013 marked a significant turning point for phone companies that have handled voice telephone calls for over 100 years. For the first time, the volume of domestic telephone calls and the revenue generated from them was nearly flat. For the last two years, both are now in decline on the wireless side of the business as North Americans increasingly stop talking on the phone and text and message instead.

The year 2013 marked a significant turning point for phone companies that have handled voice telephone calls for over 100 years. For the first time, the volume of domestic telephone calls and the revenue generated from them was nearly flat. For the last two years, both are now in decline on the wireless side of the business as North Americans increasingly stop talking on the phone and text and message instead.

The U.S. wireline business peaked in the year 2000 with 192 million residential and office landlines. Over the next ten years, close to 80 million of those — 40 percent, would be permanently disconnected, replaced either by cell phones, cable telephone service, or a Voice over IP line. Wireless companies picked up the largest percentage of landline refugees, most never looking back.

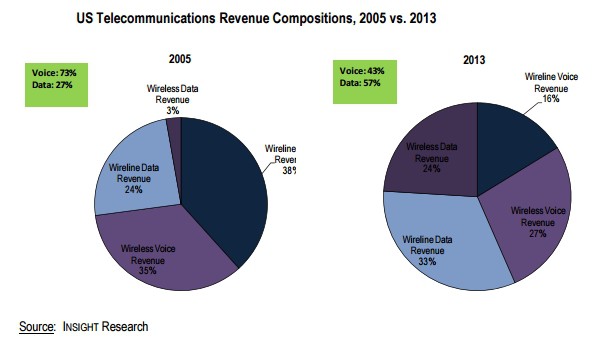

Over one-third of more than $500 billion in annual revenue generated by telecom companies in 2013 came from voice services. Although that sounds like a lot, it’s a pittance of a percentage when compared to 2005 when AT&T, Sprint, T-Mobile, and Verizon Wireless earned most of their revenue from voice calls. Ten years ago, wireless companies principally sold plans based on the number of calling minutes included, and many customers often guessed wrong, paying per minute for calls exceeding their allowance.

At first, this represented a revenue bonanza for the wireless industry, which earned billions selling customers minute-based calling plans that came with built-in cost-controlling deterrents for long-winded talkers — the concern of using up their calling allowance.

Starting in 2008, wireless industry executives noticed something peculiar. While revenue from texting add-on plans was surging, the growth in calling began to level off. Wireless voice usage per subscriber peaked at an average of 769 minutes in 2007 and began falling after that year. By 2011, the average customer was making 615 minutes of calls a month. As customers began downgrading calling plans, wireless carriers shifted their quest for revenue towards text messaging.

Starting in 2008, wireless industry executives noticed something peculiar. While revenue from texting add-on plans was surging, the growth in calling began to level off. Wireless voice usage per subscriber peaked at an average of 769 minutes in 2007 and began falling after that year. By 2011, the average customer was making 615 minutes of calls a month. As customers began downgrading calling plans, wireless carriers shifted their quest for revenue towards text messaging.

For awhile, texting earned wireless companies astounding profits that required little extra investment in their networks. SMS service at most carriers was effectively priced at $1,250 per megabyte, broken up into 160 byte single messages. In 2011, over 2.3 trillion text messages were exchanged. A message that cost a wireless carrier an infinitesimal fraction of a penny to send and receive cost consumers up to 20 cents or more apiece if they lacked an optional texting plan. To further boost revenue, some carriers like Verizon Wireless began to pull back offering customers a variety of tiered texting plans with different messaging allowances, switching instead to a single, more expensive unlimited texting plan. Many customers balked at the $19.95 a month price and began exploring other forms of messaging each other.

The industry’s demand for profit eventually threatened to kill the goose that laid the golden egg. At the same time wireless carriers were raising prices on text messages and forcing customers into expensive texting add-on plans, free third-party messaging apps began eating into texting volume. By 2012, the use of SMS declined for the first time, with 2.19 trillion text messages sent and received, down 4.9 percent from a year earlier.

The industry’s demand for profit eventually threatened to kill the goose that laid the golden egg. At the same time wireless carriers were raising prices on text messages and forcing customers into expensive texting add-on plans, free third-party messaging apps began eating into texting volume. By 2012, the use of SMS declined for the first time, with 2.19 trillion text messages sent and received, down 4.9 percent from a year earlier.

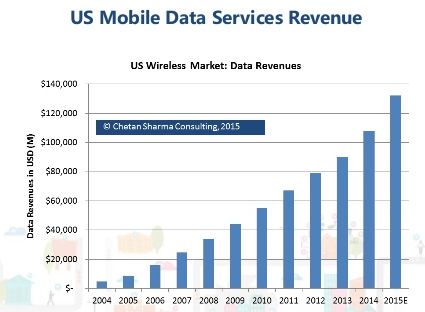

It took little time for the wireless industry to realize the days of offering plans based on calling minutes and texting were quickly coming to an end. Younger users began the cultural trend of talking less, texting more — but using a growing number of free alternative apps to do so. As a result, both AT&T and Verizon shifted their plans away from focusing on revenue from calling and texting and instead moved to monetize data usage. Today, both carriers offer base plans featuring unlimited voice calling and texting almost as an afterthought. The real money is now made from selling packages of wireless data.

Wi-Fi calling allows customers to make and receive voice calls over a Wi-Fi connection, not a nearby cell tower. The prospect of bundling that option into a cell phone just a few years ago would have been unlikely at some providers, unthinkable at others. It was never considered a high priority at any traditional carrier, although T-Mobile began offering the service all the way back in 2007.

Since most calling plans now bundle unlimited calling, letting calls ride off the traditional cellular network is no longer much of an economic concern.

Some even expect carriers to eventually embrace Wi-Fi calling, declaring it superior to alternatives like Hangouts and Skype, which require an app to handle the call. A Wi-Fi call can be received by anyone with a phone.

Some even expect carriers to eventually embrace Wi-Fi calling, declaring it superior to alternatives like Hangouts and Skype, which require an app to handle the call. A Wi-Fi call can be received by anyone with a phone.

This month, the last holdout, Verizon Wireless, capitulated and announced it had won approval from the FCC to introduce Wi-Fi calling to customers, joining Sprint, T-Mobile, and AT&T. But Verizon plans to initially limit that service, offering an app that must be installed to make and receive Wi-Fi calls. The other three carriers integrate Wi-Fi calling directly into the primary phone call app already on the phone.

The introduction of the service is unlikely to have a significant economic impact on any wireless carrier. Most have ample room on their networks to handle cell call volumes. Whether a call is placed over Wi-Fi or traditional cellular service, it will ultimately end up on the same or a similar IP-based phone switch as it makes its way to the called party.

With little revenue-generating opportunities for voice calling or SMS messaging, companies have nearly stopped the practice of monetizing individual telephone calls, preferring to offer unlimited, all-you-want calling and texting plans that used to cost consumers considerable amounts of money.

Now wireless carriers see fortunes to be made slicing up and packaging gigabytes of wireless data, sold at prices that have little relation to actual cost, just as carriers managed with text messaging for the last 20 years. A Verizon Wireless customer using 12GB of data in October that kept a now-grandfathered unlimited data plan paid just under $30 for that usage. (This month Verizon raised the price of that coveted unlimited plan by $20 a month.) Verizon charges $80 for that same amount of data on its new “XL” data plan. Verizon’s cost to deliver that data to customers is lower than it was five years ago, but customers wouldn’t know it based on their bill. As always with the wireless industry, costs often have no relationship to the price ultimately charged consumers.

Subscribe

Subscribe